Native son Will Kramer to city: More phone chargers, less brute squad

8 min read

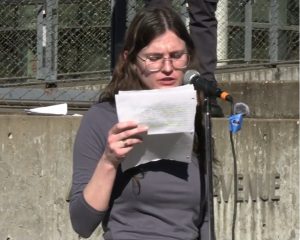

Stories from the streets, as Sarah Koski visits with native son William Scott Kramer.

Will Kramer: Yeah, I grew up, born in ‘67 in the affluent South Hills up above 40th and Donald, that hidden wonderful community up there, that a lot of Eugene doesn’t know about to this day. I was born right into the Breeden Brothers frenzy of building out the South Hills.

[00:00:30] I’ve got a long history in this city. And my father was in with Archie Weinstein back in the day, County Commissioner Otto t’Hooft, Jerry Rust. And so I grew up from the age of six in the political scene here.

[00:00:47] I learned to flip the bird from my father when I was seven years old because Bob Packwood was driving behind our car, headed up to the Hoedad Ranch to have a county commissioner meeting. And I remember him getting out and saying, “Well, William, did your dad teach you that?” Yes. (Laughing)

[00:01:09] And so I went to Edgewood Elementary and Spencer Butte Junior High, which were just amazing schools to go to.

[00:01:21] When I was 10 years old and 15 years old, my route manager—and I was one of her two favorite paper route guys, because we teamed up and got more routes—Bridget Wood.

[00:01:34] And teachers like Jerry Andrews, the phys ed teacher, who still had the right to paddle you if you got caught cussing in the locker room or doing something you shouldn’t have done, and that right was given to him by the parents, you know.

[00:01:51] I was a Boy Scout and I was in Troop 316 up there with Ken Higgins who was the president of Smith & Crakes Insurance for years and years and one of the most morally correct men I’ve ever met in my life. He did not say anything he did not live, 100%. And he still teaches me lessons to this day, as does Jerry Andrews.

[00:02:17] And, wow. Then, of course, South Eugene, the Purple Porpoise, Don Jackson, who was quite a swath cut into this community, and he had a huge impact on me. The first day at South, I felt his presence behind me when I was trying to open my locker the first time. And I turned around and here’s this man in a purple suit with a purple sequined cowboy hat, a tie, and purple sequined cowboy boots, standing 6 foot, 5 (inches), and he sticks his hand out and he says, “Don Jackson, principal, South Eugene High.”

And I stuck my hand out timidly, and he shook it once and then he started squeezing and he said, “I understand your name’s William Scott Kramer.” And I said, “Yes, it is.”

[00:03:15] And he said, “Please tell me something, as a tenured administrator in the 4J system, that will make me the happiest man on the planet today.” And he looked at me and he squeezed a little harder and he said, “Tell me you’re the last Kramer child.” And I said, “Yes, I am.” He said, “Excellent, son, we’re going to get along just fine.”

[00:03:40] And our relationship was adversarial at best. And it was one of us stepping in front of the other till the day he came into Elmer’s Restaurant Corp., where I worked as the vice president, director of operations, in order to raise money for the Thanksgiving Day feed down in the Whit. And the CEO and the COO called me on one of their cell phones and sounded like they were in a hurry and said, “There’s a guy coming in, he’s going to want money. Keep it as small as you can, but just, you know, you’re going to have to give him a check and get him out of there, but keep it down if you can.”

[00:04:26] And that’s right when I saw Don Jackson walk in front of my door, going up to the front desk. And I didn’t even get to say “Send him in,” and he opened the door and he stuck his hand out and said, “Don Jackson, formerly principal of South Eugene High School.” And apparently the CEO and the COO were South Eugene graduates as well.

[00:04:48] And, yeah, he told me just fill in the generics and he’d write the zeroes. (Laughing)

[00:04:56] Yeah. I’ve been at the top of both worlds and the bottom of both worlds twice. I have a really unique perspective. You know, I was the guy living in the house up in the South Hills that the police would go by, “Hey, Mr. Kramer, how you doing?”

[00:05:11] And I’m the guy that they, you know, arrested, criminalized, that they beat up three times. And the only difference was my wallet, the size of my wallet. It’s been a brutal awakening. You know, beat down and scared to death, living with sweeps, and police just doing terrible things, and the community doing terrible things.

[00:05:38] And this city tends to, oh, get around things as far as the government’s concerned and a long history with the police being used as a brute squad. All they’ve been doing for decades is just running around with cattle prods and upsetting the nest. So it’s a big game of musical chairs. That’s why new ones land right there. And they keep doing that, and they’ve done nothing except move us around, constantly take our stuff.

[00:06:12] Basically, you know, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had police tell me, “Just leave town.” And I said, “No, you got here last. It’s my town. You leave.” And that’s gotten me beat up three times by groups of police, while handcuffed. And that’s a hard pill to swallow, when I was born here.

[00:06:32] And don’t get me wrong. There’s some good ones. (Eugene Police) Sgt. (Dave) Clark is a good man and therefore a good police officer and he works excellent with the homeless. I appreciate the heck out of him. And there are others, but they’re outnumbered. They’re outnumbered.

[00:06:51] You know, nobody’s…nobody’s looking out for us.

[00:06:55] John Q: He spoke about the importance of phones when you’re homeless. Phones will be stolen just to make one call, to connect with another human being.

[00:07:04] Will Kramer: I think the phones probably became the first thing taken, even before their medicine, even before the drugs, a phone that they need to stay connected, to have a lifeline. It’s a rough life out there, and not just between the homeless. There’s bad people that come out and do bad things to homeless people. And when you’re disconnected, oh, it’s terrible. At one point I went through 21—21 phones, by best count.

[00:07:36] John Q: Let’s pause to consider all the people we love who have struggled with addiction.

[00:07:41] Will Kramer: I was faced with a terrible moment when my daughters said, Dad, we don’t want to talk to you anymore… There was a period of time where my children would not talk to me, and that, that took me right down to considering suicide again. It was devastating. That, and the feeling of disconnect, not having that phone to even reach out… It’s terrible what the isolation does, the need for connection.

[00:08:16] I started that camp on 13th and helped start the one at Washington Jefferson and we were able to do things nobody’s ever done as a group of homeless before. And we gained quite a community backing, both in outreach groups and in donors.

[00:08:38] And just the success we had at that 13th Street camp, by the guys that started it with me going over to the neighbors and shaking hands, say, “Hi, we’re from over there. And we want to know what your concerns are, because here’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to survive and stay put and be safe.”

[00:08:58] I used to go to the apartments and talk to them about the camp across the street, I’d say, “I’m trying to talk to all of your neighbors over here, and you. It would sure help if I had their names. Can you tell me your next-door neighbor’s name? How about on that side? Maybe above or below? Don’t you see that as a problem?”

[00:09:19] You know, people don’t even know their neighbor anymore. We’re a bunch of people living in real close proximity, we are not a community. And how are you going to govern or fix a community if it’s not there?

[00:09:32] Right now we’re standing on two opposite sides, or 15 opposite sides of a canyon. And we’re all scared of being the one over there. Or scared of the one over there. There’s been a big disconnect.

[00:09:47] And, you know, I walk around now having lived here my entire life, having been from a political family, a military family, and not knowing all these new things, I have no clue who put them there, where they came from, what it’s about. It’s terrible. There’s a lot more people here than there used to be and as far as I’m concerned, they broke my city. I allowed it to get broken. So I’m just as much at fault, but it’s ruining our city.

[00:10:20] And you have to remember that you’re dealing with a community—they have been traumatized. They have been ridiculed. You know, I’ve been told, I can’t tell you how many times: The best thing I could do for my community is to gather up my homeless friends and go kill ourselves. And this is my town, you know. It’s, it’s disgusting.

[00:10:44] It’s not my city anymore.

[00:10:47] It was nice to have a curbside view of all this city had to offer over the past 40 years. It’s been fun, but I just don’t like what I’m seeing now.

[00:11:02] And, we’ve got to get it back because I know it’s still there. I still meet Eugene every day. And I’m still one of the, you know, I have seniority, I’ve been here since 1967, and I don’t have many that can tell me what to do with my city.

[00:11:18] John Q: Native son William Scott Kramer talks about life on the streets of his hometown. An advisor for Sarah Koski and the Oregon Digital Safety Net, he is advocating for more public phone charging stations.

On Friday, July 21, we shared Will’s story with Eugene police officials. His allegations of being beaten while handcuffed will first be reviewed by the police auditor.

Updated July 29, 2023, as per SPJ Code of Ethics, #2, Minimize harm: “Consider the long-term implications of the extended reach and permanence of publication. Provide updated and more complete information as appropriate.”