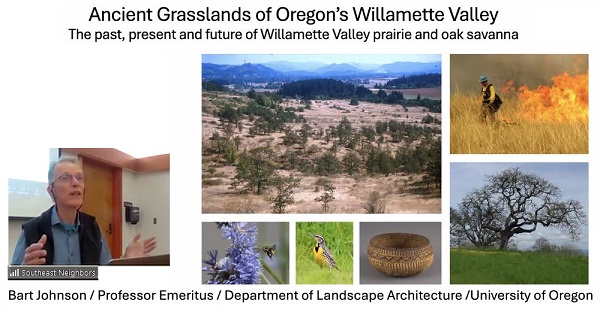

Bart Johnson: Consider prescribed fire in South Eugene neighborhoods

11 min read

Southeast Neighbors welcomed Bart Johnson, professor emeritus of landscape architecture at the University of Oregon, to speak on wildfire, fire stewardship, and enhancing our capacity to adapt and innovate in the face of climate change. On March 12:

Bart Johnson (Professor emeritus, University of Oregon): I’m a wildfire researcher. I’ve worked with prescribed fire, I’ve worked with landowners… Particularly under climate change, the lessons from the past are insufficient. So we’re trying to be able to look ahead, to understand how the landscape is changing, settlement is changing, to understand how we get ahead of the curve here before a disaster happens.

[00:00:35] I want to talk about how we might act in the South Hills at three scales. So I want to give some just basics on understanding wildfire and risk to empower you when you’re looking at (1) your land and your house and (2) the neighborhood, you can actually start to think in the way that fire looks at and perceives (3) the landscape.

[00:00:51] So, if those of you remember that night during the Holiday Farm Fire when the fire really blew up, it was these weird winds coming out of the east. It was hot, it was dry. What the heck’s going on?

[00:01:02] And by the next day, when you looked online, there’d been a 20,000-acre fire and suddenly it was 100,000 acres overnight. I just thought, ‘Somebody made a mistake. When are they going to correct this on the news,’ right? ‘It’s got to be an error.’

[00:01:13] It wasn’t new that we have large fires in our area. It’s not new to have large fires due to east winds, but what is new is that we’re facing increased aridity with hotter, drier summers. We have longer fire seasons, and we’re likely to develop more overlap between our fire season and the foehn winds.

[00:01:30] In California, they call them the ‘Santa Anas,’ or the ‘diablo’ winds in Colorado. And what essentially has happened, for instance, in California, is the Santa Ana winds are actually weakening under climate change. But the fire season is extending longer into the season of the winds, and that could happen with us.

[00:01:47] That’s not the only way we can get large fires here, but it certainly is what happened in 2020. And, you know, it was just like a blowtorch, so that even areas along the river that normally would have such high humidity, they’ve been less likely to burn—it just torched, like that.

[00:01:59] This is an account from a landowner to give you a sense of what he faced: “An alarm went off on both our phones. I woke startled, not sure exactly what was happening. The text message said, ‘Evacuate now. You have five minutes. Do not collect anything. Leave now.’ My wife grabbed the cat and put her in the cat carrier. Our phones were our only light. I’m hopping on my left foot and grab my computer, iPad, and briefcase. Outside there was thick smoke and bugs everywhere, so thick you’d breathe them into your nose and mouth. I was useless on crutches. We got our dog and the cat into the Honda CR-V. My wife grabbed two pictures; one a photograph of her mother when she was three, and a valuable piece of art hanging onto it.”

[00:02:37] That was all they got out of their house, right? And just a tremendous loss there. Luckily, they had insurance. It worked out over time. They were among the lucky in that sense. He recommends if you’re in a fire danger zone: Have a go bag. Be ready. Just be prepared for what’s going on.

[00:02:53] So, some of our research has been simulation modeling. The future won’t be like the past. You’ve got to rethink what it means to have a good landscape around our homes and where we live. We have to think differently about it.

And when we simulate them, say, actually in the future, we’re not going to have that much different wildfire up until about 2050. And then it gets a bit more, but it’s not that different from the past.

[00:03:14] And over time what we’re seeing is both hazard is going up in our landscape with increased fuels, but also risk is going up due to climate change, due to the values that we put in the way of that.

[00:03:26] So risk is increased in our landscape because of the loss of Indigenous fire, fire suppression, Smokey the Bear since the 1920s or so, leading to increased fuels. And now we put more homes and people out in the middle of wildland fuels with their risk. People want to enjoy being out in nature. We want naturalness around us. And now we’ve got climate change on top of it.

[00:03:48] So all of those factors have contributed to increasing risk.

[00:03:53] When we look backward in time at our landscape, I think Mount Pisgah is a pretty good window into the past, that most of our landscape here was dominated by upland oak savanna and grassland. Imagine a fire burning through this: It’s going to burn through the grasses. Maybe a few trees torch, but it’s a very different fire than in a dense conifer forest.

[00:04:12] And so what’s happened over time is we’ve gone from these open savannas with scattered trees that have infilled with Doug(las) firs coming in, turned into these dense conifer forests. That’s a whole different beast when it comes to wildfire. Now you can have canopy fires. Now instead of flames that are one to two to 10-foot high, you can have flames that are 150-foot high. And that changes risk pretty dramatically.

[00:04:35] One of the first lessons when we get into dense urban areas is that one of the key ways that fire can spread is from one structure to another structure. So that becomes one of the main dangers within denser urban zones: Not just the vegetation around you, but your house igniting, your neighbor’s house igniting. And if you haven’t seen the film out of, it was either Talent or Phoenix during that fire, and, you want to be horrified, look at it, because the flames are blowing sideways, and it’s just literally one house torching another, torching another.

[00:05:04] And that’s why Almeda Drive, the smallest of all the fires, 3,200 acres, 3,000 structures burned. That’s the one that really got into an urban density area.

[00:05:13] And so let’s think about (1) your home and your lot. Let’s think about (2) the neighborhood, my house, your house, the houses around the center block. And let’s think about (3) the landscape. Let’s think about all the South Hills. And by that, I don’t just mean the area where we have our houses. I mean about the South Hills and the Ridgeline Trail system up there, which is both a potential source of risk, but also a potential source of buffering us from fires that might come from the south, if it’s managed well.

[00:05:38] So to think like wildfire: There’s a number of ways that wildfires can go wrong there. There’s the east winds, the dry east winds that come like a blowtorch. We have to think about surface fires and ground fires. Keep in mind again that what transmits fires, one, it can be direct spread from fuel to fuel to fuel, particularly on a slope, where fire is burning and preheating the fuels above it and drying them out. That’s why fire can move up quickly on the slope.

[00:06:04] But you can also have embers spotting, particularly when trees are torching or there’s a crown fire. They’re sending out sparks. The wood can create embers that can carry two miles. And now you’ve got fires that are spotting ahead. People have to try to suppress them and get ahead of it. So that makes it really difficult.

[00:06:20] And then finally, again, structure fires, from one house to the other.

[00:06:24] And you want to think about: What am I going to do to reduce risk? You have to keep all these factors in mind and look around you to be able to evaluate it.

[00:06:31] So one of the key strategies is thinning the trees to keep space between the tree crowns, so it’s harder for the fire to go from one tree to another, particularly to set off a crown fire. And you remove the ladder fuels, things that carry it from the ground fuels up. You create discontinuity between it.

[00:06:48] So if we do all these mitigation activities, and we do it purely for fire, and then we never have a fire, we just lost / wasted a lot of resources and effort.

[00:06:56] So think about creating a beautiful place around your home. Think about gardens. Think about wildlife habitat. Think about recreational corridors out in the South Hills. Think about more than just wildfire when you’re putting in mitigated action.

[00:07:10] So: Urban town center, you’re mostly in an ember zone. You don’t have that many fuels to burn, but you can get hit by embers. We’re more in this sort of general residential suburban area.

[00:07:19] It’s not hard to build homes and houses and landscapes that won’t burn, where you’re completely fireproof. You can use Firewise construction materials, fire-resilient building materials, certainly metal roofs. But the point I want to make is, that’s all good, but many times when homes set fire, it’s because people may have leaves in their gutters, they start to burn, and then the embers get pulled into the vents that are underneath your rafters there.

[00:07:44] So there are now people coming out with spark arrestors that will stop that. That may be one of the biggest things that we can do in the future to prevent burning homes, is to put in things like the spark arrestors. Once the fire gets inside your home, it’ll just, could just blow up because you’ve got wood construction inside.

[00:07:59] Focus in the home ignition zone is really important: under your porch, against the house, the gutters, just places where sparks can lie and ignite your home and particularly come in through spaces, cracks in your house and get inside.

[00:08:11] One of the classical strategies is defensible space. You need to manage the vegetation around your home. One of the lessons I’ve learned along is: Don’t freak out. You don’t need to create a death zone of nothing around your house to do this.

[00:08:23] At the neighborhood scale, the key issue is that these ignition zones overlap. What your neighbor does matters to you and how you work together with your neighbor matters. You really have to work together as a neighborhood.

[00:08:36] Think about more than wildfire. Think about making a beautiful place to live for yourself. You can create vegetation that’s fire-resilient and unlikely to burn in ways that endanger your house. You can create pollinator gardens. You can use more fire-resistant plants. You can create water features. You can have irrigated gardens around your home.

[00:08:53] For instance, when we worked with our landowners up in Goodpasture Lane, part of it was like, if you’re creating these sort of shrubby areas and patches of space between them, think about the sight lines to your neighbors. Maybe you’d rather have some privacy. So build that into the fire resilience that you have there.

[00:09:09] Again, we live in an area that was largely the savannah grasslands. Because they filled in and become dense conifer forests, they create a much different hazard, and through that, much greater risk for us.

[00:09:20] So, a lot of my work is about how we combine restoration at landscape scales and home scales with these oak savannah landscapes, with scattered oaks, grasslands, other vegetation as a way to mitigate fire.

[00:09:32] Grasslands can have long flame lengths, but that’s nothing compared to what happens in a forest fire.

[00:09:38] So, again, a lot of my work is thinking about lots of reasons in which we can use oak savannah restoration, grassland restoration, other features to pre-adapt to wildfire and create mosaics of grassland that are not only good habitat for wildlife, but create suppression points. They interrupt the flow of fire, even if there are untreated forests nearby.

[00:09:59] And in the South Hills, the idea of creating shaded fuel breaks, restoring oak woodland savannah, providing access points and trail systems for fire management, prescribed fire and suppression, and linking risk reduction to open space recreation, habitat restoration, and reintroducing good fire, prescribed fire.

[00:10:16] So I hope that as a neighborhood, we can advocate for this kind of management out in the South Hills, because there are a lot of people who don’t want to see it change. They don’t want to see trees cut. They don’t want to see anything happen. But I would argue differently.

[00:10:28] You can create fuel breaks. There are ways to treat that to make it more fire-resilient, creating habitat for wildlife. You can do this in your backyard, you can do it at the scale of the South Hills.

[00:10:38] We think about the pathways through which fire can come to Eugene. Clearly, we have these east wind events that can drive down the valleys. But I’d also argue that when we’re under south winds, the Ridgeline Trail system can be either a hazard for us or it can be a buffer, depending on how it’s managed. The city is trying to do a good job. They face a lot of resistance.

[00:10:57] And lastly, just think about prescribed fire stewardship. Prescribed fire generates smoke. People don’t like smoke. There are health issues. There are allergies we have to pay attention to. But the difference between a prescribed fire smoke and what happens when a Holiday Farm Fire occurs is pretty dramatic.

[00:11:14] In particular, when you’re in areas where houses are burning, that’s when the toxics are coming out. When plastics, all these things that are in our homes are burning, we create an extraordinary health hazard. So, we can talk about it more. I’m a big advocate for bringing prescribed fire into our neighborhoods.

[00:11:28] And the last thing is: Think about how you work with your neighbors. I live right here on Tugman Park. I’ve got a woodland next to me. I got a lot of fuels around me. I’ve seen people who live in dense downtown urban Eugene freaked out during the Holiday Farm Fire that they were going to burn up. And I was like, ‘You know, I don’t think you have too much to worry about. There’s no fuels around, you know, it’s just very unlikely to happen.’

[00:11:48] I’m near a lot of fuels. I’m actually not super concerned because I’ve kept it clear around my home. The vegetation right around my home is not likely to burn, and I feel I’m in pretty good condition. Sure, I’m worried about fire igniting things around my house, but I’m not going to freak out and change my landscape about it. But I am taking care. So: Don’t do too little, but don’t go crazy.

[00:12:11] John Q: Professor emeritus Bart Johnson, whose research into resiliency led him to advocate for prescribed fire and landscape restoration, including right here in the neighborhoods of South Eugene.

[00:12:21] He suggests that before the fire season begins: Trim any flammable materials touching your house, reduce ladder fuels that might let a surface fire become a crown fire, and clean out your gutters. For more information, contact your neighborhood association.