Instead of destroying neighborhoods, use land value capture to build subsidized housing

17 min read

Presenter: At the June 25, 2025 Eugene City Council meeting, city planners suggested that councilors should remove the term ‘residential character’ from city land use code. But a longtime advocate for subsidized housing says Eugene shouldn’t follow Robert Moses in destroying communities of place. Instead, he says, vibrant cities are actually doing the opposite, and nurturing the diversity of their neighborhoods. Jefferson Westside neighbor Paul Conte:

Paul Conte: Every planning director that we worked with in the late ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s knew that neighborhoods were the key to making downtown not collapse, that our close-in neighborhoods were—I won’t say they revered neighborhoods—but they valued the neighborhoods and they wanted to make the neighborhood strong, because there was a lot of decline.

Neighborhoods are a community of place. There are other types of communities. There are work communities, there are cultural communities, there are communities of interest. One term you hear is action communities, fighting for environmental justice or whatever.

In many ways, those communities may overlap. So it’s very common, for instance, to find that a neighborhood as a community may be a community of the predominant residents, or of a particular culture.

Nobody has seemed to find difficulty with the term of ‘the Black community has some issues that they want to address’ and so on. And not so much in Eugene, but if you take a place like Portland, where there was a very robust Black community in Northeast, you see the overlap of community of culture and community of place as well as community of interest.

Neighborhoods are communities of place, but they are not exclusively that. So the idea that somehow neighborhood is an outdated concept is absurd on the face of it. Look around. Look around in Eugene. Look around at Oregon. Look around in the United States. Look around in France, in Argentina, in Mexico: Communities of place are a fundamental of existence.

The concept doesn’t go away. The question is whether you understand the dynamics, and then create policies and programs that support the things that people want in a neighborhood.

For instance, it’s pretty common that what people want in a community is they want safety, they want to be able to move about their neighborhood feeling safe, if they’re families, they may want good schools, they want education.

They also are going to want potentially different forms of quality of life. If you look at, say, the brewery district in Portland: very dense, very little green space, lots of nightlife. People live there not because they have to, but because they choose to, because that’s what they want.

Other communities have tree-lined streets and close-together, roughly single-family neighborhoods, maybe with an accessory dwelling unit, maybe with some apartments. That’s the Jefferson Westside, and people live here not because they have to, but because they want to.

But when you say that neighborhoods don’t matter, you are taking an attitude that Black communities don’t matter, Hispanic communities, Native American communities, they don’t matter. And you’re also saying that middle- and upper-income white households that want to live in compact neighborhoods, in the city center, they don’t matter. That was utterly disturbing.

Just to give you a simple example, that there are physical characters of a neighborhood: Grid-patterned streets with short blocks is a highly regarded form of neighborhood character that allows mobility, interaction, foot transportation, and so on and so on.

And the so-called ‘loops and lollipops’ of 1950s subdivisions where streets go into cul-de-sacs, streets aren’t connected and so on, that is a different character of a neighborhood.

But let’s take that as an example. So our planners subscribe to that view that, well, ‘loops and lollipops’ is a bad form because the neighborhood’s not connected. And I’m not saying it was a good plan, but the reason that developed was because cul-de-sacs enabled a semicircle of houses to watch kids on the street in a place where there’s no through traffic.

So it made every bit of sense to do it that way. And people didn’t do it that way because they wanted to exclude Black people. It’s ridiculous. What really creates exclusion in Eugene, it is very, very simple. It’s household wealth. You can live anywhere you want in Eugene if you have the money to afford it.

It’s unfortunate that poor people don’t have as many choices. Below a certain threshold of income, people don’t live where they’d like, they live where they’re forced to because of the economics, and that’s the problem we need to solve.

One of the ways we’ve done that over decades in the JWN is to take the initiative on subsidized housing developments within our neighborhood. I’m pretty sure we’re either the top or next to the top per capita neighborhood with subsidized housing. That’s what enables people to enjoy our tree-lined streets and to not have to pay extremely high prices like they would if they tried to go to the South Hills or something.

So the only exclusionary thing that’s going on in Eugene has nothing to do with the leaders of neighborhood organizations or the fact that attendance at neighborhood meetings typically is a greater proportion of homeowners than it is of renters. Has nothing to do with that.

It all is about economics. And the way you solve that is you make neighborhoods healthy, you avoid displacement, and you provide opportunities for subsidized housing. It’s as simple as that.

We can go back historically and look at the poster example of wrong-headed thinking about neighborhoods, and that’s when Robert Moses put through all the highways and bridges and destroyed neighborhoods.

Thousands of people were displaced because Robert Moses, using the power that he had accumulated, characterized them as slums and blights. He built, you know, wonderful parks, the parks under Brooklyn Bridge and so on.

So here was something that was supposed to improve the city, make it more vibrant, but the problem was, is that that all worked for wealthy people.

I don’t know whether our planners are familiar with it. They should study the history of Robert Moses and the really mistaken approach to ignoring neighborhoods and their own particular character.

And poor neighborhoods have a character, and part of that character is that they’re more affordable. And part of that character historically has been they are ill-served by public parks. So kids play in the street, but neighbors know neighbors, you know. So that is character and there is such a thing as character. It’s not just the streets and sidewalks, but is also the forms of the economics, the cultures, and so on.

And this comment about ‘neighborhoods don’t matter,’ is what they really are saying is, ‘White neighborhoods that have people who don’t like our plan are exclusionary.’ They’re not talking about Black neighborhoods. We don’t really have racial neighborhoods much in Eugene. But go to some city that has thriving Black or Hispanic neighborhoods and tell them they don’t have a neighborhood character. I mean…

The character of our neighborhood is that generally, we have compact development. There’s a pattern that occurred during the ’20s and ’30s, called front-to-rear living. We have a sidewalk that’s public space, a small front yard that is semi-public space, the house that’s private, the backyard that is semi-private.

We don’t have a lot of windows side to side. We have windows front and back. Very simple. And that physical structure enables people to live close together and be compact.

The other kind of character that you can say about the Jefferson Westside, and particularly the more westerly parts of it, is that we have shared landscape. Our backyard here has tree branches and vines that are growing in all three adjacent neighbors’ yards, coming over our privacy fences. And because we appreciate that character, we don’t go around cutting the limbs off of some neighbor’s tree coming across the yard, because we all benefit.

Now, as far as exclusionary aspects of a neighborhood, you never hear any evidence of that, right? You just hear it as a claim and disparagement of the people who live there and love their neighborhoods.

In order to get this anti-neighborhood community view to prevail, you have to denigrate the people who live there because they want to enjoy the character of the neighborhood. ‘White NIMBYs don’t want others to move in.’ The others are non-whites, renters, poor people, whatever.

These virtue signalers like to make people think that, ‘Oh, you just don’t want other kind of people here.’ No, we just don’t want crappy, destructive kinds of buildings.

I get multiple emails from people saying, ‘Oh my God, they’re putting up essentially a three-story building five feet from my east boundary of my lot. Solar is gone, my garden is gone, my privacy is gone,’ you know, and ‘I have lived in this neighborhood for 30 years and everybody is welcome to live here, but they’re not welcome to build something that ruins concrete livability.’

If you make these places so unattractive to people who don’t want some looming structure over their yard, they leave. So you get, first, you get displacement of people who have what we can call economic mobility in housing.

But the second thing that happens is where you disregard neighborhood character, and I’m talking about things like the structural requirements, the setback requirements and stuff that have been ripped apart by the deregulation of zoning, then the other thing that happens is affordable housing is being knocked down, and fourplexes and even sixplexes are being built.

And the perfect example of this and where it’s happening is neighborhoods like that area that’s south of 29th, east of Willamette, and that neighborhood used to be a swamp. And when it got built out, it got built out with large lots. So you have a low structure-to-land value and that’s near the University, it’s near Woodfield Station, so it is a very attractive area.

So what have you got there? We’ve lost one affordable house and yes, we’ve gained inventory in the higher end. But that doesn’t change the prices around there. Instead, it changes the prices up, not down, because those are built at an expensive level.

So the person who rented that house, they get displaced. Where do they go? They have to drive till they qualify, right? They have to find someplace that’s probably further out. They can’t walk to Woodfield Station, etc., etc. So you have really disrupted that type of affordable housing.

In Eugene, it’s not so much like a Black neighborhood because it’s more in terms of economics of the neighborhood. But if you look at the history in Portland, when Portland decided to upgrade the Northeast, that caused prices to go up, so the Black community there got displaced. This is a well-known fact and Portland was smart enough to be able to realize that was a mistake and they needed to take into account displacement.

Alright. So when you are deregulating zoning, the problem is that you increase the land value. The ones that benefit from that are investors, not community members. The value of the properties around them go up.

But if you’re a renter, what happens is your landlord says, ‘My property value has gone up. And there’s a willing buyer who’s one of these investors. So I’ve either got to get your rent up or I’ve got to sell it for this higher price.’ And boom, there you go: displacement.

In a different era, we knew that as gentrification. What’s going on now and is well documented is large equity firms are buying up these kind of places.

Let’s talk about what happened to the Westside. There were two buildouts in this neighborhood. One was pre-war, late ‘20. Our house was in ‘29, you know, as the farm went away and it got divided and things like that—what people would call sprawl actually back then, but now they think of it as being inner-city.

So that was one buildout. Then there was the war and immediate post-war, houses were built a little less. They were smaller. They weren’t quite as nice quality, pretty modest and so on.

But then what happened is really telling. This area was zoned two-family zoning. But two-family zoning at that time wasn’t limited to two families or to two houses. You could have a single-family house, you could have a duplex, you could have a house and an ADU, there were also apartments.

So if you look in closer to town from about, oh, Madison into town, you’ll see these classic four-over-four, or six-over-six apartment buildings, typically sited either on a corner or a double lot. That’s middle housing. And we’ve had it for decades, and so that was the way the neighborhood was when it was a healthy, thriving neighborhood.

Why was it different when I got there? Well, it was different because many of the households that lived through that period left, they died off, or they went to a care home or whatever. And new families moved by choice, not being forced by any means, but moved by choice to more modern outer neighborhoods with more modern houses, more modern fixtures, you know, and the difference between the way things are structured in a house with number of bedrooms and so on.

So by choice, not immediately post-war, but like ’50s and so on, what we think of as sort of suburban development arose in Eugene and people did not move back in to replace the elderly households that were dying out or moving up.

What happened then was properties were sold off at discount low prices now ’cause there wasn’t demand there. And so the bottom feeders moved in. And they bought these houses and first off, they turned them into just cheap unmaintained rentals. And they ended up putting in two units, three units, didn’t maintain them, they got worse and low-rent stuff.

But they also then jammed in duplexes, triplexes, and even in some cases, fourplexes in the backyards looming over the adjacent yards. That meant those were unattractive for economically mobile people.

So this neighborhood became what a good friend of mine is referred to as a place ‘where people had to live, not where they chose to live.’ That’s why I bought here, because I didn’t have the money. I really hadn’t realized how bad our neighborhood was when I first bought, I’ve got to say.

And what exacerbated it was the zoning change. So instead of the original two-family zoning, which did allow duplexes and apartments as well as ADUs and everything, they changed it to medium density housing. This was an earlier movement by the planners to prevent sprawl.

Instead of growing up and not out, it grew with covering open space, cutting down trees, etc. etc. Alright, so that is what led to a neighborhood into which I moved in which—it was rough.

And because people were forced to live here and the conditions weren’t good for them, people didn’t care for the neighborhood. So if there was a drug dealer on the corner, you know, you were around there, you just lived with it, and you hoped to get out someday. Alright?

So that’s what happens and this comment that neighborhoods are an outdated concept and that neighborhoods evolve—neighborhoods can devolve as well. And that’s what the threat of all this middle housing BS is, is that they are driving people out.

And the other piece of it is, this doesn’t do any good. This does not lower housing costs. Housing is not like soybeans where you just add supply and prices go down. There is a well-understood housing economics (well-understood outside of our Planning Division and City Council) that housing economics have what’s called very low intercategory elasticity. So they don’t work by supply and demand outside those categories.

And the most important category, the way that things are categorized, is location. That’s what segments the market for housing mostly. There is not cross-system elasticity because of that.

So there is also a categorization just of price and style, you know, condominiums and so on, when you’re building what are either sold at (or rented, according to this price), if it were sold, $500,000 houses, $500,000 to $700,000. That’s what’s being built in these so-called ‘middle housing’ things. You are not doing anything that works through supply and demand.

Ask the city what net gain has there been in housing, at different affordability levels, and where and how. Net.

A huge number of apartments have been built out near where Hyundai was (involved with Hynix), in West Eugene. That’s a good way to build housing. Huge numbers. It’s probably not ‘affordable’ or whatever, but it’s going to add supply that’s probably somewhere in the middle, right?

So all you have to do is say: Show me the numbers. The numbers are going to be commensurately small, you know, with the fact that they’re also not doing as much damage. Whole communities aren’t being displaced, right? Individual families are being displaced.

So that’s the other piece is, it’s just ignorant of housing economics, and that’s where I would recommend that the planners put down The Color Of Law book and pick up what Jane Jacobs has written.

Cities are made from great neighborhoods. Diversity is having places that people want to live and that don’t exclude anybody who wants to live there.

But it does constrain what they can do. So if you want to live in the brewery district, you can live in a six-story building that shares a wall with the next six-story building, and so on. Nothing wrong with that at all. You can live there.

But there should be opportunities that respect different kinds of character. And yes, there are going to be price differentials and the solution to that is that we need to have opportunities within neighborhoods that are not just cramming people into warehouses, but which have tree-lined streets and open spaces stuff.

And you do that by subsidized housing. You introduce the opportunity for people who don’t have as much economic mobility to live in places where people who do choose to live. And for decades I have been a supporter of subsidized housing, including transitional housing, like Sponsors and so on, they are always the best form of housing to get in your neighborhood.

So there are two housing crises. One is households that are truly housing cost-burdened, and there’s a very simple, intuitive definition of that: After you pay all your costs for housing, including utilities, whether it’s rent or mortgage or whatever, you don’t have enough left for basic human needs. Health care, transportation, education, and so on. In some cases, food. So that’s the real, most severe crisis.

Alright, so then the other crisis is housing ownership. Ownership—whether it’s the classic mortgage or whether it’s cohousing or something like that, but owning housing of some sort, condo, whatever—that is one of the great wealth builders in America. If housing weren’t such a good investment, you wouldn’t see all the private equity firms gobbling up all the housing they can.

Alright. Owning some of a housing asset that you live in. It’s becoming very, very difficult, especially for younger. Households or individuals to participate in that. So those are the two crises.

What isn’t a crisis is housing choice. I couldn’t buy the place I wanted to. In my young 30s I had a job as a faculty member at the U of O and I had to buy a slum house because I couldn’t afford it yet, right? It is not a crisis if somebody can’t buy the house they want for their income.

The house you should have the ability to participate in, ‘if you work hard and play by the rules,’ as Clinton said, is one that’s safe, comfortable, and you have a quality of life.

It doesn’t mean you have a game room and five bedrooms and whatever.

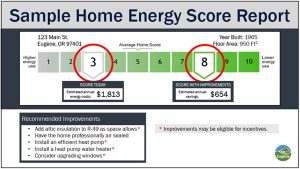

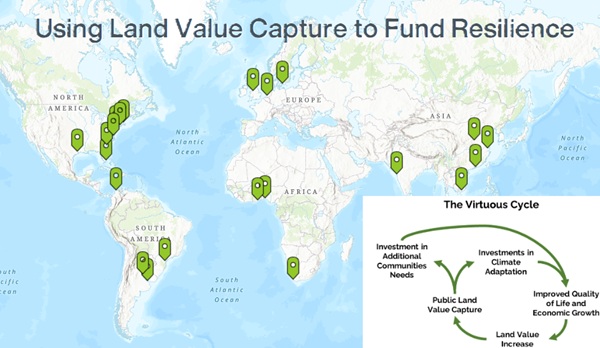

So let’s look at the two crises. So the one crises of affordable housing / cost-burdened households has to be addressed with subsidized housing. There’s a very straightforward-in-practice (not in Eugene, but elsewhere) way to approach that: Land Value Recovery. This is what they’re doing in Boston.

When Eugene deregulated residential zoning on most of the land that’s in residential zoning in an extreme way, they didn’t change the zone designations. But they did radically upzone from—to allow increased density by up to five times. I don’t know that anybody’s actually ever calculated this, but that generated or created millions, probably hundreds of millions of dollars in increased land value.

Alright, who created that value? Our community did. Who is benefiting from that value? None of the community. Just the investors.

So it’s very simple. Let them make a profit, but let some of the value that the community has created comes back to the community, and that’s what you use to pay for subsidized housing. You can go to other cities in the United States, you can go around the world and you can see where they’re doing it.

The crisis of home ownership, that has to be done at a higher level, generally in terms of simply financing. It worked with veterans financing after the war, to get into housing. Basically, it needs to happen at a national level.

We do have some housing programs that help somewhat—FHA and so on—but we don’t have it at the level that we should, which says, again, I really like this phrase, which is: ‘You work hard, you play by the rules, but you get a chance at the American dream,’ you know, part of which is typically owning a house.

So that solution is not one that can be handled in Eugene. It’s also not the same level of crisis as housing costs burden where you might end up in your car the next week. Right?

But one thing we don’t have is a crisis that says we need to build more $500,000 condos because that’s going to bring the price down of those condos and that’s what I want to buy. That is not a crisis, you know? That’s the market working, okay?

So I don’t have anything against that, letting those build, but don’t let them build so that they then ruin the quality of life of somebody next to it. And don’t ignore neighborhood character when you’re setting the rules for that. We don’t have to do something that’s regressive or reactionary. That’s what we’re doing with this, ‘Neighborhoods don’t matter.’ Those are all reactionary things.

We can take a truly progressive evidence-based approach to it because Eugene isn’t leading in this. So planners, put down The Color of Law, put down your 3PM virtue signaling, and pick up what happened with Moses, what happened with Eugene when they did the downtown mall, what happened with Westside when they upzoned it without keeping standards in place.

And pick up Jane Jacobs and Jane Goodman (who’s another great author), and get out in the communities and understand that we do have community character and it is inclusive. And that’s the story.

Presenter: That’s Paul Conte, who suggested in 2025 that instead of following Robert Moses in destroying neighborhoods, that Eugene instead look to Jane Jacobs and Jane Goodman, and consider land value recovery to build subsidized housing.