Mark Robinowitz: Where were environmental groups on highway widening projects?

9 min read

Mark Robinowitz: I’m Mark Robinowitz, and I am a ‘ Road Scholar’ that has been involved with transportation policies and preventing freeway expansion since the 1990s.

[00:00:16] The largest highway transportation project planned in Eugene through the remainder of the petroleum age is the massive widening of Beltline Highway, which was approved about two years ago by the Federal Highway Administration and the Oregon Department of Transportation.

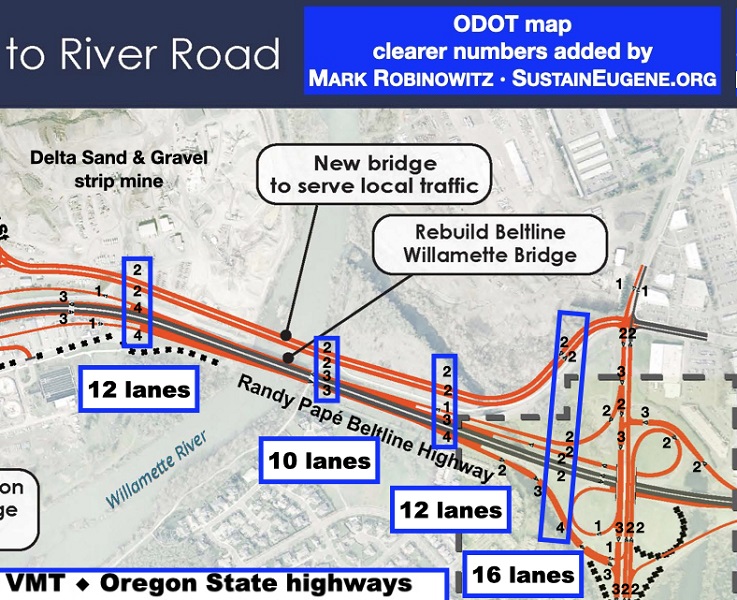

[00:00:39] This involves replacing the freeway crossing of Willamette River just west of Delta Highway. Currently, it’s four lanes, and the proposal, as approved, would expand the crossing to between 10 and 16 lanes just west of Delta Highway.

[00:01:01] This would involve a six-lane total bridge of the mainline highway, and a four-lane local arterial expressway for shopping mall traffic between North Eugene on either side of the river—River Road neighborhood and the Delta Highway neighborhood.

[00:01:24] This is an example of Californication. It would be as large of a highway as anything in the Portland metro. And going further south, you would have to go to the San Francisco area or Sacramento to find a highway of comparable width.

[00:01:44] To be fair, the Beltline Highway in this area is the busiest road in Lane County. It is actually busier than any location on I-5 in Lane County, and it’s a mess. Everybody wants to use the road at the same time in the morning or the same time in the afternoon. Of course, it gets busy. But this scale of highway widening is not to deal with current traffic problems.

[00:02:15] It is a massive subsidy of a third of a billion dollars or more to the real estate speculation industry, which is simultaneously pushing an expansion of the city of Eugene to connect to the city of Junction City. That is a project that was approved by the city and Lane County roughly two years ago.

[00:02:42] I attended the public hearings for this that the planning commissions and then the elected officials had, and the environmental groups, which are fabled to exist in Eugene, curiously were absent. And it was rubber-stamped by all of these bodies, with virtually no dissent. It’s called ‘urban reserves,’ and this is the real purpose of the Beltline expansion.

[00:03:11] The Beltline expansion also is free from any of the environmental groups of the area publicly suggesting this is a bad idea: overkill, unnecessary, polluting, overpriced. None of these types of concerns are echoed by our environmental legal eagles, by our fabled climate groups, environmentalists, bird watchers, butterfly aficionados. They are all AWOL on the Beltline widening. even though this would facilitate more paving of farmland, overdevelopment, it’s massively polluting, and it would lock in for the rest of the oil era potential for massive expansion of highway traffic.

[00:04:07] One of the climate groups told me they’re just concerned about electric vehicles and more buses, so they weren’t going to take a stand on the Beltline widening. I had attorneys tell me that it’s not the role of environmentalists to oppose freeway construction, which is news to me. I’m not an attorney, and I don’t play one on TV, but I do know that some of the most contentious environmental legal struggles of the past half century have involved highway projects.

[00:04:43] My favorite environmental law, Section 4(f) of the 1966 Transportation Act, actually was ruled on by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971. 4(f) says you can’t build highways through parks if there’s a prudent and feasible alternative, and that was in a different era of the Supreme Court, but it was one of the most significant environmental decisions of the Supreme Court in its history, not just on transportation, but on any environmental concern.

[00:05:19] It’s the strongest environmental law that we have because it does not require merely disclosing the damage. It actually requires that damage be prevented. The Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, Endangered Species Act, rules on national forests, many others, they merely require that the damage be disclosed, which is not the same as preventing the damage in the first place.

It was the main law that prevented a previous paving project in Eugene, the West Eugene Parkway, first proposed in 1951 (that’s not a typo). The highway was withdrawn in 2007, cancelled by the Federal Highway Administration, which realized they were going to lose a federal lawsuit because the project was so illegal, and there was no construction money for this $200 million project.

[00:06:28] Only $17 million had been appropriated, and highway construction companies don’t work on credit. They want to be paid in real time. 4(f) was the main law that stopped this, since there are nature preserves in the path of the Parkway in the West Eugene wetlands. A common misconception for the Parkway is that wetlands were the legal obstacle that prevented the project, but wetlands can be paved over, according to the Clean Water Act, if mud pits elsewhere are created as compensatory mitigation,

[00:07:13] Whereas 4(f), which prevents paving of parklands, is considerably stronger than the Clean Water Act. It’s not perfect, but it is the strongest environmental law, and it has stopped more highway projects than any other federal law over the last several decades.

[00:07:34] Unfortunately, 4(f) does not apply to the Beltline Highway approval since there are no formal parks in its path and the wetlands that are in the path of the Beltline widening are very small, not ‘high quality.’

And since the project was approved more than six months ago, you can’t even sue anymore. That is one of the constrictions on the legal process that the Republicans in Congress put in about a decade and a half ago.

[00:08:13] It used to be that you could sue at any time after approval, but transportation departments got tired of people suing, so now it’s very difficult. You have to sue immediately or you lose standing to sue it all.

[00:08:28] Another project that was also approved about two years ago is widening of Highway 126 west of Eugene to just east of Veneta across the lake of Fern Ridge Reservoir. This is also a highway project that have some design issues. People go very fast, faster than they should. Aggression and gasoline is a bad combination. So there are accidents at times, and the road is lacking a wide shoulder if someone has a flat tire or other mechanical difficulty.

[00:09:08] But instead of choosing a safety option, which was studied in the environmental assessment, ODOT picked widening it to five lanes. And this is not only for safety, although safety was the excuse, but it’s a $200 million project to further the expansion of the city of Veneta as a bedroom community, but without adding extra public transit for people to go back and forth from Veneta to their employment in Eugene or Springfield.

[00:09:45] And this is what the purpose of many transportation projects is. They work hand-and-glove with the realtors and developers and speculators. So the transportation people arrange the transportation projects without which you would not be able to build an expanded neighborhood.

[00:10:06] This is not unique to Eugene and Lane County. This is everywhere.

[00:10:10] Another project consideration for the Beltline Highway is the freeway bridge over the Willamette River on Beltline is nearing the end of its service life. It was built in the 1960s before anybody knew about the Cascadia Subduction Zone and it is the last major highway bridge in Eugene over the Willamette that was not strengthened or replaced in anticipation of a large earthquake in Eugene that will damage structures.

[00:10:47] But replacing a bridge with much wider structures is expensive. And it makes it difficult for the region, for the state, to adequately address all the damaged bridges that we have. We have log trucks that are overweight that are causing stress on bridges.

[00:11:12] We have bridges that were built in the 50s and 60s that no longer have structural integrity, and of course we have the looming threat of the subduction zone, which is impossible to predict when it will happen, but it is a certainty that at some point it will happen.

[00:11:29] So if we replaced bridges with bridges of equivalent width, we would have more financial and physical resources to address the backlog of troubled bridges over water.

[00:11:45] When the parkway was canceled in 2007, I had hoped that that would be a catalyst to rethink the region’s long -term transportation and energy plans.

The highway would have bisected a important federal nature preserve, the West Eugene Wetlands Project, but that was not my only motivation for being deeply involved in helping prepare a federal lawsuit to prevent the project and raising attention in the community that this was an urgent concern.

[00:12:25] I was also concerned that transportation expansion is a commitment to increase energy use at a time when our main transportation energy sources, the Alaska pipeline and fracked natural gas, are in irreversible decline since fossil fuels are not only polluting, but they are also finite and depleting. The Alaska pipeline has declined more than three-fourths over the last 35 years since 1988, when it peaked. And for electricity, our largest energy source in the western power grid is natural gas, not hydropower, unlike EWEB’s sweet lies that they tell the public. And natural gas is experiencing a surge due to hydraulic fracking. But this is a short-term boom, and when the fracking sputters, we will likely see sharp declines in the availability of natural gas.

[00:13:37] This is a reason not to support electrification and electric cars and electric everything, but to reconsider how we can reorient everything for hyperconservation: Relocalization of ourselves, relocation of production, and generally anticipate that the earth is abundant and finite.

[00:14:04] Some people think the earth is flat, but an equally ridiculous concept is the earth is getting constantly bigger and endless growth is possible physically on a finite planet. In reality, the earth is abundant and finite.

[00:14:23] And we need to have our transportation and land use policies and every other policy based on the idea that Spaceship Earth is all we have. We’re not moving to Mars. We’re not having another planet give us new resources to exploit. The age of imperialism is over and conquest, and we have to learn how to share the only home that we have.

[00:14:55] So how this relates to transportation policy is cancellation of the West Eugene Parkway canceled that particular project. ODOT sold off some of the parcels of land in its path, which is always a good clue that the project is not coming back. But unfortunately, that did not spur a substantive shift in the region’s transportation and energy policies.

[00:15:24] Some of the transportation advocates (and this is also, again, not a Eugene-only problem) have a bit of regulatory capture where they’re chummy with the governmental transportation planners, and they are hesitant to call for deeper systemic changes that would make their goals easier to recommend and implement. And a test of their lack of sincerity is the total absence of any pushback from grassroots transportation advocates for even just calling attention to the Beltline widening project.

[00:16:12] And if you look on the city of Eugene’s website, you will not see any mention that the Beltline widening was approved about two years ago. In fact, ODOT didn’t even want to post anything about their decision online until I called up the project manager and asked why there is no mention on their website that it had been approved.

[00:16:39] Now there’s a mention, not that it really matters because nobody seems to care that we’re going to do this massive expansion. But it is limited only by the unavailability of funds. And just like with the (Highway) 126 project, if the state legislature or Pete Buttigieg or the Tooth Fairy come up with a half a billion dollars, then construction can begin on these two projects.

[00:17:15] The final point is: In the federal lawsuit that would have been filed against federal highway administration if the West Eugene Parkway had been approved, it was not just Section 4(f) as well as Clean Water (Act), Endangered Species (Act), and other federal violations.

[00:17:40] I also hoped to have a new legal option. Under federal transportation law, a federal approval of a highway project is not for current traffic levels, but to address traffic problems 20 years in the future. And while it’s anyone’s guess what traffic levels will be 20 years from today, the assumption of the planners is that it will always keep going up.

Well, I have occasionally run into Transportation planners for governments who quietly admit that they understand this, but they’re not allowed to say it in public because it’s a bummer to suggest that the American way of life might have an expiration date built into it.

[00:18:34] So transportation is a stand-in from larger concerns about the future of civilization that we need to address to mitigate the downslope, to reorient everything to be hyperefficient. We’re damned if we drill because of pollution, including climate change. We’re damned if we stop because concentrated finite fossil carbon powers everything, and we’re damned as it runs out because we’re totally unprepared.

[00:19:12] I have an archive of transportation advocacy in Eugene and Lane County at sustaineugene.org and transportation policy generally at peaktraffic.org.