Report: 2023 was driest year for global rivers

7 min read

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

from the World Meteorological Organization

The year 2023 marked the driest year for global rivers in over three decades, according to a new report coordinated by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which signaled critical changes in water availability in an era of growing demand:

- 2023 was driest year for global rivers in 33 years

- Glaciers suffer largest mass loss in 50 years

- Climate change makes hydrological cycle becomes more erratic

- Early Warnings for All must tackle water-related hazards

- WMO calls for better monitoring and data sharing

The last five consecutive years have recorded widespread below-normal conditions for river flows, with reservoir inflows following a similar pattern. This reduces the amount of water available for communities, agriculture and ecosystems, further stressing global water supplies, according to the State of Global Water Resources report.

Glaciers suffered the largest mass loss ever registered in the last five decades. 2023 is the second consecutive year in which all regions in the world with glaciers reported ice loss.

With 2023 being the hottest year on record, elevated temperatures and widespread dry conditions contributed to prolonged droughts. But there were also a significant number of floods around the world. The extreme hydrological events were influenced by naturally occurring climate conditions – the transition from La Niña to El Niño in mid-2023 – as well as human-induced climate change.

“Water is the canary in the coal mine of climate change. We receive distress signals in the form of increasingly extreme rainfall, floods and droughts which wreak a heavy toll on lives, ecosystems and economies. Melting ice and glaciers threaten long-term water security for many millions of people. And yet we are not taking the necessary urgent action,” said WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo.

“As a result of rising temperatures, the hydrological cycle has accelerated. It has also become more erratic and unpredictable, and we are facing growing problems of either too much or too little water. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture which is conducive to heavy rainfall. More rapid evaporation and drying of soils worsen drought conditions,” she said.

“And yet, far too little is known about the true state of the world’s freshwater resources. We cannot manage what we do not measure. This report seeks to contribute to improved monitoring, data-sharing, cross-border collaboration and assessments,” said Celeste Saulo. “This is urgently needed.”

The State of Global Water Resources report series offers a comprehensive and consistent overview of water resources worldwide. It is based on input from dozens of National Meteorological and Hydrological Services and other organizations and experts. It seeks to inform decision makers in water-sensitive sectors and disaster risk reduction professionals. It complements WMO’s flagship State of the Global Climate series.

The State of the Global Water Resources report is now in its third year and is the most comprehensive to date, with new information on lake and reservoir volumes, soil moisture data, and more details on glaciers and snow water equivalent.

The report seeks to create an extensive global dataset of hydrological variables, which includes observed and modelled data from a wide array of sources. It aligns with the focus of the global Early Warnings for All initiative on improving data quality and access for water-related hazard monitoring and forecasting, and providing early warning systems for all by 2027.

Currently, 3.6 billion people face inadequate access to water at least a month per year and this is expected to increase to more than 5 billion by 2050, according to UN Water, and the world is far of track Sustainable Development Goal 6 on water and sanitation.

Hydrological extremes

The year 2023 was the hottest year on record. The transition from La Niña to El Niño conditions in mid-2023, as well as the positive phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) influenced extreme weather.

Africa was the most impacted in terms of human casualties. In Libya, two dams collapsed due to a major flood in September 2023, claiming more than 11,000 lives and affecting 22% of the population. Floods also affected the Greater Horn of Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda, Mozambique and Malawi.

Southern USA, Central America, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru and Brazil were affected by widespread drought conditions, which led to 3% gross domestic product loss in Argentina and lowest water levels ever observed in Amazon and in Lake Titicaca.

River discharge

The year 2023 was marked by mostly drier-than-normal to normal river discharge conditions compared to the historical period. Similar to 2022 and 2021, over 50% of global catchment areas showed abnormal conditions, with most of them being in deficit. Fewer basins showed above normal conditions.

Large territories of Northern, Central and South America suffered severe drought and reduced river discharge conditions in 2023. The Mississippi and Amazon basins saw record low water levels. In Asia and Oceania, the large Ganges, Brahmaputra and Mekong river basins experienced lower-than-normal conditions almost over the entire basin territories.

The East coast of Africa had above and much above-normal discharge and flooding. North Island of New Zealand and the Philippines exhibited much above normal annual discharge conditions. In Northern Europe, the entire territory of the UK and Ireland saw above-normal discharge, also Finland and South Sweden.

Reservoirs and lakes

The inflows into reservoirs showed a similar pattern to the global river discharge trends: India, North, South and Central America, parts of Australia experiencing below-normal inflow conditions. The basin-wide reservoir storage varied significantly, reflecting the influence of water management, with much above-normal levels in basins like the Amazon and Parana, where river discharge was much-below-normal in 2023.

Lake Coari in the Amazon faced below-normal levels, leading to extreme water temperature. Lake Turkana, shared between Kenya and Ethiopia, had above-normal water volumes, following much above-normal river discharge conditions.

Groundwater levels

In South Africa, most wells showed above-normal groundwater levels, following above-average precipitation, as did India, Ireland, Australia, and Israel. Notable depletion in groundwater availability was observed in parts of North America and Europe due to prolonged drought. In Chile and Jordan groundwater levels were below normal, with the long-term declines due to over-abstraction rather than climatic factors.

Soil moisture and evapotranspiration

Levels of soil moisture were predominantly below or much below normal across large territories globally, with North America, South America, North Africa, and the Middle East particularly dry during June-August. Central and South America, especially Brazil and Argentina, faced much below-normal actual evapotranspiration in September-October-November. For Mexico, this lasted almost the entire year because of drought conditions.

In contrast, certain regions, including Alaska, northeast Canada, India, parts of Russia, parts of Australia and New Zealand experienced much above-normal soil moisture levels.

Snow water equivalent

Most catchments in the Northern Hemisphere had below to much-below normal snow water equivalent in March. Seasonal peak snow mass for 2023 was much above normal in parts of North America and much-below normal in Eurasian continent.

Glaciers

Glaciers lost more than 600 gigatons of water, the worst in 50 years of observations, according to preliminary data for September 2022 – August 2023. This severe loss is mainly due to extreme melting in western North America and the European Alps, where Switzerland’s glaciers have lost about 10% of their remaining volume over the past two years. Snow cover in the northern hemisphere has been decreasing in late spring and summer: in May 2023, the snow cover extent was the eighth lowest on record (1967–2023). For North America the May snow cover was the lowest in the same period

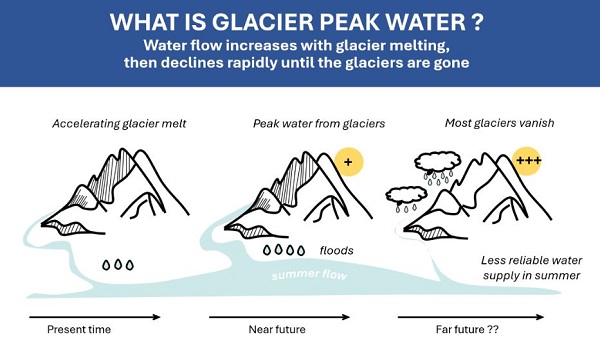

Summer ice mass loss over the past years indicated that glaciers in Europe, Scandinavia, Caucasus, Western Canada North, South Asia West, and New Zealand have passed peak water (maximum melt rate of a retreating glacier; leading to reduced water storage and availability afterwards), while Southern Andes (dominated by the Patagonian region), Russian Arctic, and Svalbard seem to still present increasing melt rates.

The State of Global Water Resources report contains input from a wide network of hydrological experts, including National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, Global Data Centres, global hydrological modelling community members and supporting organizations such as NASA and the German Research Centre for Geosciences (GFZ).

The number of river discharge measurement stations increased from 273 in 14 countries to 713 in 33 countries, and the groundwater data collection expanded to 35,459 wells in 40 countries, compared to 8,246 wells in 10 countries in the previous year (Figure 1). However, despite improvements in observational data sharing, still Africa, South America, and Asia remain underrepresented in hydrological data collection, highlighting the need for improved monitoring and data sharing, particularly in the Global South.

The report seeks to enhance the accessibility and availability of observational data (both through better monitoring and improved data sharing), further integrate relevant variables into the report, and encourage country participation to better understand and report water cycle dynamics.

Future reports are anticipated to include even more observational data, supported by initiatives like the WMO’s Global Hydrological Status and Outlook System (HydroSOS), the WMO Hydrological Observing System (WHOS), and collaboration with global data centers.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation in atmospheric science and meteorology.

WMO monitors weather, climate, and water resources and provides support to its members in forecasting and disaster mitigation. The organization is committed to advancing scientific knowledge and improving public safety and well-being through its work.