Opportunity costs, opportunities lost: The hidden high costs of theft, vandalism, and homelessness

6 min read

by Ted M. Coopman

“I think the real solutions for the long term here involve increasing the size of the pie rather than arguing over the slices.”

—Eugene City Councilor Mike Clark

Most discussions on homelessness and any real or perceived association with theft and vandalism focus on the homeless themselves, interaction with the police, services dedicated to them, or funding those services. What often gets ignored are the impacts on the larger community and that those impacts disproportionately fall on the working poor and small locally-owned businesses—essentially those who can least afford it.

These impacts are magnified when self-appointed compassion cops add insult to injury by trivializing victims’ pain or outright attacking them for their lack of empathy. Anyone on Nextdoor has witnessed tactless comments about how it is “only stuff” when a neighbor reports a porch pirate or that “whoever stole it must have needed it,” followed by how that person’s loss “is nothing compared to the trauma of homelessness.” Maybe, but the fact that “what the unhoused endure is nothing compared to the slaughter of civilians in Ukraine, Gaza, or Israel,” while true, is hardly relevant. It is easy to be self-righteous when you are not the one experiencing it.

Shifting or “externalizing” the costs of the impacts of homelessness is the biggest untold story of the housing/homelessness crisis. In this case, the social costs of our failed strategies are externalized to people or businesses who happen to reside in certain neighborhoods, mostly in West Eugene.

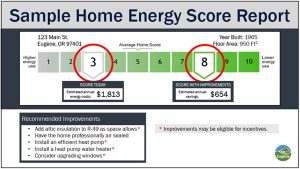

The upfront costs of theft or vandalism are evident. Parks and Open Space spends about $300,000 a year to repair vandalized bathrooms and Public Works will spend another $476,000 a year to clean up unsanctioned camps and right-of-way areas. Homeowners add Ring door cameras and security systems. Businesses install expensive fencing and other barriers or pay for security and cleaning up trash and human waste.

While mitigation costs are easily observed, opportunity costs are hidden. In economics, opportunity costs refer to what you have to forego to spend on other priorities. For a business this might be foregoing more inventory to pay for fencing. For homeowners this might be waiting another few years to paint the house and instead install a security system.

For property owners, but especially businesses, the costs of forgone opportunities have direct material impacts on the Eugene economy. It is not about minor choices, but major expenditures. Opportunity costs encompass direct physical trade-offs, strategic choices, and emotional arbitrage.

The direct physical trade-offs are the easiest to grasp. If I spend $20K on new fencing, I can’t afford to buy new equipment. A retail item may be profitable, but less so due to theft (shrinkage in retail-speak). And once you install anti-theft measures, offering the item may be more expensive than it’s worth. Repairing vandalized property, calling in a hazmat service, or having to buy and maintain planters, rocks, or other material to dissuade illegal camping are all non-productive expenses. Money spent here is not money spent productively on growing a business, adding staff, or paying higher wages.

For residential property, homeowners must replace stolen or destroyed property, change landscaping, get security systems, upgrade locks, or add a fence. For landlords, proximate street homelessness complicates getting and keeping tenants and takes money from improving the property. For renters, added expenses for landlords means higher rents to offset these costs.

Strategic choices are where the problem really starts to bite. If there are ongoing problems that may or may not get worse, they impact any decision on expansion or investment. Relocating a business is expensive and a hassle, but when conditions deteriorate, the cost-benefit analysis changes. Even the extra costs of longer travel times might be mitigated by relocating. Will it be easier to keep staff if they do not have run a gauntlet of trash and campers to and from work? For residential property owners, especially those who live in their homes, the stress and expense may become too much. I have lost count of how many neighbors have told me the same story: “We love our home, we love our neighborhood, and we love our neighbors, but we can’t live like this anymore.”

Please, take a moment to consider what it would take for you sell your home and move with all the hassle and expense. This is especially acute for families with children. What do you do when your grade-schooler tells you they are afraid to go out front and play?

That leads us to the psychological and emotional impacts on decision making: Is the situation going to improve? Is the stress too much? Is it worthwhile to stay? Sadly, the emotional costs of constant exposure to illegal camping, public drug use, mental health crises, human waste, discarded syringes, piles of trash, and the uncertainty of what you will find and must deal with in the morning, every morning, is too much. This sort of fear and, yes, trauma, often gets ignored.

Compounding all the material, strategic, and emotional impacts is the inability and unwillingness of local government to come to your aid. It is a lonely feeling when there is no one to call who will come help because there is not enough staff. Then there is the frustration over an apparent outsize concern for folks on the street that negates any empathy for the impacts to residents or businesses. Most maddening of all are the ill-conceived laws, processes, and procedures that make addressing these issues nearly impossible. Getting countermeasures implemented such as parking restrictions are a long and complicated process and are only as good as the ability and willingness of the city to enforce them. Again, as a neighborhood leader, I get emails and calls from neighbors (even one as I wrote this) who simply do not know what to do or whom to call, and can’t understand why their government can’t do anything to help them.

These opportunity costs compound on each other as we change behaviors based on similarly-impacted neighbors and businesses. Opportunity costs collectively degrade the local economy and the viability of neighborhoods. These opportunity costs are an equity train wreck as those who can afford to mitigate problems or leave do so, and those who cannot simply suffer the consequences.

So, when we talk of homelessness and its costs, we need to consider ALL the cost and ALL the different people who are “experiencing homelessness” while not being homeless themselves. That number is considerably higher than those on the streets. And this is why solving the homeless crisis is not about compassion for a few, but survival for our entire community. Eugene simply cannot survive as a viable community unless we recognize the problem for what it is, how far-reaching its impacts are, and take the needed steps to address it. We simply do not have a choice.

Western Exposure is a semi-regular column that looks at issues and challenges from a West Eugene perspective – a perspective that is often ignored or trivialized by city leadership and influential groups and individuals largely based in south and east Eugene.

Western Exposure rejects the fauxgressive party line, performative politics, and “unicorn ranching” policy in favor of pragmatism focused on the daily experiences of residents and small businesses in Eugene—and West Eugene in particular.

Ted M. Coopman has been involved in neighborhood issues since 2016 as an elected board member, and now chair, of Jefferson Westside Neighbors and has 30+ years experience as an activist and community organizer. He earned a Ph.D. in Communication (University of Washington) and served on the faculty at San Jose State University from 2007 to 2020.

Ted’s research on social movements, activist use of technology, media law and policy, and online pedagogy has been published and presented internationally and he taught classes ranging from research methodology to global media systems. He and his spouse live in Jefferson Westside with an energetic coltriever and some very demanding and prolific fruit trees.