John Nichols at Encircle Films: Candidates should discuss AI, climate, justice, immigration

14 min read

If the presidential candidates won’t debate, they should at least speak in depth on key issues like immigration, the climate crisis, economic and racial justice, and artificial intelligence. So says progressive journalist John Nichols, speaking before a full house at Encircle Films Sept. 19.

John Nichols: This is a country that is in a midst of a transformation, and it is just a question of how quickly it happens and how much pushback there is against it. When countries go through circumstances like this, it tends to get very, very ugly quite often. It’s sometimes a very positive, easy arc of human progress, but more often not.

[00:00:40] The challenge you want to watch for in this period is whether one of the candidates actually figures out how to speak to the American people in a next -stage way, to deliver the message of the new era, of the next moment. And at this point we haven’t seen that yet, but there is the possibility that we will.

[00:01:01] We should have a lot more debates. And also, another thing that I find troubling is that we tend to have rallies now, but not great speeches. None of these candidates have been saying, ‘I need to deliver an address to the nation on a deep fundamental issue where I focus on one thing, don’t kind of run through the laundry list of what I want to do or what I might propose to do, but actually focus on one issue and go deep on it.’

[00:01:27] I wrote recently that I think Kamala Harris should do that on the issue of immigration. But I don’t think immigration is the only issue where these candidates, both of them, frankly, should be giving deeper, more focused addresses to reframe the debate, reframe the issues.

[00:01:40] Certainly climate crisis is something that should be discussed; our lingering economic injustice, which is simply a reality, that’s what Bernie Sanders and I wrote about; our lingering racial justice, which is so writ large across our politics and our society.

[00:01:56] These candidates should be addressing the biggest change taking place, and that is the AI revolution. The AI revolution, artificial intelligence and all the machine learning and machine advances that are associated with it, is going to be dramatically more transformational than the digital revolution.

[00:02:14] The digital revolution changed a lot. It changed so many of the ways we communicate. And it has also wiped out newspapers, by and large. So it’s totally transformed our media systems. It’s had a huge impact on our politics, not just on how candidates campaign, but also how they communicate and how they fundraise.

[00:02:33] So the digital revolution is a big deal. The AI revolution just put it on steroids, 20 times, 100 times as much change—fundamental change to our economy, fundamental change to our employment, fundamental change to how we live, fundamental change to how we communicate, fundamental change to how we deal with disease, I mean everything coming at us.

[00:02:55] And amazingly enough, there was no question on AI, no serious question on AI in the one debate that Kamala Harris and Donald Trump had. There was no question, no serious question on AI in the debate that Donald Trump and Joe Biden had. And there has been no, you know, deep, smart, serious address of this issue. They just don’t talk about it.

[00:03:18] And so we literally have one of the most fundamental changes in the history of the world taking place, a change that, by the way, when applied to military technology, could destroy the world, a change that also could, on the other side, cure many of the diseases that we’ve struggled with throughout human history.

[00:03:36] So there’s so much going on there, and it’s not being discussed. And the fundamental thing that should be discussed, of course, is the fact that we don’t have control over this radical change that’s taking place. By and large, it’s controlled by corporations as is so much else in our society. And it is a very stilted and dysfunctional politics that doesn’t recognize the major issues, the major changes that are taking place, and open up a discussion about who should be in control of those changes. And ultimately the answer is: The people should be in control.

[00:04:07] We should have democratic governance of our technological progress, democratic governance of our societal shifts, because that’s not something that you should trust to profit-seeking corporations.

[00:04:20] We had virtually no control over the digital revolution and we see the results of it, right—that we have media platforms that have been created that have created some of the most wealthy corporations in the history of the world, corporations literally with bankrolls that are bigger than the budgets of most governments around the world, generally located in Silicon Valley, and these corporations do not respond to our needs. They do not respect where we’re coming from.

[00:04:50] And amazingly enough, a very, very conservative economist, Milton Friedman, said that if you have a public good, something that society depends on—and now, of course, we have to accept that society does depend on Google, does depend to a very large extent on Facebook and other platforms—and if you have an entity that society depends on, you can’t have it monopolized by one group of very, very wealthy people, by one group of very, very powerful people, or perhaps even by one powerful individual as you have in the case of Twitter with Elon Musk and frankly many of these other companies, Facebook with Zuckerberg.

[00:05:30] And so you end up with a situation where the digital revolution created monopolies over which the people of the United States have little or no control. These monopolies have a definitional role in our politics. It doesn’t mean that they ultimately define every aspect of it, but they’re certainly immensely influential. And so we ended up in a mess of a situation. And frankly, there’s an awful lot of people who tell you that our children spend a little bit too much time on their phone. And you know, we have not just all of the political consequences, but human consequences that are that I think are very challenging for society.

[00:06:05] Now we’re coming to something that’s dramatically bigger than that, the AI revolution. And we ought to learn from the digital revolution that people need to have a lot more power, a lot more say in where things go.

[00:06:15] John Q: A question for John Nichols:

[00:06:17] Randy Prince: When you use that phrase ‘transformational effect’ talking about the digital and the AI revolution, and then you talk about journalism, well, that’s what I’d like to ask about with this election, because you’re an editor in a town that’s got a newspaper. Our town has essentially lost that. No editorial page, no letters to the editor, no local reporting, and so many other towns, so many parts of the country, news deserts. I’m wondering how much that affects this presidential election, and also civic participation in general.

[00:06:54] John Nichols: The fact of the matter is that journalism has been obliterated in the United States. The digital revolution did it untold damage. And so we have lost thousands of daily and weekly newspapers across the country, those that—really the fabric of local journalism. Even where newspapers remain, they are thin shreds of their former selves with dramatically downsized staffs. And they frankly just don’t do the job.

[00:07:18] Radio has become centralized in its ownership and defined more by streaming, often out of LA or New York, rather than a local studio. And television is essentially seven, eight minutes of weather along with six, seven minutes of sports, and then some crime coverage. It’s a mess, and you’re not getting much from it.

[00:07:38] So we see the traditional platforms for journalism in dire straits, giving us not even a minimal attempt at the level of information that we need. And then we also see new media failing to fill the void.

[00:07:54] Bob McChesney and I, a number of years ago, did a study where we looked at the number of jobs that were lost in traditional media as opposed to the number of jobs that were created in new media. And it was about a 10 to 1 ratio. You lost 10 jobs in traditional media for the one job you got in new media in actual, you know, serious journalism.

[00:08:11] So journalism is in crisis. There’s simply no question of that and it’s in its greatest crisis at the local level. Why does that matter and how does it affect the presidential race and frankly congressional races and Senate races around the country? Very simple. When you had a lot of local journalism the national debate got filtered and reframed at the local level, right? Issues that were a particular concern to a rural area were amplified.

[00:08:40] And you looked at where the candidates stood on that. The candidates, frankly, had to address those issues. So in Iowa, the Des Moines Register always brought a tremendous amount of farm coverage into the process. In Detroit, the Detroit News, the Detroit Free Press always brought a tremendous number of manufacturing, particularly auto manufacturing coverage into the process. And similarly around the country, some places, you know, you were near a military base. That was, for lack of a better term, the big industry in a particular area. And so media there covered sometimes military contracting, military weapons production in much more serious ways.

[00:09:14] We just don’t have that anymore. What we’ve got is a centralized, nationalized media coverage that is dramatically dumbed down. It doesn’t have the diversity that we used to have. Yes, we’ve got the New York Times and the Washington Post, CNN, MSNBC, fox, ABC, NBC, CBS, they’re all out there. And there are journalists who work for these institutions that do a very good job, who really, really do try. But they’re operating on the national level.

[00:09:42] They’re not operating on a local level where you can actually have a conversation, and where journalism feeds into that conversation and invites people to come back via letters to the editor, op -eds, just the general discourse of the moment, frankly, the coverage of politics and events in communities across the country.

[00:10:00] We talk about dumbing things down. We have dumbed things up to the national level to such an extent that we don’t have a little local discourse anymore. The damage to our body politic is almost indescribable. Much of the division that we have in politics today where we just literally struggle to talk to one another and people really are furious with one another is rooted in this nationalization of the debate.

[00:10:27] The fact is that instead of understanding where other people are coming from and frankly having a debate in the context of local issues, local concerns, with other people who often share those concerns, we end up in a situation where so much of the discourse is run out of Washington, out of New York, and it’s really framed by the campaigns, right?

[00:10:47] And media covers what the campaigns are doing in these broad national sweeps without ever getting really local and really engaged where people live. It’s a terrible, terrible direction that we’ve gone in.

[00:11:01] And you ask other people thinking of ways to deal with it and maybe change it. Yes, there’s a lot of folks working on it. Bob McChesney and I co-founded the group Free Press with the purpose of trying to address many of these issues. If you go to the website, you can read about a lot of the efforts to kind of open things up to renew journalism.

[00:11:20] There actually are efforts to renew journalism at the local level; there’s a great project going on in New Jersey right now. There’s a measure of hope out there. There are possibilities, but at this point what we desperately need is political leaders who recognize that this is an issue.

[00:11:35] Media isn’t just something that happens to us. It’s a part of the palette of issues that we should be addressing. We should recognize we have a crisis in journalism and there needs to be responses to it.

[00:11:48] And remember, in most countries around the world, they fund public broadcasting, community radio, community television, as well as public radio, public TV, at levels that are astronomically higher than the U.S., sometimes an 80 to 1 ratio. The amount of public funding for media is so dramatically greater than the U.S. that you really, you struggle to calculate it. And that doesn’t undermine the discourse. It doesn’t create bias. It doesn’t create a circumstance where you have an authoritarian government communicating what people should think. Quite the opposite.

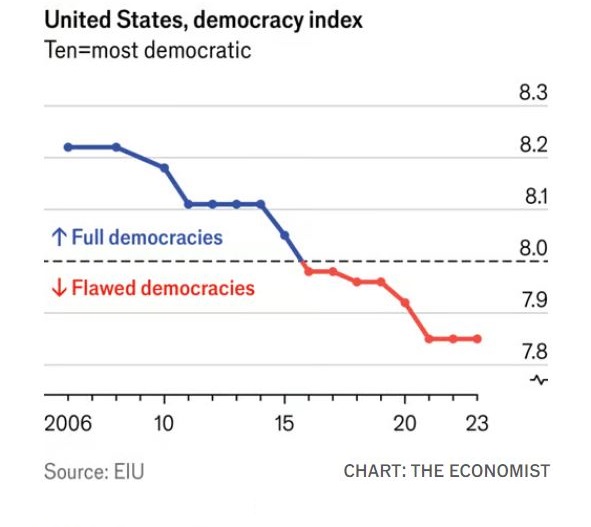

[00:12:21] The Economist Magazine’s Democracy Index finds that countries that pour immense amounts of money into public broadcasting, public media, tend to be far more democratic, small-d democratic, than countries like the U.S. that do not.

[00:12:35] John Q: The discussion followed a screening of the film, One Person One Vote? The Untold Story of the Electoral College. Another question for journalist and author John Nichols:

[00:12:45] Question: Why is it that we haven’t ever changed the Constitution? Why this reverence for the Constitution, as though this is like a religious sacred document that’s impossible to change?

[00:13:01] John Nichols: This is a really big deal. Yes, our Constitution should be amended far more. We’ve amended it a few dozen times, but generally it’s to clean up aspects of it that were so egregious that you couldn’t let them remain. We’ve also a couple times done an amendment to clean up a mess created by another amendment, as happened with Prohibition.

[00:13:18] And so we have not systematically looked at our Constitution to try and make this country more small-d democratic. That’s something that happened in much of Europe and frankly much of the world in the aftermath of World War II. Europe had been absolutely devastated by the war and so there was a lot of sort of new thinking about how to organize a society and you saw a lot of constitutional framing that was (a) progressive and (b) aimed toward making democracy functional.

[00:13:49] You also, at the same time, saw a major breaking down of colonialism, European colonialism, and so countries in Africa, Asia, other places around the world began to write their constitutions as well. So most countries have newer constitutions that are often, not always, but often significantly more small-d democratic than the U.S. Constitution.

[00:14:10] I know in America people don’t like the idea of a constitutional convention because they think it will be controlled and abused by one side of the political process and I understand that. But the fact of the matter is we desperately need to find ways to amend our Constitution in all sorts of areas. So whether it’s a constitutional convention or frankly just a moment when we pass a lot of amendments, it’s time to do that.

[00:14:33] We need to have an amendment that addresses the absolute inequality related to the U.S. Senate, we need to have an amendment that gets rid of the Electoral College, and frankly we should consider amendments to change it, as many other countries have to create basic human rights: a right to education; a right to health care; right to housing. These are not radical ideas. These are mainstream good ideas that ought to be a part of our governance and ought to be guarantees for human beings.

[00:14:59] The Electoral College is a disaster. It shouldn’t exist. It should never have existed. It was created for all the wrong reasons by leaders, a handful of white men, white property-holding men, at the founding of the American experiment who accepted the notion that Black people, for instance, would be treated as three-fifths of human beings. It was incredibly backward in their approach, incredibly destructive in what they accepted.

[00:15:28] It isn’t that the Constitution itself is overall a bad document. There are many things about it that are good: the system of checks and balances has much to recommend it; the notion that presidents can’t launch wars, but they should in fact be approved by Congress before they’re launched. There are many things in the Constitution you could find that are appealing, and there are many of the amendments that have made it better.

[00:15:46] But at the heart of it is an electoral system that’s a disaster. The Senate can be controlled by a handful of small states, which are home to a minority of the population. The House of Representatives can be, and often is, gerrymandered. And the presidency is literally bartered off on the basis of an Electoral College, where you can have a circumstance where seven, eight, 10 million more people vote for one candidate, and yet the loser gets to take power.

[00:16:17] And there’s nothing about that—you can’t come up with an argument that that’s a good idea. No child that you presented that notion to would say that was fair or reasonable, and yet we’re stuck with it. We’re stuck with it because it is very, very hard to amend the Constitution.

[00:16:34] So we looked at the national popular vote, but the fact is, getting that passed through legislatures across the country is incredibly difficult because frankly, we’ve started to see resistance to it from particularly Republican legislatures around the country.

[00:16:45] And so we’re stuck with the Electoral College. What that means is that the presidential campaign is squeezed down to a handful of battleground states, usually six, seven. That’s about where we’re at right now. That’s terrible, because the states themselves help to present issues. And when you don’t go to the whole of the country, you miss out on huge numbers of issues and huge numbers of concerns around the country.

[00:17:12] Now we have a Supreme Court that is at once corrupt and biased, right, that doesn’t rule based on the facts or based on the law. This is a judicial activist majority that seeks to move things in a right-wing direction. They legislate from the bench. There is little question of that, both on social policy and also economic policy. And a host of other things, including presidential power, where they wildly irresponsibly gave Donald Trump, or any president, essentially kingly powers. So what do you do with a court that is that out of control, that is that irresponsible, that is that in contravention of our basic concepts for ethical judiciary?

[00:17:55] But it is the fact that if you’ve got a car that’s 240 years old and you haven’t done much maintenance on it, it isn’t going to run very well. And we haven’t done a lot of maintenance on our process to make sure that it runs in its best ways—fairest, most honest, most small-d democratic. And so a lot of things are breaking down; a lot of things aren’t working well at this point.

[00:18:19] John Q: John Nichols says we’ve failed to maintain our creaky old Constitution and it’s failing. It needs changes to help us bring back a local lens to political discussions and bring small-d democratic governance to emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence.