UO ‘Frohnmayer model’ had a good run

5 min read

by Marty Wilde

When he took office in 1994, UO President David Frohnmayer had a budgetary problem. The voters passed Measure 5 in 1990, limiting property taxes and forcing the state to reallocate general fund support away from higher education. State government support for UO’s budget had dropped from around 60% to about 45%.

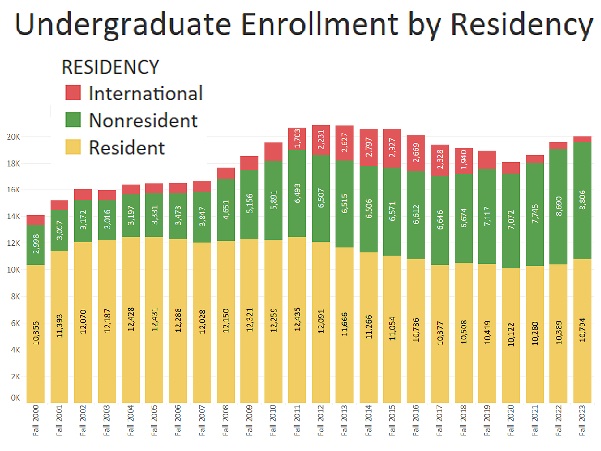

Oregon had always attracted some out-of-state and international students, and they typically constituted about a fifth of the total undergraduate enrollment. UO was primarily an institution that educated in-state students, but the state subsidy for that task was diminishing. With the decline in state support, something had to change.

Balancing the books with nonresident students

Looking to UO’s strengths, Frohnmayer saw that that UO could compete effectively for out-of-state and international students if it improved its standing in the increasingly-important college rankings and leveraged its Nike-supported athletics.

UO sought to attract well-prepared, relatively wealthy California students who hadn’t made the cut at the top tier of UC schools and didn’t want to go to CSU campuses. California voters passed a prohibition on race-based admissions to its public universities in 1996, which led to a substantial increase in the percentage of Asian students at UC schools and drove non-Asian students to other institutions, including UO.

UO also benefited from Chinese social and governmental policies that supported sending students to U.S. institutions. UO encouraged this through investment in the American English Institute and other programs to support international students.

UO’s efforts largely succeeded, boosting out-of-state and international enrollment to almost 50%, with most of these students paying full freight. This balanced UO’s budget, despite the decrease in state funding to a level below 20%.

The Frohnmayer model held up relatively well until the late 2010s. State support stabilized just below $10,000 per student. In-state tuition fell to between $10,000 and $15,000 per year, subsidized by out-of-state and international tuition ranging from $25,000 to $30,000. (Dollar figures are normed for a more accurate comparison.) International student enrollment peaked at around 13% of the undergraduate student population.

Live by the sword, die by the sword

However, by the late 2010’s, the trends that supported this success started to reverse. China had refocused on keeping its students in China. Undergraduate enrollment at the University of California had also climbed, from below 150,000 to over 250,000.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, it strengthened the “stay close to home” trend, observed in a decline in California students at UO. International student enrollment at UO dropped below 2%. UO continued to fight hard to recruit out-of-state students, increasing their numbers from just over 7,000 in 2020 to almost 9,000 in 2024. But recently UO has started to miss out-of-state enrollment targets, driving in-state tuition to almost $17,000 and nonresident tuition to over $43,000 to pay the bills. In Oregon, state support per in-state student remains low compared to other states.

The crisis is here

The Trump administration’s attacks on immigration, China, research funding, and student loans have deepened the cracks in the Frohnmayer model. UO President Karl Scholz faces an unenviable task—leading the university away from a model it has relied on for 30 years.

To receive more state support, UO would have to shift from its liberal arts focus, copying the strategy adopted by Oregon Institute of Technology and (to a lesser extent) Oregon State University by pushing students toward more remunerative and practical fields.

Oregon Institute of Technology achieved a ranking as the top-rated “value-added” public university in the country by recruiting smart kids from families of modest means and graduating them through practical degree programs that are run efficiently.

UO repeats this technical focus with the Knight Campus and UO’s Colleges of Business and Education have always emphasized practical skills. A shift toward degrees with more focus on workforce needs would allow some increase in tuition as well, to the extent that students entering more lucrative fields may be more willing to spend (and borrow) more money.

Another approach could be to broaden recruitment in India, which currently is ranked second in the number of international students at UO, and Malaysia, two countries that focus on English language proficiency and have increasing U.S. investments.

However, the Trump administration’s fight to strip Harvard of its international students threatens this approach by showing that the U.S. is not a reliable international partner in higher education. UO could also focus more on recruiting out-of-state students from other Big Ten states, with an eye toward finding markets facing challenges similar to those in California in the 90’s.

Two approaches definitely won’t work. First, doubling down on the liberal arts focus will only worsen the problem. The value proposition for a university degree is under active attack. Two examples: UO’s second most popular major is psychology, but only 15% of psychology undergraduates go on to graduate school in psychology and UO graduates almost 200 political science majors, but only 20-30% go on to graduate studies.

While UO has increased its focus on workforce skills, it has resisted more concrete steps to respond to workforce needs. For instance, proposed expansion of the legal studies minor—the most popular on campus—into a major that would lead more directly into law school or professional paralegal practice was recently blocked out of concern that it would eat into the number of political science majors.

I don’t suggest that students should not study what interests them, but a university that wants to succeed should require that students commit and adhere to a program of study with a clear and realistic employment or graduate studies goal within a reasonable time of enrolling. It should not prioritize protecting legacy programs from competing with programs that meet workforce needs.

Second, recruiting more in California and China won’t balance the budget. The trends that challenge the Frohnmayer model there are unlikely to reverse anytime soon. China has been quite explicit in its desire to improve its own higher education system and keep more of its students in China. Similarly, the UC system continues to expand to meet demand within California, as a public university should.

UO gets some criticism for administrative bloat and “platinum-plated” athletic facilities. However, form follows function to some degree. The Frohnmayer model used these to attract the students UO needed to succeed—wealthier nonresident students who could subsidize in-state students.

Turning away from that model will allow greater efficiency and refocusing of some of those investments. Determining where those investments should go requires the kind of leadership I hope President Scholz will show.

Marty Wilde represented central Lane and Linn counties in the Oregon legislature. For more of his Letters From a Recovering Politician, subscribe at https://martywilde.substack.com/subscribe.