Logging, lawsuits, and lost revenue: The fight over Oregon’s state forests

7 min read

by Rep. Cyrus Javadi

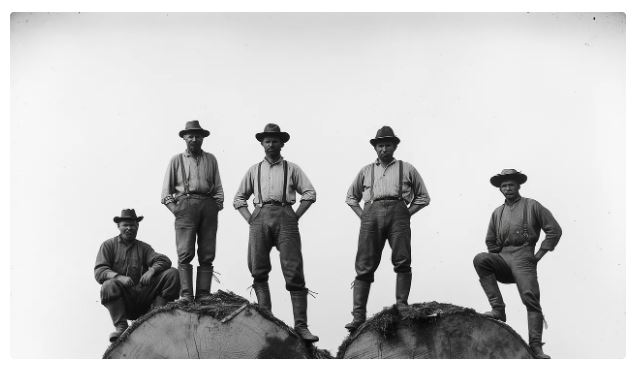

Let’s start by imagining you’re a county official in the early 1900s, sitting behind a creaky wooden desk, surrounded by ledgers so grim they could double as Edgar Allan Poe manuscripts. You’ve just inherited acres of tree stumps—forests that were once lush but have now been logged into oblivion by a bankrupt timber company. Taxes? Unpaid. Prospects? Looking dim.

Then, the state of Oregon strolls in, flashing a deal: “Hand over these cut-over lands, we’ll fix them up into real forests again, and you’ll get a cut of the timber revenue once they’re producing.” It sounded like a win-win, a bit like trading a busted jalopy for a vow that someday you’d get a sleek new car.

Flash-forward a few generations, and suddenly, that deal is being quietly reworked through something called the Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP). Now, counties that depend on timber bucks for things like schools and road repairs are feeling more than a little whiplash.

To understand why House Bill 3103 has folks fired up, we need a quick detour into how these state forests came to be—and why the original “You get the revenue, we handle the forests” handshake is starting to feel a tad shaky.

The origins: When counties handed over their lands

Back in the roaring timber days, Oregon’s coastal forests were the place to be: sawmills humming, logs floating down rivers like a conveyor belt of future houses, and entire economies fueled by wood. Then came the Great Depression, bankruptcies, and counties stuck holding a bag filled with unpaid taxes and ground-down tree stumps.

Enter the State of Oregon, stage left, with a pitch: “Transfer these lands to us. We’ll manage them as ‘working forests,’ and we’ll cut you in on timber revenue.” And that’s exactly what happened. Starting in the 1930s, counties offloaded thousands of acres of virtual wasteland, trusting the state to replant and eventually turn them back into booming forests. By the 1950s and 60s, those once-barren slopes were flourishing again, and counties were reaping timber revenue to pay for roads, schools, and local services. It was about as close to a happy ending as any government arrangement can get.

The state’s promise: Timber revenue for communities

Lest anyone think the counties were being freeloaders, it’s worth noting this was never a gift from Salem. Those lands originally belonged to the counties. The state was effectively a steward—committing to manage them for future harvest and send the proceeds back home. And for decades, the system chugged along well enough that most folks barely questioned it.

The shift: From working forests to off-limits habitat

But then, environmental awareness revved into high gear in the 1990s, courtesy of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and an array of legal battles that made the final season of Game of Thrones look downright peaceful by comparison. Protecting species like the northern spotted owl, coho salmon, and the marbled murrelet (yes, that’s a real bird, not something Dr. Seuss dreamed up) meant tighter logging restrictions. Counties that were counting on timber revenue suddenly saw the spigot slow to a trickle.

Now, responsibly managing a forest isn’t exactly akin to strip-mining it. Most county officials understand that if you burn through your natural resources with zero concern, you’ll eventually be left with empty pockets and angry owls. But the pendulum seemed to swing from “working forest” to “off-limits nature preserve,” and local communities felt the pinch when timber harvest levels fell dramatically—putting that original handshake agreement on the back burner.

Why adopt an HCP? The state’s motivation

Fast-forward (again) to a big, fancy lawsuit. Environmental groups argued that Oregon’s logging practices amounted to an “illegal take” of protected species under the ESA—particularly the marbled murrelet. Instead of going 12 rounds in court, the state decided on an Habitat Conservation Plan: a kind of get-out-of-lawsuit-free card if you meet strict conservation commitments.

Timber folks initially breathed a sigh of relief, thinking, “Okay, at least now we’ll have some regulatory stability.” But the relief turned to nail-biting when the projected annual harvest levels got slashed from historic estimates of 225–250 million board feet (imagine enough lumber to build a solid stack of suburban neighborhoods) down to as low as 165 million in some proposals. If you’re more of a visual person, think of it this way: going from 250 million to 165 million board feet is like planning a feast and then realizing half your guests aren’t getting any pie.

And here’s a plot twist worthy of a Netflix docuseries: these forests actually produce, in total, between 800 million to a billion board feet of new growth each year. Historically, harvesting in the 225–250 range never came close to jeopardizing sustainability, because the forest grows back. It’s not like the trees take personal offense and decide never to show up again. Yet, the state piled on extra conservation measures, including species not even listed as endangered yet (if that sounds like planning your own retirement party at age 22, you’re not alone in scratching your head).

The consequences: A crisis for Clatsop and Tillamook

Counties like Clatsop and Tillamook have historically depended on the revenue funneled through the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF). Roughly 60% of state forest money went to these “trust land” counties, while ODF itself took about 37%. Now, with potential harvest levels in free fall, ODF’s own figures suggest that local communities could lose up to $18 million annually. That’s the kind of budget shortfall that can cause police departments to hold fundraisers just to gas up patrol cars—or force schools to shorten their week just to stay afloat.

And for many, the kicker is that the new HCP might not be the environmental victory parade it’s chalked up to be. Instead, it looks more like a bureaucratic blockade that’s tossing an 80-year-old agreement into a dusty file cabinet marked, “We’ll get to this eventually.”

The work that has been done since taking office

Since taking office, I’ve logged (pun intended) more hours than I care to count in meetings with State Foresters, conservation groups, local law enforcement, loggers, and anyone else who has a stake in Oregon’s timber economy. There have been tours through state forests to see firsthand how these policies land on the ground (spoiler alert: it’s rarely as tidy as it looks on paper), plus a parade of public testimonies where frustration boiled over like a pot left on the stove too long.

The aim? To get Oregon’s Department of Forestry to adopt a balanced HCP that respects both environmental laws and the longstanding economic needs of rural communities. Easier said than done.

HB 3103: A call for transparency, accountability, and predictability

Enter HB 3103, co-sponsored by me, Rep. Mark Owens, and Sen. Suzanne Weber. Contrary to rumors, this bill doesn’t demand a “do-over,” nor does it propose re-enacting the logging free-for-all of yore. Instead, it insists on a few key virtues many bureaucracies claim to love but sometimes forget: transparency, accountability, and predictability.

Specifically, HB 3103 aims to ensure that:

- The Oregon Department of Forestry sets and sticks to sustainable harvest levels based on real growth data.

- Counties can rely on these levels for budgeting, instead of finding out at the last minute that funds have evaporated.

- There’s a clear path to recourse if ODF moves the goalposts again without justification.

Meanwhile, the current version of the HCP is off in Washington, D.C., awaiting federal approval. If it gets the thumbs-up, Oregon lands a safety net against ESA lawsuits, but local communities worry that the “footprint” of the HCP could keep expanding—especially with new species waiting in the wings.

In plain English, HB 3103 says: “Fine, we’ll work within the HCP, but let’s make sure no one’s blindfolded while they do it.”

The bigger picture: A fight for rural Oregon

When rural economies get kneecapped by policy decisions made hundreds of miles away, you can bet there’s going to be pushback. These counties bet big on a partnership with the state decades ago, counting on the revival of clear-cut wastelands into productive forests. Now, they’re watching newly minted policies shrink harvest volumes below even the naturally replenishing growth rate. If that’s not a head-scratcher, I’m not sure what is.

At its core, this debate is about whether Oregon is going to honor the spirit of the original land transfer. These forests were never meant to be locked behind red tape, nor were they meant to be ravaged. They were supposed to be managed sustainably for both habitat and harvest. HB 3103 is a polite-yet-firm knock on the door, reminding state agencies that the handshake with counties isn’t some relic to be tossed aside.

Because if we let this slide—if we allow an 80-year-old promise to get buried under ever-expanding restrictions—then we have to wonder: what other promises are at risk of quietly vanishing from Oregon’s political landscape?

In short, we’re not asking for a time machine back to the freewheeling logging days of the early 1900s. We’re asking for the transparency, accountability, and predictability that any decent steward of the forest—and of a century-old agreement—should be providing.

© 2025 Cyrus Javadi, 1010 Main Ave, Tillamook, Oregon 97141. All rights reserved. Republished with permission. Subscribe to his newsletter, ‘A Point of Personal Privilege,’ at https://cyrusjavadior.substack.com/.