FUSEE sees promise in fire mosaics

5 min read

Fire is the best way to remove surface fuels that contribute to today's gigafires. FUSEE is encouraging development of mosaics.

FUSEE, Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology, called for mosaics and more use of fire to reduce dead and downed surface fuels. FUSEE Executive Director Tim Ingalsbee.

[00:00:12] Tim Ingalsbee: Big fires are going to be part of our future because of climate change, but big fire areas can be comprised of a mosaic pattern of different fire ages or fire severities and intensities. And that’s a really good thing.

[00:00:28] Mosaics are really an asset to fire crews. Each fire, the mosaic that it leaves, or that could be cultivated by active management, is a potential asset to the next fire, a means for protecting rural communities, at the same time, restoring the ecosystem with this kind of fire mosaic patterns.

Thank you for supporting

local civic journalism

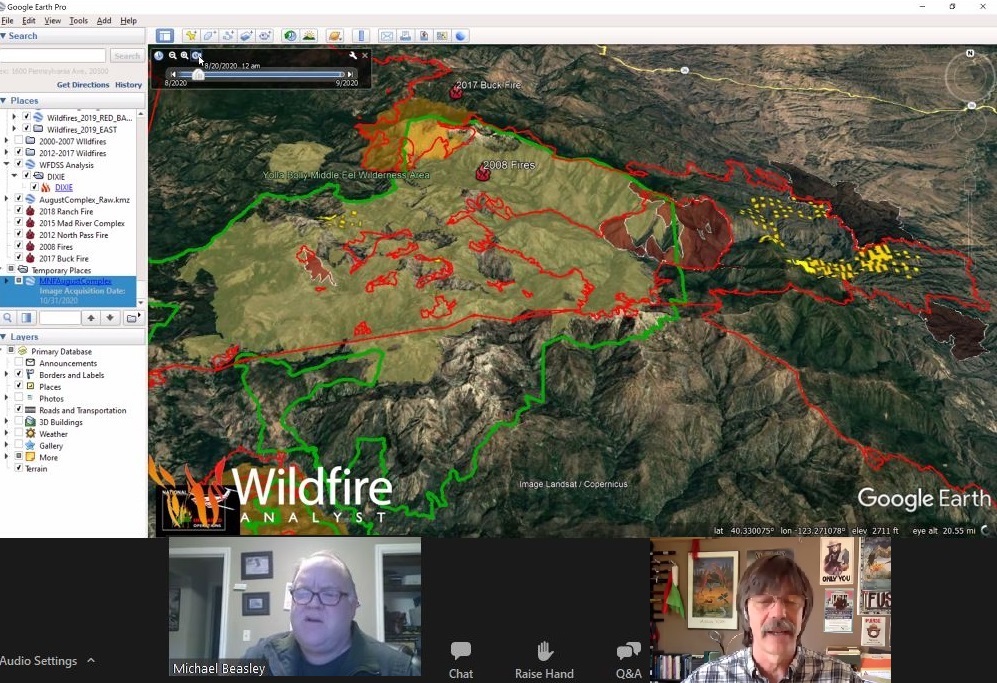

[00:00:50] John Q: FUSEE founding board member and fire behavior analyst, Mike Beasley.

[00:00:55] Mike Beasley: We’re talking about protecting communities with an emerging, healthy mosaic of fires across a landscape.

[00:01:04] There’s two kinds of forest fuels. There’s standing live fuels, and then we have surface fuels, the dead and the downed fuels.

[00:01:11] We’re not going to talk about the standing live fuels at all. When we talk about tree harvest, that’s what a lot of folks offer as a solution to the wildland fire problem. But we’re going to talk about the surface fuels instead. Essentially those surface feels contribute significantly more to the rate of spread and severity of wildfires than the standing live trees.

[00:01:34] Those surface fuels, everything from needle cast to twigs to branches, tree boles stacked on the ground or on top of each other, and even subsurface fuels like duff, these fuels have to do one of two things in nature. They have to either decompose or they have to be consumed by a wildfire.

[00:01:51] Otherwise they accumulate and that accumulation is measured in tons per acre. And as you can imagine, in dry forest types, especially Ponderosa pine all across the American West, that fuel accumulation can be a real problem.

[00:02:06] In a functional fire regime, where you have regular lightning or anthropogenic fire, you would have quite a bit smaller and less severe fires, generally, as the, as subsequent fire perimeters overlap. The fuels are reduced over time. Generally that just gets cleaned up, and after you get into a cycle of resembling the natural cycle, which was as short as every 10 years for some of these dry pine forests, you see those surface fuel numbers really stabilized at a much lower level, and we can see that through tree ring records, that the fires were generally of a smaller size.

[00:02:45] Fire perimeters start to fit together like jigsaw pieces, and you get a very diverse landscape as a result of all those overlapping fire perimeters. You can see that with a lot of edge effect, a lot of heterogeneity in the landscape. Generally we let those perimeters interact naturally and the fires did become self-limiting and subsequent fires had less smoke emissions and less severity.

[00:03:14] But you can really see that nature is trying to re-establish these mosaics of fire out on the landscape and they are self-limiting at least to a certain extent.

[00:03:24] So that has a lot of implications. Narrow, linear fuel breaks may make evacuation routes safer, but are ineffective in slowing or stopping these fires at the peak of the burn period, in the middle of fire season, when you might have spotting distances in excess of three to five miles. But they’re most effective for use as controlled lines for planned prescribed fire in the fall or the spring. Every fire out here on the landscape is an opportunity to anchor your line for containment of a subsequent fire. So you are counter-intuitively needing to actually put more fire into the system rather than less fire.

[00:04:04] Tim Ingalsbee: In future wildfires, we might want to think of, ‘Hey, this is an opportunity to manage the fire to create a nice little patch, a little mosaic, especially in these remote uninhabited areas or even fires entering existing wilderness areas.’

[00:04:20] You don’t need to send armies of firefighters that are trying to do perimeter control in these remote areas; that’s spreading the crews way too thin, scattering them across the landscape. You can rest assured the fire’s going to be okay in that area. We can concentrate our resources near the towns and communities that really need us.

[00:04:38] So that’s a couple ways to look at these is incorporating fire mosaics, not just in suppression operations, but also in land stewardship.

[00:04:49] John Q: Tim was asked whether it might be difficult to get public support.

[00:04:53] Reporter #1: Just one thought Tim, but with all due respect, there are times where prescribed fires that seemed to be in places that were totally remote, have gone out of control and done damage. You know, there’ve been some really tragic incidents, not a lot, but enough that it makes it harder.

[00:05:10] Tim Ingalsbee: Points are well-taken that it’s all about risk and managing risks, but taking opportunities where you can to re-knit the landscape with fire mosaics, employing fire where we can, is the best, really, the best fuels treatment method for talking about big fires on the landscape. Fire does a great job of recycling dead needle mats. So that’s what we’re talking about really. And it is working from the ground up, in terms of fuels reduction, instead of the crown down.

[00:05:43] To me, the most flammable tree in the forest is not a big old growth snag. That’s rarely—mostly inflammable. The most flammable tree in the forest is a young conifer, densely stocked in a tree farm or timber plantation where the most flammable part of a tree, its needle mass, is right there on the ground, close to any kind of spark or surface fire. Inter-threaded crowns, I mean, that’s just one contiguous, massive, highly flammable fuel, lots of oxygen to feed the flames. And so that to me is the most flammable tree age and type of structure is that conifer tree farm. And we’ve got to figure out how to manage for that because they are not really sustainable given climate change is increasing the frequency of wildfire events.

[00:06:34] Reporter #2: The Beachie Creek Fire started by lightning in a wilderness area three weeks before the 2020 wind event. Many Detroit residents blamed the Forest Service. Will this public perception limit our ability to use ecological fires?

[00:06:50] Tim Ingalsbee: We’ll have to get past that misperception of the Beachie Creek Fire was Forest Service negligence. It just was a harsh lesson in our human limits to control this very powerful force of nature in this altered climate that we’ve caused. It may take some effort to get comfortable with working with fire on the landscape and reconstructing a landscape mosaic as opposed to just, ‘Hit it hard and put it all out quick, if possible.’ But what we’re finding out with climate change, that’s not possible. So we’re pitching a kind of new strategy for active ecological fire management, incorporating this concept of fire mosaics.

[00:07:32] John Q: FUSEE says fire can be used to reduce surface fuels, so that the next fire is smaller.