Human Rights Commission helps UO students explore hostile architecture

12 min read

Presenter: The Human Rights Commission is helping University of Oregon students identify hostile architecture. At the Nov. 5 Homelessness and Poverty Work Group:

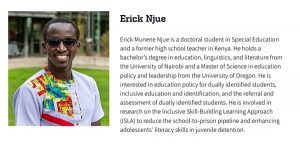

[00:00:10] Blake Burrell (Human Rights Commission, HAPWG): Solmaz (Kive) is a professor at the University of Oregon who has been working in collaboration with social service providers and I invited her thinking about ways that our various groups could provide insight to students on hostile design and we can brainstorm a little bit how we might engage.

[00:00:30] Solmaz Kive (UO): Thanks, Blake, and thanks everyone for your time. Hostile architecture—that’s the architecture of public ‘furniture’ that are used or designed in a way to discourage people from using the public space.

[00:00:46] The very famous example is, of course, the handrests on the benches. But as I’m sure all of you know, we have quite a lot of other examples in Eugene as well.

[00:00:56] So the goal is for students both to understand the city a little better and really engage with the community at a more personal level—so really increasing their understanding and level of understanding when they are designing something. So that’s the overall goal that I have in mind with that.

[00:01:16] So the activities that the students do, that was one of the things that I wanted to discuss with you.

[00:01:20] Another one is that when we are analyzing and discussing the examples of hostile architecture in Eugene, what are different frameworks? For example, we can talk about them in terms of the agent who does that: Is it a public or a private agent?

[00:01:35] We can talk about the ways that the piece of design is working: Is it something that’s preventing people? Is it a coercive measure? Is it an explicit or an implicit measure?

[00:01:47] We can talk about the strategies that they use something: For example, do they change the bench? Do they add something to it? Do they completely remove any type of facilities from the public space?

[00:01:59] Or we can talk about other aspects of it in terms of how that hostility is disguised in a way. So when we are comparing something like spikes, which are more common in some places like London, for example, they are much more explicit.

[00:02:15] But when we are talking about something like the boulders or bike racks, things of that sort, they are not very explicit. A lot of people don’t understand—some people get alarmed when they see those explicit measures. But when people don’t see those explicit measures, usually you see much less reaction from people who are more concerned about the inclusion in the city.

[00:02:37] So that’s the framework ones, but I think probably the activities is the best place to start with.

[00:02:43] The part that I really need help with is the type of activities that engage students with the activists and with the community.

[00:02:53] So one is I think definitely lectures and another one that Blake suggested and I thought was amazing was focus groups. Students do some initial studies and then they present it to the focus group and get some feedbacks from the focus group. But I need some help on developing that idea a little better.

[00:03:12] So let’s say the first one is more for students to understand and understand the scope of the issue and that could be more than just hostile design—understanding the scope of homelessness in Eugene and how that actually affects people’s life. And then the second one could be the presentation of their finding and getting feedback from people.

[00:03:32] And then another question I had was, which is very much related to the activities, hopefully we are also producing something that could be used for advocate groups.

[00:03:42] Presenter: For example, the students could create maps of Eugene, showing different types of hostile architecture.

[00:03:49] Jolene Bettles (HAPWG): I’m really resonating with this work. This matches and mirrors a lot of the education I received at the University of Oregon as a sociology major and graduate with a legal studies minor, ethnic studies, Native American studies minor. And when I’m looking at Eugene as a community with hostile architecture, the one thing I noticed has to do with transportation. Because years ago, there used to be covered bus stops in the Four Corners neighborhood, where a lot of our unhoused population is right now.

[00:04:22] And over time, those were taken away and removed. So now we no longer have a place to sit if someone is at the bus stop in Four Corners. And if you go to the University of Oregon, I see covered bus stops, you know, and so I do see this being perpetuated in our community and it becomes quite normalized.

[00:04:44] Solmaz Kive (UO): The bus stop is one of the great examples for it. Some of them completely remove it, some of them intentionally design it in a way that you have split seats so you can’t really use it for sleeping or anything that they don’t consider as a ‘proper use.’

[00:05:01] Richard Self (HAPWG): One of the things you can bring into this conversation, as we have tried to do with the criminalization of homelessness overall, is the cost of doing the hostile architecture. It costs a lot of money to dump a bunch of rocks where people were sleeping the night before. It costs a lot of money to make a bench that used to be able to be slept on with one more armrest or what have you, right in the middle of it, so it can’t be slept on anymore.

[00:05:33] It costs a lot of money to do that and as she just pointed out, it costs a lot of money to remove the bus bench and the covering and throw that in the trash. It just costs a lot more. So the cost of these things for the taxpayers ought to be brought into the conversation.

[00:05:53] Solmaz Kive (UO): That’s a very, very great example. Let’s say a group of two, three students to pick one of these examples and just really go and estimate the cost that it causes. And I know I had earlier some of my students, they found the statistics for the boulders. I don’t have the number off the top of my head, but that was a ridiculous amount of money used for that. But I think that’s a great idea.

[00:06:20] Jolene Bettles (HAPWG): I am interested in continued collaboration with students. I do see the students that are coming out of the University of Oregon as beacons of hope, especially when it comes to change-making and continued work within our community.

And another point that’s harder to nail down is when we think about how our socialscapes are formed, even just with transportation, like, who gets to have the ability to maneuver at will and who has to be relegated to bus stops with no coverings, with a limited Sunday bus schedule, for example, where it takes you four hours to go to one place.

[00:07:00] So there’s definitely social class struggles that are occurring here and that are shaping our everyday lives and experiences.

[00:07:07] And for me, the thing that comes to mind is accessibility: Who has access to a place to sleep at night? Who has access to transportation, who has access to opportunity, who has the messaging, and that social conditioning where it’s like, ‘Yes, this is a place for you and you belong.’ And I’m kind of gleaning a lot of that from your work, because we can talk about benches, but you know, this is the socialscape that shapes our outcomes as community members.

[00:07:36] I would say go across town to do a task, to do an appointment by a certain time on Sunday, like, if you had to pick up a prescription, you know, all the steps and all the organization that you’d have to do.

[00:07:48] And then just kind of pay attention to how long that takes, how long you’re waiting at the station, because people waiting at the bus station historically have been a problem or viewed as a problem. They used to have classical music that was playing on a loop just to deter people from the downtown area. (Exactly.)

[00:08:08] Blake Burrell (Human Rights Commission, HAPWG): One thing that might relate to some of the work of our working group is having students explore the physical constraints of space that people are allowed to reside outside.

[00:08:22] So the city of Eugene currently has not provided a jurisdictional map for where individuals are allowed to reside when they’re unsheltered. So we operate largely when we’re doing street outreach from this perspective of advising people on where they cannot go, but we don’t really have guidance on where individuals can go.

[00:08:45] So we operate a lot under that kind of style. So if you’re non-established, Parks and Open Space can give you a two-hour notice. If you have an established camp under their definition, they say that they’ll give you 24-hour notice. If you’re in a public way, they have to post and give a 72-hour notice, right?

[00:09:08] And so we could think about these different geographies that have political enforcement constraints on them and look at hostile architecture within those spaces. Like if you go through a park, right, and say you’re on the river trail. It’s really common to see boulders or rocks or things like that under bridges, which would be like really accommodating structures, helping people stay out of the rain. And is there a correlation between the use of those hostile architecture elements and those enforcement constraints that are on the land?

[00:09:47] That might be a really compelling activity to be thinking through those frameworks of how are camping laws being enforced and how maybe some of those narratives might be challenged. Like folks are saying, ‘Hey, that’s what that policy is, but that’s not really what happens.’ Or, ‘In these certain areas, this is where it’s different.’

[00:10:06] Thinking about the physical space and how that might be being used, I think, would be really compelling and kind of thought-provoking for students who may not have the exposure to what life is actually like when you’re trying to find a place to live.

[00:10:18] Solmaz Kive (UO): I agree. That’s a great idea. So both exposure to the lived experience but also connecting the city policies to the form of the design. I think that’s a great idea.

[00:10:29] Blake Burrell (Human Rights Commission, HAPWG): We had a lot of discussions in our working group about prohibited camping ordinances expanded with House Bill 3115, how that impacted people’s interactions, for example, sleeping in spaces that are deemed waterways, so like your proximity to a creek or a river, and then people’s ability to reside near public or educational institutions like the library or schools.

[00:10:54] So those are big design elements that I think looking at what types of things are connected to those different aspects of the city landscape would be, I think, really compelling and something that we could organize experience around.

[00:11:10] Solmaz Kive (UO): I agree. This is a great idea. It works from different aspects. So it works in terms of relating the furniture—if you think of something like boulders or benches as furniture—and they’re relating that to the architecture, library, schools, things like that. And then you have the level of policy. I think that’s a great idea.

[00:11:31] Jolene Bettles (HAPWG): Well, I mean there is definitely a pipeline between unhoused folks and our mass incarceration, you know, that has been going on for the last (and growing since) last several decades.

[00:11:43] One thing that does kind of catch my eye, especially around unhoused folks and how this is not just an us/them issue, but something that does impact students as well, is that (according to NPR) over 1.5 million college students in the U.S. are unhoused. And this does have an impact on academic achievement, mental health, physical health. As we all know, there is a certain trauma that happens when you lose your housing, your stability in your shelter.

[00:12:12] And that growth from that point, that healing journey is definitely not linear. You might become housed, lapse into houselessness again, become housed again, lapse into houselessness again. And I think the fallacy is that systems and people expect the linear growth and they expect it to happen soon.

[00:12:32] But as far as the University of Oregon, I don’t have those numbers, but I do know that students on campus experience housing insecurity and food insecurity as well.

[00:12:43] One activity that students could do is something that we’ve discussed on this work group prior, which is: If police are moving 200 unhoused people from a campsite, and they go to the Lane County Oregon Shelter Finder, as a good-faith effort to link unhoused people to shelter, it would be a good exercise for students to see in real time just how few beds are available in shelters. And then also explore the different ways to access those shelters, because they’re not just open 24 hours a day.

[00:13:17] Some people say, ‘Get on the waiting list.’ Some people say, ‘Show up at a certain timeframe.’ So there’s a certain amount of agency someone has to have to be able to connect to that shelter, which is why we have a lot of street outreach people who are working out in teams to try and get people connected.

[00:13:34] But that would be one way to see structurally the architecture and the systems that we’re dealing with—which is not a physical bench—but the systems that we’re working with every day to try and connect people to the appropriate resource and just how hard that is.

[00:13:50] Julie Lambert (HAPWG): The planting strips that they put down to dissuade people from laying down. They look nice, but would you consider that hostile architecture because it was done with that intent?

[00:14:03] Solmaz Kive (UO): Wonderful question. Yes, actually, that’s one of the frameworks—how hostile architecture is disguised. And to me, that’s one of the the examples of it. It looks like it is beneficial, it is beautiful, but the real intent is not really that beauty, it’s just to make it look less hostile. People who don’t think about it that way, they just won’t notice it and they appreciate that beauty.

[00:14:27] Other examples: In Seattle, I know they added a bike path. They removed one of the parking lots, one of the parkings that was used as a camping site, they removed it and they turned it in a biking path. A lot of examples of that sort of thing, yeah, it definitely includes that.

[00:14:48] Presenter: Students can also simulate the state of homelessness.

[00:14:52] Julie Lambert (HAPWG): Disconnect for 24 hours, take your cell phone and leave it home, leave your keys at home, pretend you have no friends. There’s nobody you can call and then walk around the city and try to figure out, you know, you can’t associate with your friends or anything like that. You cut yourself off completely and just put yourself in the middle of the city and try to figure out what you’re going to do, where you’re going to be and be safe.

[00:15:14] Solmaz Kive (UO): That’s a great idea. I’m thinking of it related to Jolene’s idea of taking the bus and maybe taking the bus and you don’t have your phone with you. I think that’s a great idea too.

[00:15:27] Richard Self (HAPWG): Any student can for a moment, or for as long as they can do it, pretend that they just became homeless and find out how much fun that is to navigate the system. Find out where to go eat, find out where to sleep that night, find out all of these things.

[00:15:46] And then one thing else that I’ve been thinking about for a long time, and that’s getting rid of self-interest and getting to community interest. How can we do that? This is something I don’t even know that the students could tackle or yourself, but how can we change this from a self-interested community to a community-interested community?

[00:16:11] Blake Burrell (Human Rights Commission, HAPWG): I look forward to seeing ways that we can support their work and hopefully get some recommendations. We haven’t really produced any planning-based recommendations from this work group. We advise a lot on policy and organizational matters, but some of those environments that are really important for us to be making recommendations really is in the planning department.

[00:16:33] So I’m hoping that this kind of a compelling conversation that turns our wheels on how we might make recommendations in the planning space and students might be able to identify themes in planning practices that we would want to communicate as falling into this definition of harmful or hostile.

[00:16:52] So thanks for the engaging dialogue and I hope we can do something really meaningful with their work.

[00:16:59] Presenter: A Human Rights Commission work group is helping UO students learn to see public spaces. They may also look at how much the city has spent on hostile architecture.

Images courtesy University of Oregon and Tdorante10, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.