Redistricting: ‘This process is going to get wild’

6 min read

Oregonians will have multiple opportunities to comment on redistricting during September.

Chris Cobey: I’m Chris Cobey. Welcome to your crash course in Oregon redistricting. You’ve arrived at just the right time. This process is going to get wild in the next 33 days and probably beyond.

[00:00:13] John Q: The U.S. conducts a census every ten years to redraw the election maps. The 2020 census data arrived late, and Oregon faces several deadlines in September. At a training sponsored by the League of Women Voters, Dan Vicuna, from Common Cause.

[00:00:29] Dan Vicuna: What is redistricting? Every 10 years in this country, we take the census to count how many people live in the United States. And obviously when we conduct that process, we find that people have moved, people were born, people pass away, and voting districts at all levels of government from U.S. House Representatives down to state legislative districts, county, and city government, school boards, all have voting districts that may have populations that have shifted significantly.

So what we do every 10 years is redraw those districts at every level of government. The problem is, in a lot of places that process is manipulated for political advantage, and that manipulation is called gerrymandering.

[00:01:08] John Q: Dan said there are four different flavors.

Thank you for supporting

local citizen journalism

[00:01:11] Dan Vicuna: There’s racial gerrymandering, which is the manipulation of voting districts to discriminate on the grounds of race. There is partisan gerrymandering, which is typically done by the majority party and control the process in order to maximize the number of seats; there’s bipartisan gerrymandering, incumbents of both parties agree to scratch each other’s backs and make sure that they can all get safely reelected in the next cycle. And then there’s prison gerrymandering, which is the process of counting imprisoned people where the prison is located. It really distorts population numbers, instead of what we believe should be the case, is to count imprisoned people at their previous known address.

[00:01:47] John Q: Dan said Oregon law prohibits some types of gerrymandering.

[00:01:52] Dan Vicuna: Oregon does have an explicit ban against partisan gerrymandering or incumbent gerrymandering. So the language is that maps may not purposely favor any political party, incumbent legislator or other person. So of course the big question is: Are legislators obeying the law?

[00:02:08] John Q: Chris Cobey says we will find out this Friday.

[00:02:11] Chris Cobey: The next thing that’s going to happen is the big kickoff, which is Friday, Sept. 3, 8:00 a.m. The legislature is going to release the 96 proposed districts that it suggests be implemented. And so you will have a period of time over the Labor Day weekend to look at those, decide if you could do better or if you want them tweaked. And you’ll be looking for not only where your house is, but where your community, your city, your county is in the grand scheme of things.

[00:02:43] John Q: Eugene residents can testify on Thursday September 9 at 8 a.m., Friday September 10 at 5:30 p.m., and Monday September 13 at 1 p.m. and 5:30 p.m. Statewide, there are twelve, three-hour sessions.

[00:03:00] Chris Cobey: These 36 hours of hearings allow you to tell the legislature, if you have a complaint about it, or maybe you want to just say nice job. If you have a complaint about how your area or community has been handled in all three of these sets of maps, if you think it should go somewhere else, you have four opportunities to testify. There will be two for each of your congressional districts. The one you’re in, plus there are two sets at the end on Monday, September 13, at 1 p.m. and 5:30 p.m.

[00:03:33] John Q: Chris said Oregonians need to watch for political gerrymandering.

[00:03:37] Chris Cobey: The partisan politics involved here, as you may know, the Oregon legislature at the moment is dominated by one party, the Democratic party. It has solid majorities in both houses. It also has a governor who is a Democrat. The Governor has to sign the bills. If the legislature cannot redistrict, it falls to the Secretary of State, also a Democrat. And if the congressional districts can’t be drawn, that falls to five judges who submit a plan to the Oregon Supreme Court, all of the members of which have been appointed by Democratic governors. So Oregon is somewhat unique, and why the possibilities for a gerrymander exist.

[00:04:22] John Q: Eastern Oregon will probably continue to make up its own Congressional district. Norman Turrill.

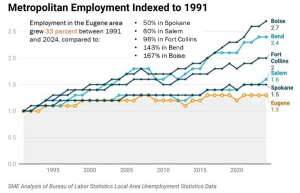

[00:04:28] Norman Turrill: The area out in the east here is actually growing a bit, but it’s only growing at about 1%, much slower than the rest of the state. One of these counties out here actually lost population. To balance that, we have Bend in the middle here that actually has been the fastest growing county in the state and the two sort of balance each other out. And so you’ll see that Congressional District Two will have not changed much from the current district.

The state has grown in population very highly around Portland in the suburbs and Portland itself has gained about 10% population. So you’ll see the other five districts squished towards the Portland metropolitan area and the rest of it is up to your own opinion as to where those lines will go.

With this configuration it’s going to be very hard for the dominant political party in the legislature to gerrymander and get their way. However, if you see that the Democrats end up with the five congressional districts and only one for the Republicans and essentially none for everybody else, then you’ll know that it’s probably gerrymandered.

Right now the largest political group in the state is the unaffiliated voters with about 40% of the registered voters; Democrats are next and the Republicans are last. You’ll see, probably, that the unaffiliated voters are virtually ignored in this process, though.

[00:06:11] John Q: It’s possible to define districts based on “communities of common interest.”

[00:06:18] Dan Vicuna: I want to dive a little into “Communities of Common Interest” because as I mentioned, we really see this as the gateway to robust public participation. We have kind of developed sort of a common definition of our communities of common interests, just kind of an amalgamation of what’s out there in other jurisdictions: a neighborhood or area whose residents have shared culture history and policy concerns, and so would benefit from being represented in the same district.

[00:06:43] John Q: For example, a district to represent all coastal communities. Chris Cobey.

[00:06:48] Chris Cobey: During the hearings this spring, some people said, ‘Well, wait a minute. Could we have a Coast Side district?’ Well, you could have a Coast Side district, but that’s about 250,000 people. Unfortunately, a congressional district takes 706,000 people. So you can’t have a pure Coast Side district. You’re going to have to nibble away and go inland. Gee, do you grab Corvallis and make that part of a Coast Side district? Do you think Corvallis thinks that it has a lot in common with Astoria, Coos Bay and other places like that? This gets into communities of interest. Should suburbanites stay with suburbanites? You know, these are the questions we’re going to think of.

[00:07:32] John Q: Citizens can tell their community’s story.

[00:07:36] Dan Vicuna: When we are doing trainings around the country about testifying about your communities, we really hope that you drive home the three C’s: culture, concerns, and count. So you know, just as it sounds: It’s how would you describe the people who are part of your community.

[00:07:51] John Q: You can also choose to submit your own maps, using ESRI software provided by the legislature. For details, see the Oregon League of Women Voters website and the slide show from the presentation.

(Update Aug. 30, 2021 1:47 p.m. to indicate that Dan Vicuna is with Common Cause, and to link to the slide presentation.)