Community reviews wildfire contamination of air, soil, and water

6 min read

One year after the 2020 Labor Day fires, community members reviewed the contaminants left in the air, soil, and water after a wildfire.

Wildfire can create hazardous waste-level contamination, in the soil, air, and water. Purdue University’s Andrew Whelton.

[00:00:09] Andrew Whelton: When people rely on private wells, the fire can come through and damage these wells and the plumbing and the pipes that are on that property. And you get towards larger communities, you have water delivered through buried pipes and these pipes, then deliver it to homes or commercial buildings or schools. Fire damages these systems pretty much the same. Many of the same materials that are used for homes that have wells are used for homes that have water coming from a utility or some type of water system.

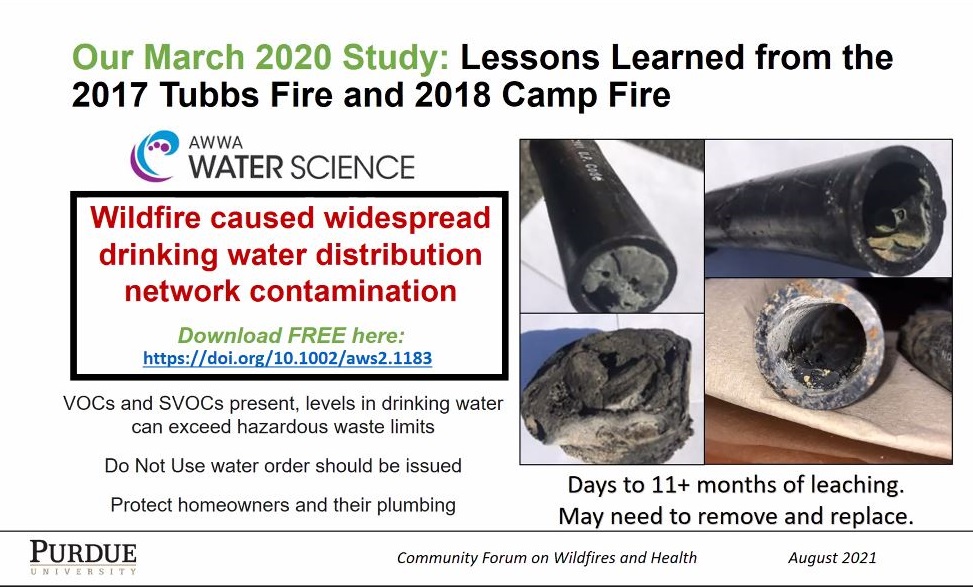

[00:00:47] John Q: The problem was first seen after mega-fires in California.

[00:00:51] Andrew Whelton: Now after the fires in 2017, the City of Santa Rosa discovered hazardous waste-scale contamination in the City of Santa Rosa’s water system, being delivered to homes that were still standing. They looked at chemicals called VOCs, volatile organic compounds that don’t like to be in water, and SVOCs, semi-volatile organic compounds. They’re heavier and hang around in water a little longer. These compounds include benzene, styrene, and they are generated when you’re basically cooking or burning plastic.

That’s one of the lessons that was learned in 2017: After wildfires, you do not want people to boil their water because boiling water would strip out the chemicals from that water and put them into the air.

Thank you for supporting

local citizen journalism

And, two years later, the Camp Fire occurred in California. And that again, precipitated hazardous waste-level contamination of drinking water systems in multiple systems, not just one.

And so my team here at Purdue tried to figure out exactly where is it coming from, because many people really hadn’t thought about it before. So we went in and we did testing. We also worked with the community, which was how we were able to really help a lot of people, and then we came back to Purdue in Indiana and we tested plastics.

If you heat up plastics, the pipes that are in the ground or at the water meters or in the buildings, they actually can generate contamination that’s not there if you just put, like tap water through it. And then that can cause hazardous waste level contamination.

[00:02:38] John Q: The water system can also be contaminated by smoke.

[00:02:42] Andrew Whelton: When you have a fire in a town or a building, you’ll have a water break and all the water on one side of the house rushes to the other. And if there’s a pipe like a faucet that’s open, it will suck all that smoke into the pipe and then drag it down through the pipe. And so that’s another reason sometimes why people can have contamination in their plumbing.

[00:03:07] John Q: Chris Ryan described contaminants in the soil and air.

[00:03:11] Chris Ryan: My name is Chris Ryan. One of the major concerns for most residential house fires are the materials that burned during the fire. Those materials range from plastics, metals, paint, solvents, fuels, carpeting, roofing tar, and asbestos and lead uh, the offgassing of those materials are called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAHs, and they have an effect and can be found in areas of wildfire and house fires.

The Valley’s mobile home parks, the vast majority of these parks and homes were built prior to 2004, and very likely to contain asbestos, lead and other potential toxic materials. The problem that we faced in situations is that any toxic material or byproducts does not stay just on the property, but has the ability to migrate to other properties.

[00:04:08] Lisa Arkin: I’m Lisa Arkin, executive director of Beyond Toxics. In wildfire, smoke contains high levels of these small, dangerous types of particle pollution known as PM 2.5 or 10. These can be specks of toxic soot. These tiny particles can go deep into our lungs. We breathe in the air and this causes inflammation and congestion. It can make us cough. It can make us have trouble breathing. It can lead to onset of asthma or asthma attacks. It can contribute to chronic bronchitis if you’re exposed for a while over time, and can exacerbate conditions like COPD. And over time medical scientists have shown that breathing in polluted small particulate matter can cause lung cancer.

If you’re a pregnant woman, what you’re breathing in can cross into the placenta and the room where a baby is developing and can potentially cause harm to that baby as well. And there’s plenty of medical research showing us that air pollution takes a particular toll on pregnant women and the developing baby; can increase the risk of complications during pregnancy; and it can increase the risk of premature birth, low birth weight, and heart defects in babies.

So as our lawmakers, our communities, our environmental agencies get to work on protecting public health from pollution, they really need to stay focused on the health of the people of Oregon. And I think this follows up very well from what Andy and Chris were saying, that in these cleanups, we need to clean up to a degree where we’re protecting health.

[00:06:05] John Q: Chris said some EPA regulations need fine-tuning.

[00:06:09] Chris Ryan: The EPA has inadvertently set a different set of standards for regulating the problem. If you have 50 homes in the mobile home park and 10 of them test positive for hazardous materials, the entire site will be considered contaminated. Now, if you have the same 50 homes in a residential neighborhood and 30 of them test positive, only those 30 would be considered contaminants. What this does is we have pockets of neighborhoods without any air monitoring or any air data being collected even in the areas known to be hazardous.

[00:06:43] John Q: Chris also said we need more long-term health studies.

[00:06:46] Chris Ryan: Libby Montana was famous for having a vermiculite and part of the site contamination of mining vermiculite is, there is some level of asbestos. That asbestos is less than 1%, which is the regulated limit that the EPA has set, leaving the residents of the town to believe that they were perfectly fine and had no danger. But what they found out was that over time, these residents of the town started developing asbestos-related illnesses that were previously only linked to high level exposure. The acute exposure over a long period of time had the same effect as a heavy exposure over a short period of time.

[00:07:30] John Q: They were asked whether it is safe to eat vegetables from a local garden.

[00:07:36] Chris Ryan: It really depends on the level of cleanup that took place. Most contractors, the EPA included, are taking six to eight inches of soil below the top layer. One thing that I learned in this industry is that in some circumstances, the solution to pollution is dilution. That said, if they remove that top layer and with the heavy rain that we’ve had, where we’re coming close to the one-year mark, I would say that you can’t rule it out completely, but that you could say that it’s very, very unlikely to have any issues with that. And again, That would all depend also on what was on the property to begin with. It would definitely be a case to case basis, but for the most part, I think you’d be safe to start your garden back up if you’ve had a good cleanup done on the property.

[00:08:23] John Q: The session was organized by Beyond Toxics and Unite Oregon.

[00:08:29] Erika Bucio: We Unite Oregon have our main office in Portland and we also have four different chapters, one in the Rogue Valley, which is where I’m at. Unite Oregon is actually led by people of color, immigrants and refugees, rural communities, and people experiencing poverty. We work across Unite Oregon to be to unified in a cultural movement for social, economic, and racial justice.

[00:08:53] John Q: Andrew praised the local groups for their organizing work.

[00:08:57] Andrew Whelton: Communities that organize and work with one another to help one another are the ones that I see being successful at recovering from these disasters. To figure out, how do we rebuild our community? How do we rebuild better so that we’re not equally vulnerable.