Regenerate Cascadia: The land tells us how to organize ourselves

12 min read

Regenerate Cascadia visited Eugene in early October, with local permaculture tours and talks at Lost Valley and Dharmalaya. Christine Lorenz, Jon Van Meter, and Mike Brunt supported the tour, which examined the many threats facing the planet, and suggested how to start regenerating our home watersheds.

[00:00:19] Joe Brewer (Culture designer, Regenerate Cascadia): Planetary Boundaries is a framework developed by the Stockholm Resilience Center. It’s the collaboration of among about 3,500 scientists who study the dynamic Earth—people like geologists who study plate tectonics, people who study atmospheric chemistry, people who study rain formation, marine biologists, people who study ocean mixing and so on. Like, anyone who’s studying parts of the dynamic Earth.

[00:00:45] And in 2009, they asked this really interesting question: With everything we know about how the Earth works, are there any thresholds or boundaries, that if we crossed that boundary, that we would move out of the stable warm period called the Holocene, which is the only period in which we’ve had agriculture, permanent settlements of any kind, cities, empires, nation states, civilizations, a globalized economy.

[00:01:13] Are there any boundaries that if we cross them, the globalized civilization we have is called into question? And even the idea of population centers is called into question. And they found out that there are nine. There are nine planetary boundaries, that if we cross even one, then our globalized civilization probably goes away.

[00:01:32] So I just want to name them real quick, because:

(1) Climate change is only one of them.

2. Biosphere integrity, which is a measure of the rate of extinction, because if you hollow out ecosystems too much, they become fragile and collapse. So that’s a measure of the mass extinction event that we’re in.

3. Land system change, which is when you take complex, mature, healthy ecosystems and destroy them. For example, by turning them into agricultural land, urban landscapes, cutting down forests and turning them into desert. That all goes under the name of land system change.

4. Freshwater use. Because only 1% of all the water in the world is freshwater, 99% of the water is saltwater in the ocean. And if that fresh water becomes contaminated, or is not available, then our globalized system falls apart.

5. Biogeochemical flows, which refers to reactive nitrogen and phosphorus, which are used in synthetic fertilizers. And when it runs off of our fields, into our rivers, and into the ocean, it causes massive algal blooms, which then cause all the oxygen to collapse, and it causes massive dead zones in the ocean. So this reactive nitrogen and phosphorus, which is causing a collapse of marine ecosystems around the world.

6. Ocean acidification. If you have too much acidity in the ocean, then calcium carbonate for the bodies of coral or clamshells or all those different kinds of organisms, it actually dissolves their bones if the ocean is too acidic.

7. Atmospheric aerosol loading, which is just a fancy word for air pollution. If you have too much air pollution then you have…

8. Stratospheric ozone depletion, because in the stratosphere of the atmosphere, there’s this thick layer of ozone that actually keeps the dangerous ultraviolet radiation from hitting the Earth’s surface, which is the only reason that there’s any life on continents. There’d be no life on land without ozone.

9. And then this ninth one is called Novel entities, which is just a catch all for any weird chemical created by humans that the planet doesn’t know how to deal with. Microplastics are synthetic polymers created for industrial uses that are ubiquitous in the hydrological systems of the earth, including our bodies, and in every aquifer and every water supply on earth, in every drop of breast milk in every woman on Earth. And these are things that are hormone disruptors, and that damage the development of amphibians, and make your list of things it does.

[00:04:11] So, these scientists at the Stockholm Resilience Center identified nine planetary boundaries. And remember, if you cross just one, then the whole idea of our global civilization probably goes away.

[00:04:24] So, then there’s an obvious question. Have we crossed any of them? And so in 2015, they identified that we had already crossed four. The planetary boundaries for climate change, for the rate of extinction, for land system change, or the destruction of ecosystems, and for this reactive nitrogen and phosphorous.

[00:04:44] In 2021, they added two more: Fresh water use and ocean acidification. In 2022, they added microplastics. So we’re already very far from the safe operating range. They just had this published in Science about two months ago and did a press release.

[00:05:02] John Q: We may see weather systems start moving in 2030, and lose our typical rainy season in the Pacific Northwest.

[00:05:10] Joe Brewer (Regenerate Cascadia): If there’s global warming, the warming is amplified in the Arctic. It’s actually five to ten times as strong, the amount of warming at high latitudes than at the equator, which causes Arctic sea ice to melt. If Arctic sea ice melts, you go from 90 percent of sunlight reflected into space, because ice is white, to 90 percent of sunlight absorbed by the ocean, because the ocean is dark blue.

[00:05:35] And that causes more absorption of heat in the ocean, which causes more atmospheric warming, and you get this positive feedback, this accelerating process. And if there is a massive change in the heat distribution of the Arctic Ocean, it causes turbulence and chaos in the jet streams, which causes all of the weather systems on Earth to move.

[00:05:58] Which means you no longer have a stable rainy season in the Pacific Northwest. So this is just an example of how there are tipping points when you cross them, they have cascading consequences across the Earth.

[00:06:10] And so these breakdowns can unfold across space and time. But I want to emphasize this word across, which is that they unfold across multiple places at the same time with indirect relationships, where changes of ice in the Arctic can cause changes in the rain that happens in the Northwest, or they could change the rain that creates the monsoon pattern in the Southwest or the monsoon pattern in India, because they’re indirect relationships.

[00:06:40] This is what our earth scientists tell us. And so, when you look at a situation like this, do you think we can solve this by changing our light bulbs? Or do you think we can solve this by replacing the internal combustion engine in our single occupancy vehicles with electric batteries in our single occupancy vehicles, where those batteries require us to scrape the ocean floor or to engage in mountaintop removal mining to get the lithium for those batteries?

[00:07:08] And you start to see that our clean energy discourse is just a total joke, too. And so: What this requires of us is nothing less than a wholesale reimagining of the human presence on Earth. Now basically, there’s a real risk of extinction of the human species, along with millions of other species, that could be as soon as the next few decades, or as long as 200 years from now, but this is basically the state of the world.

[00:07:41] So, when we look at the world in this way, and we’re like, ‘What do we do about that?’ Is we have to engage in regeneration, on scales that seem impossible now, but they’re actually the minimum that we need to do.

[00:07:56] Now the silver lining in this story is that the systemic risk can be addressed by creating systemic resilience if we recognize that we now know a huge amount about how the Earth works. And this knowledge about how the Earth works, this knowledge of Earth as a set of integrated systems, shows us how to build up the resilience that connects across the different parts of the Earth.

[00:08:26] There’s a really profound way to understand what we need to do when we look at those planetary boundaries. And it comes from one of those statements that’s sort of like, seems really simple, but is actually really significant. And that is that ‘Everything that happens anywhere on Earth happens somewhere.’

[00:08:46] Which is to say, we’re in a place. And the place shows us how to create place-based transformation. You know, every place has its own unique geologic history. Every place has its own unique ecological history. And every place has its own unique cultural history, if humans have lived in that place. These three things together create a very powerful story for that place. So we’re in a place right here, where there’s a very specific geologic, ecological, and cultural history. And as you start to put together that history, what emerges is a set of whole system understandings about your place.

[00:09:28] What kind of place is this? What kind of life exists here? If humans have lived here, were they sustainable? And how were they sustainable? How did humans manage to have long-lasting cultural existence in this place? And as you come to these whole system understandings, you start to be able to imagine regenerative futures.

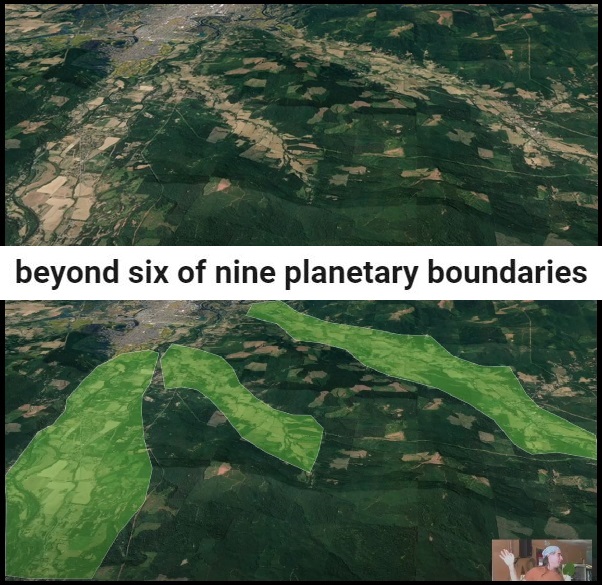

[00:09:52] And so to give an example, this is a screenshot I did from Google Earth. That’s Eugene, Oregon. But if you look at this, and ask where are the patterns of degradation in this landscape? My six-year-old daughter could draw it for you, right? You can see it, right? The degradation is in the valleys. That’s where they cut down the forest, that’s where they put in the agriculture. The urban setting is at the confluence of the McKenzie and the Willamette River. And you start to see that if you wanted to regenerate this landscape, you could actually organize yourselves according to the patterns of the landscape.

[00:10:30] This drainage is maybe 10 miles from one end to the other, maybe three to four miles across, and you start to see a human scale of organizing. You can imagine, if we wanted to restore the health of that valley, maybe it’s 100 pieces of private land, and we just go and talk to the landowners, and create a landscape plan for the regeneration of that valley.

[00:10:55] We might start doing watershed restoration, as you always do with water, by going to the top and working your way down, right? And you can see that this is a human scale of organizing. So if you wanted to regenerate the area around Eugene, you could start regenerating these local watersheds, these local drainages.

[00:11:14] What’s interesting about this is that when you go to a larger scale, the Willamette Valley, from Eugene to Portland, is about 100 miles. So it’s maybe 100 miles end to end, 50 miles east to west. It’s a pretty big land system. Lots of rivers coming into it. But, if you ask, ‘How would you organize to regenerate that?’ The answer is the same thing. You would just go to these local drainages and start organizing parallel projects, right?

[00:11:41] You can imagine maybe there are 30 or 40 watershed level projects for all of the drainages into the Willamette Valley. Each one of them locally organized as a land system in its own right. So, to regenerate the Willamette, we’d have to organize multiple of them in parallel. But it’s exactly the same process, so we’d already know how to do it.

[00:12:07] Now when I go to the scale of something larger, like the Columbia Basin, Columbia Basin is 258,000 square miles, same size as the Colorado River Basin, it’s huge. There are 174 rivers that drain into the Columbia. This is a massive watershed system, but the way to organize it is fractal. You organize local projects at a human scale and replicate them up and down the hydrological system. And you could regenerate the entire Columbia Basin. And so it’s this way of thinking that reveals a powerful way to organize local landscapes.

[00:12:46] And I just want to notice that we should expect human economies to be diverse around the world. Because the way that you would build an economy for a human presence in temperate rainforests like you have here, would be very, very different from in a dry land ecology like you’d find in Southeast Asia, or like in the Middle East.

[00:13:09] And so, we should expect that regenerative cultures and regenerative economies are diverse around the world.

[00:13:16] And so, with that in mind, there was this really famous study that came out in 1972, the first computer simulation of the human economy at the planetary scale. It was called Limits to Growth. And in that study, they showed that if we followed the course of what’s called ‘Business as usual,’ which is a phrase that they invented for that study, that we would have exactly the kinds of breakdown and collapse that are happening now, because even though ‘Business as usual’ was not a forecast, reality has tracked it almost perfectly.

[00:13:47] And so after that study came out, there was a period of 10 years where some of the best thinkers around the world, between 1972 and 1983, held meetings to discuss how do we live within planetary limits. And they were called the Balaton Group because their first meetings were in, were at Lake Balaton, which is in Hungary. Dana Meadows, who is the lead author of that Limits to Growth study, she wrote an essay called A Brief History of the Balaton Group, which resurfaced in the last couple of years, and people are starting to read it.

[00:14:18] So in 1983, Vernon Ruttan, an agro-economist (an economist of food systems), said each agro-economic region is so unique that ‘the concept of transfer of technology is irrelevant.’ What’s relevant is the transfer of the capacity to develop technology and institutions that are consistent with the cultural endowment and resource endowment of each region, which means every place on earth needs to learn how to build the institutions that it needs to be able to manage itself as a unique place.

[00:14:51] So in 1983, the best thinkers in the world working on sustainability said the only way to create planetary sustainability is to create local living economies organized as bioregions and for each bioregion to have its own bioregional learning center.

[00:15:09] And a major role of bioregional learning centers is to assist in the coordination of indigenous knowledge and indigenous sovereignty in creating and managing that knowledge as it relates to the local economy.

[00:15:23] Ecosystems are all about relationships. Bioregional learning centers are all about relationships. And when we go from this to looking at territorial governance, it’s like, how does territorial governance work in these bioregional regeneration processes? One thing is that they’re about mapping and weaving local projects.

[00:15:42] Now why is this about governance? Well, how do you map local projects? Well, you need to actually gather representatives of those projects to tell you what’s happening in them. And then as they come together and they start sharing knowledge, they’re able to start making decisions together. So this allows you to start to identify needs and priorities across existing projects or to create new projects that don’t currently exist.

[00:16:07] And this is about decision making and allocation of resources, so it’s about governance. It allows you to form landscape partnerships where you can have collaboration among different actors who care about the same things. So like, if you have a river and you say, we want salmon in this river, so there’s like a shared purpose. Who are all the different actors that need to come together?

[00:16:30] You need to form landscape partnerships to be able to do something like bring the salmon back to a river. As you do this, you’ll start to see that most of the way that funding is allocated now is not very collaborative and also not very intelligent, which means that you’ll need to start creating community funding structures.

[00:16:48] Another way of saying this is: As partnerships form, as they set priorities and they identify their needs, as they map their projects and their capacities, they start to discover what is valuable and how it can be exchanged, which isn’t just limited to money. It could be knowledge, infrastructure, places, any number of things.

[00:17:09] You start to create community funding structures… alternative economic models. Doing things like creating solidarity exchanges that don’t involve money. Creating a community shop where we now have about 80 local producers collaborating and sharing things. Creating time banking tools and doing things like creating community currencies. And all kinds of things that allow them to function.

[00:17:31] All of this is cultivating local sovereignty. Because increasingly resources are mobilized locally and decisions are made locally by members of the community. This is actually how sovereignty is created, is through this process. And this strengthens internal collaboration, strengthens shared identity, strengthens the political capacity, the institutional capacity locally.

[00:17:56] So this is like the opposite of globalization, right? This is the undoing of globalization in that sense. This is the re-localization of governance and economics.

[00:18:07] I hope it’s clear by looking at the tipping points of the Earth system and the planetary boundaries, the only way to organize that’s going to have any chance is to organize landscapes and relationships between them. And that this is like a 200- to 500-year project. This is the big work of humanity is to actually do this work.

[00:18:28] John Q: Culture designer Joe Brewer visits Eugene on the Regenerate Cascadia tour, to share the path to preserving human life on the planet: ‘Nothing short of a spiritual revival of indigenous lifeways will do.’

[00:18:39] His book is titled The Design Pathway for Regenerating Earth. Learn more at RegenerateCascadia.org.