PSU climate scientist inspires Scobert Gardens Park petitioners

5 min read

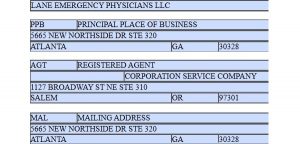

Whiteaker residents asking the city to restore lost trees in a neighborhood park have the support of an influential climate scientist. PSU’s Dr. Vivek Shandas, one of the authors of the 2023 Fifth National Climate Assessment‘s chapter on the Northwest says: As the climate warms, we should think more about trees.

[00:00:18] Dr. Vivek Shandas (PSU, Fifth National Climate Assessment): My name is Vivek Shandas. I’m a professor of climate adaptation at Portland State University, and I study the intersection of built environment, environmental health, and climate change in relation to historic planning policies in cities.

[00:00:38] Trees are one of the original air conditioning systems for the earth. We know that; they, along with water and wind, and they can reduce temperatures in cities by upwards of 20 degrees F. In some cases, green spaces along a building wall, such as a green wall, can reduce temperatures by upwards of 50 degrees F. So it’s fair to say that green spaces through their shading of sidewalks or shading of walls can reduce temperatures.

[00:01:08] They’re also evapotranspiring lots of water by pulling it up through their roots and transpiring it through their leaves. And that also adds directly to the cooling of the surrounding environment.

[00:01:22] Trees work in two primary ways. They offer a means by which particles in the air can deposit on the leaves or needles. And they’re also able to uptake gases through small little holes called stomata on the underside of leaves that actually bring in some of these gases that are produced either from cars or other forms of combustion. And they’re really able to reduce air pollution through those two processes.

[00:01:52] I will note that some trees also can shade parking lots during hot days and that reduces the evaporation of gas in gas tanks, which often creates what’s called volatile organic compounds. So it really underscores the need for thinking about where the trees are in relation to what services that they’re providing us.

[00:02:14] Trees are really helpful to human health in four different ways. The first is physical health. They’re really able to improve our cardiovascular as well as respiratory health through improving air quality as well as shading the communities, from extreme heat. The second way is trees help social health through building social cohesion among communities.

[00:02:35] We see several studies that indicate that communities that live near forests or parks or even large number of street trees are much more connected socially, they spend more time together. They trust each other more, and that’s different than those communities that don’t live around a lot of trees.

[00:02:53] The third is around mental health. We’ve seen several studies come out that show that issues of anxiety, mood, depression are all alleviated through being around trees. In fact, there’s some cultures where studies have occurred where we can find that people doing forest bathing, a practice that’s been common in many parts of Asia actually really helps in addressing and improving the sympathetic nervous system, which really has to do with the body repair and enabling our immune system to respond more effectively.

[00:03:28] And then finally, one area that has got a lot of evidence is around birth outcomes. We’re finding that trees, forests, and green spaces generally are really helpful for pregnant mothers because we see better birth outcomes when mothers are around trees and spending more time in green spaces, whether at their home or even outside of their home in parks and other green spaces in the community.

[00:03:54] Trees are really helpful in terms of sequestering carbon in their physical kind of trunk and their leaves and their roots, and they’re also amazing in terms of keeping carbon in the soil. So they’re helpful in terms of greenhouse gases. If you compare it to a vast forest, it pales in comparison, though trees in the city play an arguably smaller though important role in terms of keeping keeping carbon in the soil as well as sequestering it in the trunks and leaves and different parts of the tree as well.

[00:04:30] We’ve seen over the decades that the distribution of trees is very inequitable across our cities, and that’s in large part due to historic segregation policies that have really baked in these vast spaces of land that are sealed up by asphalt and concrete where it’s hard to get a tree into the ground. And those policies that are still casting a long shadow in terms of being able to right some of those historic wrongs is right at the center of a lot of the investments that are currently being made in cities to improve and expand the tree canopy in historically segregated and marginalized areas of cities.

[00:05:15] We know, for example, that in a place like LA, 19% of the trees are in areas where only 1% of the population lives. And we really need to be thinking about how do we bring green spaces with communities, for communities, into places that haven’t historically had a lot of green space. It’s not an easy puzzle, but it’s something I think we’re all really eager to try to figure out.

[00:05:42] We do know that places that have a dedicated urban forestry division, ideally an urban forester, and resources to be able to do programming, places that have urban forestry management plans, places that have good data on where the trees are and what condition those trees are in usually fare much better than those places that don’t have good data or don’t have dedicated governance structures to be able to manage all of the different green spaces in a city.

[00:06:12] So there are many factors that go into ensuring that an urban forest is doing well and the effectiveness is largely in part based on having these factors really align.

[00:06:25] We’ve often pitted the tree against the building, and this is a narrative that comes from a long history of city design and development, and what I’d really like to convey is that this is really a question about how we’re going about designing our cities.

[00:06:42] A lot of the ability to accommodate green space in our cities is about how we’re thinking about our homes, our buildings, our roads, and whether we would allow space for trees and for greenery. As the climate warms, we’re going to see a lot more hotter days. We’re going to see a lot wetter winters throughout the country and being able to think about trees as a frontline defense for those hotter summers / wetter winters will be a really important point to underscore, I think, going forward.

[00:07:15] John Q: That’s Dr. Vivek Shandas on SciLine, a service from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. His work inspired Whiteaker residents petitioning for more trees in Scobert Gardens Park, and he in turn praised the petitioners: “Despite well-intentioned efforts, it’s people like you and work like this that moves action.” As of July 16: 344 people have signed the petition. Learn more July 23 at a meeting at the park, 1180 W. 4th, starting at 5:30 p.m.

Image: Cover art by Claire Seaman for the chapter on the Northwest in the 2023 Fifth National Climate Assessment.