Opinion: Fear will not fix homelessness

3 min read

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

by Sarah Koski

It’s absolutely true: We all want safer streets and a healthier city. But those goals should never come at the expense of our most vulnerable neighbors. As the Eugene City Council and Eugene Police Department consider policies that could further criminalize homelessness, we must tell the truth about who is most at risk—and what it says about our community when poverty becomes a crime.

Here’s the reality: People living outside face far higher rates of violence and early death than the housed public imagines, yet the narrative too often centers on the danger they supposedly pose rather than the harm they endure.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness tracks national trends and reminds us that homelessness is rising in many communities not because people choose to be outside, but because housing is scarce and costly, services are stretched, and safety nets are weak. Their 2025 State of Homelessness overview shows growing demand for shelter, health care, and stabilization supports across the country.

Oregon illustrates these realities with painful clarity. The 2024 Hate Crimes Report by the National Coalition for the Homeless found that Oregon accounted for 29.8 percent of all fatal attacks on people experiencing homelessness nationwide between 2020 and 2022, the highest share of any state.

The report describes Oregon as having (quote) “the highest levels of violence against people who were unhoused we have ever documented.”

Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Domicile Unknown report also found that 456 unhoused people died in 2023 in Multnomah County alone, the highest number since tracking began. People experiencing homelessness in the county are 18 times more likely to die from homicide or suicide than the general population. Their average age at death was just 46.

Violence is not limited to Oregon. National research shows that homicide, overdose, and injury deaths among unhoused people have tripled over the past decade, reflecting what the NAEH calls a national emergency in human rights and housing.

And let’s not also turn away from sexual violence. NAEH has long noted that traffickers target people who are poor, isolated, and without stable housing. A National Center for Missing and Exploited Children study found that an estimated 19% to 40% of youth experiencing homelessness become victims of sex or labor trafficking. Another national survey published by United Way found that 64% of trafficking survivors reported homelessness or housing instability at the time they were recruited.

The takeaway is not despair. It is urgency and course correction.

When leaders prioritize encampment removal, displacement, and hostile architecture, they may make homelessness less visible, but they do not make people safer.

The data points in a different direction: Expand low-barrier shelter and permanent housing, scale treatment and harm reduction, place peer navigators where crises occur, and stop criminalizing survival. Fear creates headlines. Facts save lives.

Sarah Koski shares compassionate reporting on the intersection of transit and homelessness at Eugene’s Homeless Heartbeat.

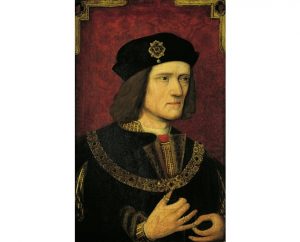

Image: Sarah Koski wears a mask in many of her photos to represent the faceless work she does helping the unhoused and the anonymity of lost souls on the street. The black balaclava and shadowed hoodie mirror the stereotypes often projected onto people living outdoors: safety gear becomes “suspicious” and survival becomes a “threat.” Against a wall of burning red, the subject meets the viewer’s gaze, challenging them to confront the reflexive fear that shapes our policies, policing, and compassion. For Sarah, this photo attempts to hold a mirror to a culture that too easily confuses poverty with danger.