Five years ago: Neighbors come together after the Holiday Farm Fire

11 min read

Presenter: And now, let’s listen once again to voices from the past. Five years ago at KEPW Whole Community News, we supported early recovery efforts after the devastating Holiday Farm Fire.

In the following months, neighborhood leaders organized information meetings, and prepared evacuation discussion exercises known as tabletops. Today, many neighborhoods are conducting regular radio drills, and Northeast Neighbor Andy Davis and Community Emergency Response Teams, the CERTs, are preparing for their fifth annual citywide communications exercise, coming in October.

The first to speak with the community was then-Fire Chief Chris Heppel:

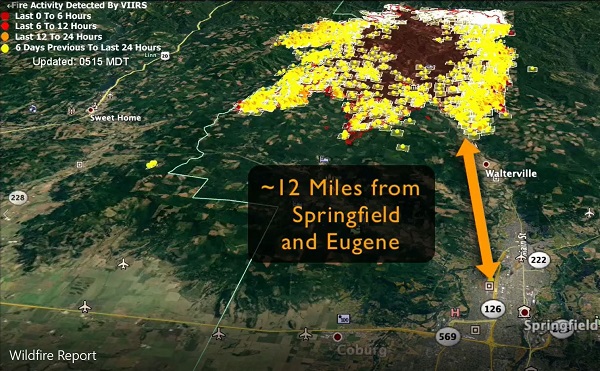

[00:00:39] Chris Heppel (Eugene Springfield Fire, chief): For me as the fire chief of Eugene Springfield Fire, the reality for me was: It can happen here. This is the wake-up call. This was the weather event that if it would’ve started, if our ignition source would’ve been in the Lowell Dexter area on that night with those same precipitating factors, we could have very easily been fighting this fire off of Spencer’s Butte, off Willamette Street, Fox Hollow. We could have very easily been into that area.

[00:01:14] Presenter: From Southeast Neighbors, David Monk.

[00:01:16] David Monk (Southeast Neighbors): The Holiday Farm Fire could have blown into the Eugene Springfield metro area. After seeing what happened in Talent and Phoenix, we had a firsthand view of a wildfire in an urban setting and realized that we needed to start organizing in our community to prepare residents for the possibility of a wildfire burning in the metro area.

[00:01:40] Presenter: Friendly Area Neighbor Tom Peck:

[00:01:42] Tom Peck (Friendly Area Neighbors): This is Oregon on September of 2020, showing fires that burned on the west side of the Cascade Mountains. Had the easterly winds continued, major metropolitan communities like Portland, Salem, Eugene, and Roseburg could have burned.

[00:02:03] Presenter: Wildland firefighter Mike Beasley:

[00:02:05] Mike Beasley: We’ll talk more about the east winds, but you can start to see that pattern here in the fire shapes in Oregon, a lot of them were in canyons that were aligned east to west, so they really picked up those east winds.

[00:02:20] The Diablo wind, the Santa Ana winds that are known by many names coming from a lot of different mountain ranges, but it’s all the same process of rapidly accelerating downslope wind. And a lot of times that comes from a dry, continental air mass that’s had a lot of sun baking it for a long time. In this case, these foehn winds picked up and took ongoing fires.

[00:02:46] Presenter: Tom Peck:

[00:02:47] Tom Peck (Friendly Area Neighbors): Strong easterly winds increased the amount of oxygen supplied to the fire. They pushed the flames towards the unburned fuel and blow hot embers or firebrands up into the air far ahead of the main fire.

[00:03:03] Presenter: Chief Heppel:

[00:03:04] Chris Heppel (Eugene Springfield Fire, chief): Reflect back, get a map and say, wow, a, a fire traveled 20 miles in 15 hours.

[00:03:17] That is just unbelievable. Not only that, it was within the McKenzie River Valley, which is, it’s a lot of green trees—they shouldn’t burn. The McKenzie River’s right there, which is a lot of humidity—it shouldn’t burn. It shouldn’t do these kinds of things. That tells us we were in a condition that it was unprecedented. Ivy burning within three inches of the McKenzie River, which is radiating humidity—Folks, that shouldn’t have happened. It should not have happened, but unfortunately that’s what we experienced that night.

So that combination of those winds ripping down the valley at 30 to 40 plus miles an hour, throwing the firebrands a half-mile ahead of the leading edge of the fire for 15+ hours, burned 20 miles and 73,000 acres.

[00:04:12] Presenter: From FUSEE, Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology, Tim Ingalsbee:

[00:04:18] Tim Ingalsbee (FUSEE): Wildfires are growing of huge size with phenomenal rates of spread, driven by these giant blizzards of embers that each one, landing in dry fuels, either in the forest floor or in a home rooftop, can ignite a new fire. And so what’s happening in these megafires is, fires are hopscotching across the landscape, leapfrogging across any kind of fire lines or fuel breaks.

[00:04:49] The reality is that even a single wildfire can threaten hundreds of homes simultaneously. So once a house in a urban cluster or community ignites, it can set up a chain reaction of house-to-house ignitions. These become the urban conflagrations that result in tragedies, disasters, catastrophes.

[00:05:12] Presenter: From the Oregon State University Extension Service, Prescribed Fire Coordinator Amanda Rau.

[00:05:18] Amanda Rau (OSU): You will find me talking about using fire to manage fire. The whole idea here is to create community resilience and being mindful about what fire might do if it comes into your community, no matter whether you live in town or out in the South Hills. All these places are the same when it comes down to it, as we’ve seen from the Almeda Fire.

[00:05:37] Presenter: Tom Peck:

[00:05:38] Tom Peck (Friendly Area Neighbors): The Almeda Fire started in Ashland as a small grass fire, which quickly spread and destroyed 2,800 homes and businesses in Talent and Phoenix.

[00:05:50] Presenter: At the Oregon legislature, testimony from survivors of the Almeda Fire.

[00:05:54] Susanna Perillat: What set in was the memory of people dying in their cars in Paradise (California). That overtook us, and there was a kind of panic about that, that I do not want to die in my car in a fire.

[00:06:10] Kathy Kali: I was the manager of the park that was the very first neighborhood to burn. So we saw the smoke coming. We got no alerts whatsoever. I literally was out banging on doors leading the evacuation.

[00:06:24] I was the evacuation because I was the only person who knew where everybody lived and where the seniors lived, and where the people with disabilities lived and where the veterans lived. And so I was out banging on doors, and then about 20 minutes into the evacuation homes in the park were burning already.

[00:06:41] James Williams: When we found out, we had six minutes to get out of our house, the flames were already in the park. We didn’t hear anything on the news. There was no warning system. There was no nothing. We lost everything we own. We walked out with the clothes on our backs. I had a flip flops, shorts, and a T-shirt.

[00:07:02] Jennie DeBunce: My housemates and I evacuated after watching the fire grow closer for hours and unable to get reliable information on the situation. Getting into our cars, I could hear propane tanks exploding.

[00:07:13] Tani Pineda: I never got a notification. I logged onto Facebook and that’s how I found out this fire. When we drive to Phoenix, my five-year-old looks at where we used to live and she asks, ‘Where’s my home?’ That just breaks me to pieces, knowing that my daughter has that memory engraved in her, that the place she called home and she grew up and she learned how to take her first steps is no longer there.

[00:07:39] Pam Halbert: I moved here July 1 to be with my aging mother. She’s 82. I’m 63, and we were combining our households when the fire struck and we lost everything. I’m sorry, this is still very emotional. I’ve been working hard. I’ve been doing all of the paperwork. And they’re running and they’re running and they’re running for assistance anywhere we can find it.

[00:08:13] For my mom and I hit my wall a week ago, so I’m very emotional. I have to apologize. Who would ever think that we’d lose everything and to face starting over at our ages. It’s very daunting and overwhelming.

[00:08:30] Presenter: From Ashland, with their Fire Adapted Communities program, Katie Gibble:

[00:08:35] Katie Gibble (Ashland, Fire-Adapted Communities): How do we help our residents, businesses, infrastructure, and everything else be prepared for wildfire and help our community recover?

[00:08:43] When support is needed, it requires working to prepare our surrounding landscapes, our forests, and our rangelands for wildfire. It involves thinking about our homes and landscaping, which is going to require providing a lot of education and outreach to the community to make that individual home work possible.

[00:09:02] And how is our landscape going to respond to fire? What’s going to happen to our hill slopes in our watershed? Becoming a fire adapted community also requires thinking about evacuation.

[00:09:12] Presenter: From Churchill Area Neighbors, Stephen Caruana:

[00:09:16] Stephen Caruana (Churchill Area Neighbors): I was heavily involved over the years in my professional life and doing post-wildfire restoration work on large Southern California fires.

[00:09:25] Mapping, GIS work, being able to look and analyze the landscape, the various impacts that can occur, and how do we then utilize that knowledge to help the people in Eugene and the neighborhood associations develop their own methods of (1) controlling areas, cleaning up areas, but also in the event of another fire, what would be the evacuation routes that people would have to take to get out of the way?

[00:09:52] This is something that’s been a sometimes difficult issue in past wildfires across the west, that how do you evacuate out of an area when there’s flames all around?

[00:10:01] Presenter: Mike Beasley:

[00:10:02] Mike Beasley: Now when you get a fire in an urban area, you can actually get an urban configuration with all that manmade material starts to burn and those are tremendous high speeds.

[00:10:14] This was clocked at 140-some-odd miles an hour, same as an F-class tornado. We can get these kinds of, uh, large fire tornadoes developing over overdeveloped areas. That’s why the home ignition zone from all that groundbreaking work that’s been done. Especially five feet from your home. Having nothing flammable and nothing organic in that first five feet is so critical.

[00:10:45] Presenter: From Eugene Springfield Fire, Amy Linder.

[00:10:48] Amy Linder (Eugene Springfield Fire): The number one susceptible part of a structure to a wildfire is the roof. So it’s the one thing, if you were to make one change to an existing structure, we would recommend making sure you have a non-combustible roof. We occasionally still see wood shakes. Those can be quite flammable, especially over time as they age and wear.

[00:11:11] So thinking about asphalt shingles or tile or metal and then making sure that your maintenance, making sure you keep the pine needles and the debris off the roof so that an ember doesn’t get in there and begin to smolder and ignite.

[00:11:27] Presenter: Katie Gibble:

[00:11:29] Katie Gibble (Ashland, Fire-Adapted Communities): In 2018, we adopted a wildfire safety ordinance, which allows us to prevent new construction and landscaping that’s going to present a fire risk.

So this includes requirements for defensible space to be created around new construction as well as additions to present properties. The ordinance also prohibits new plantings of a list of flammable plants. It requires that newly-constructed fences be constructed of nonflammable material within the first five feet of attaching to a home.

[00:11:59] And we’re actually in the final stages of adopting ordinance requiring ignition-resistant construction.

[00:12:05] Presenter: Amy Linder:

[00:12:06] Amy Linder (Eugene Springfield Fire): We have a program called Firewise that is an NFPA project. Oregon Department of Forestry is a huge supporter of that.

[00:12:13] Presenter: Katie Gibble:

[00:12:14] Katie Gibble (Ashland, Fire-Adapted Communities): Firewise program has been amazingly successful. It’s amazing. Firewise is a formal program that provides organization and direction for a neighborhood to understand and reduce wildfire risk.

[00:12:27] A neighborhood with several dozen homes or several hundred homes can organize to become a Firewise community. Ashland adopted this program early on after wildfires in both 2009 and 2010 destroyed several homes and threatened hundreds more. Ten years later, Ashland has 36 active Firewise communities. We have the highest density of Firewise communities in the country for a given town.

[00:12:55] Presenter: Amy Linder:

[00:12:56] Amy Linder (Eugene Springfield Fire): One of the questions we get asked a lot is, what is the city doing to protect our community, particularly up in the the hills? I’m going to give a huge shout out to our Public Works department in Eugene, particularly our Parks and Open Space division. They have a robust hazardous fuel treatment program for city-owned property.

[00:13:15] We think about our Ridgeline Trail and the ‘emerald necklace of Eugene’ that runs along the ridgeline up there in the South Hills. The city in a lot of cooperation with Bureau of Land Management have an aggressive plan where they are actively treating and creating fuel breaks along the ridgeline.

[00:13:33] Presenter: With programs in Ashland, Katie Gibble:

[00:13:36] Katie Gibble (Ashland, Fire-Adapted Communities): For all residents in our community, we offer one hour, one-on-one home wildfire risk assessments, and the assessment is no cost to the resident.

[00:13:44] It provides advice to an individual homeowner on not only what risk reduction actions they should be taking, but what they should prioritize, which they should be getting done first. And so that’s a really useful tool because we’re catering our advice to the individual as opposed to as one of our wildfire safety commissioners says, ‘We’re telling you to eat your vegetables,’ and it’s a boilerplate ‘We’re telling you to do this,’ and this catered experience is really important to help get risk reduction work done.

We need to get more people out there that are able to do wildfire risk assessments. And so right now we are in the process of developing a volunteer home assessor program, which will train volunteers in our community to conduct these critical assessments.

[00:14:26] We’re hoping to launch a training course this spring, just another way of further extending our ability to adapt to fire.

[00:14:35] Presenter: Amanda Rau:

[00:14:36] Amanda Rau (OSU): In the 1850s, fire was more a presence on the landscape as a management tool: a lot of savannah conditions where trees were sparse and open. These are all examples of what fire does.

[00:14:47] This is not clear cut, um, even or even age management practices. It’s not. It’s the result of fire and the people that lived with fire on the landscape.

[00:14:55] The presence of fire on the landscape reduced the hazard of fire for the people who are living here as well as providing numerous cultural benefits, foods, hunting, travel routes, countless benefits, that fire provided.

[00:15:10] Presenter: Tim Ingalsbee:

[00:15:12] Tim Ingalsbee (FUSEE): Homes can be more vulnerable to ember ignitions than big old trees. And so here we have a strategic dilemma. Should we be sending firefighters to suppress back country wildfires? Try to fight them over there so they don’t come here? Oor should be focusing more of our resources on protecting homes and communities.

[00:15:36] And as a fire ecologist, it’s pretty clear what we should be doing because many wildland ecosystems have certain benefits from fire. Forests themselves are rejuvenated by fire.

[00:15:49] They regenerate certain species of plants. The effects of fire in forests are mixed as opposed to what happens in communities. They’re almost purely destructive.

[00:16:03] Presenter: David Monk:

[00:16:04] David Monk (Southeast Neighbors): We know that many of us are ill-prepared for wildfire. Our homes are not hardened. Our landscaping is too close and too dense, so we wanted to bring this information to the larger community so that they can start preparing their respective homes.

[00:16:24] Presenter: Five years ago, neighborhood leaders came together to help share wildfire information after the Holiday Farm Fire. You can connect with others interested in preparedness through your neighborhood or community organization. For more, see the city’s website, the CERT website, and check out the evacuation tabletop exercises at WholeCommunity.News, for KEPW 97.3, Eugene’s Preparedness Works community radio.