Youth Radio interviews activist Eloise Navarro

13 min read

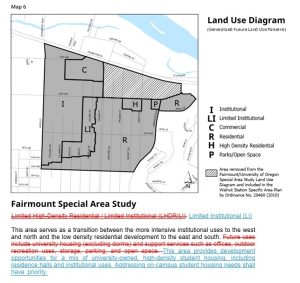

The city cut her off, but she has a lot more to say. Offering comment at the council meeting Oct. 24, Eloise Navarro.

[00:00:08] City of Eugene: Next we will hear from Eloise Navarro.

[00:00:11] Eloise Navarro: Hi everyone. Thank you so much for this opportunity to provide testimony. My name is Eloise Navarro. I am a student at the University of Oregon. I also reside in Ward 2.

[00:00:21] Besides being a student, I’m a co-director of the Climate Justice League. I’m an environmental justice fellow at the University of Oregon. I’m the National Fossil Fuel organizer at 350 PDX. I’ve received national scholarships for environmental work. I’ve completed fellowships in campus divestment from fossil fuels. I’ve spoken at conferences with peers about student organizing and I’m here, and all of that just to say, that I’m really tired of showing up at city council meetings and asking for some basic climate justice requests.

[00:00:55] So I’m here in support of building electrification.

[00:00:58] And so all of that to say: I just turned 21 and I have shaped my whole life around pursuing climate justice, especially for our most vulnerable populations.

[00:01:10] And this isn’t my first time testifying, I started when I was a sophomore. I’m about to graduate with my bachelor’s degree. And I’d love to say that all of this is out of love and joy for the environment, which part of it is, but it’s also out of obligation. I love being passionate about climate justice and it feels like it’s my calling, but to have your passion be rooted in the changing of systems and of structures, it’s really overwhelming, especially when you’re young.

[00:01:35] And I’m sure as city councilors and as the mayor and as city manager, you might resonate with that feeling of overwhelmingness and wanting to change things for the better. And I get that, because there have been many folks on council who have really tried to make some positive changes. And so the reason I share all of this is because I know it’s possible, as when I’m studying at the university, I’ve seen smaller communities with much less resources be able to make even bigger impacts for the climate and for the health of their communities.

[00:02:09] I’m living in a home that is poisoning me. I’m a renter. You all, unless you have all electric appliances, are living in homes that are poisoning you and poisoning your children and your grandchildren.

[00:02:21] I work with BIPOC high schoolers who are being poisoned at their schools and in their homes and at the places where I teach them—

[00:02:29] City of Eugene: Thank you, Eloise. Your time has concluded.

[00:02:31] John Q: From the Youth Radio Project, Jenah and Journey followed up with Eloise Navarro.

[00:02:36] Eloise Navarro: Hey there, my name is Eloise. I am actually a student organizer at the University of Oregon and for the past three years or so have been working on different campaigns on campus, mostly related to fossil fuel resistance.

[00:02:53] So it started with divestment. So that means that at one point in time, the university had investments in fossil fuels, and we did a lot of research to find out what that really looked like. Eventually we found out that they didn’t have investments anymore. So we’ve now shifted to looking at fossil fuel infrastructure.

[00:03:13] So lots of my background is in fossil fuel resistance. But even before that I had participated in more forest defense-related work, so that was going out into the forests surrounding Eugene and looking at places that were potentially going to be sold to be clearcut or logged. A major—the reason why that’s important is because lots of these forests were old-growth forests.

[00:03:37] Old-growth forests are forests that are significantly older, have much more bio- and ecodiversity, are sequestering a lot more carbon. And so they’re really, really important for keeping carbon out of here. And so that’s how I kind of started getting involved in forest work specifically.

[00:03:56] John Q: Eloise said she helped organize the Deep Roots camp this summer.

[00:04:00] Eloise Navarro: The Deep Roots camp was actually originally planned with 350 Seattle. But then they couldn’t host it, so it eventually made its way down, 350 Portland was maybe going to do it, and it made its way to 350 Eugene.

[00:04:13] And so the camp was actually a collaboration between myself just as an organizer (and I also do some work with 350 Eugene), but mostly just as myself and a bit of a background in climate and forest organizing. And then we also had folks from Cascadia Wildlands, which is another organization in Eugene working on various aspects of forest protection, and then the Pacific Northwest Forest Climate Alliance and then Portland Rising Tide. So different climate groups that approach climate action in different ways.

[00:04:44] So the idea behind this camp was to connect these two really important things, forest defense and climate action. And so if you’ve heard of the environmental movement, it’s got fossil fuels, it’s got pipelines, it’s got forest defense, lots— it’s a big thing.

[00:05:01] And the forest and the climate movements have been a little bit separated, even though they’re definitely, really, really inherently linked together because environment and climate, it all affects each other. So the goal of this camp was really to bring those two movements together and to really allow a space for folks of all backgrounds, whether you’re completely new to forest defense or climate work, or whether you’ve been doing tree sits for 10 years, like, this is a space for you to come and build community and learn from each other.

[00:05:35] And so we structured it. It took place over a weekend. It was two nights of camping. So this camp was about as lux as it could be. I wouldn’t call it glamping, but we had some really well-organized folks helping out with some of those things. And so we had a whole kitchen crew that did meals for breakfast and dinner and then would put food out for lunch. But this was a group, I think a core group of four folks who had various experience in cooking and doing this kind of work too. So they’d provide like really awesome and like accessible meals for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

[00:06:15] And that was also, still, even that process of the kitchen was also collaborative. They had volunteers helping out at every meal, whether it was with dishes or with serving. But we had really awesome food. You know, in the morning we’d have like eggs and veggies and grits. And for the dinners we had really amazing like veggie curry and like all these like pretty elaborate meals that you wouldn’t expect to have in a forest camp. So we were very, very well-fed.

[00:06:44] And we had various workshops, trainings, and a panel as well. And so it was both about what some people might call like hard skills. So we had folks learn how to paint banners effectively and learn some tactics for hanging banners and doing movement art.

[00:07:05] And then it was also some more theoretical and community-building conversations around what has forest defense and climate work looked like in the past? How has it been harmful? How can we make it more inclusive and be in more community with each other? So we are approaching two movements a few different ways. So with these hard skills, but then also with these kind of conversations and community-building things.

[00:07:30] So some things that took place: We did a field checking workshop, so that means that folks went out into the forest and learned to how to monitor timber sales. So it was about how to look at different plots of land.

[00:07:43] John Q: They looked at how groups in the past had not listened to indigenous voices.

[00:07:49] Eloise Navarro: And then we also had some indigenous organizers come down from BC (British Columbia) up in Canada and they kind of talked about decolonization and climate work, because one of the ways that it’s been harmful in the past is that folks haven’t really listened to indigenous voices about the forest. And that’s especially important and kind of the foundation for having a healthy, successful climate movement. And so we included that.

[00:08:20] If folks have heard of the Fairy Creek blockade, the BC folks had participated or been involved in that movement. Their homelands is the Fairy Creek spot up there in BC and so first, they’re sharing a lot about their own stories, but a lot of it was really about how activists and organizers can do better, particularly white or non-indigenous organizers because for a very long time especially in climate and forest movements, indigenous voices have been ignored. There have been folks making decisions for, or on behalf of, indigenous people, on indigenous people’s lands, a lack of connection with the earth.

[00:09:01] And I think we’ve seen that a lot of times in that lack of connection, that lack of listening to indigenous folks, and how they feel that the land needs to be treated and how we need to be in community with one another has led to some really unhealthy habits in activism spaces.

[00:09:21] …One example is the climate doom and the really strong pessimism and ‘There’s no way that we’re going to get out of this and there’s nothing that we can do about it.’ That’s one of the most harmful narratives that exists. And so, one point of them being there was to say. ‘Listen, like, there’s no time for climate doom, and let’s actually take a chance to build community with one another, with a specific focus on, let’s build community with indigenous people because they’ve been ignored and mistreated in this particular movement for far too long.’

[00:09:58] And so that’s one thing they shared about. And one of the things that I really took away was that ‘cause in my organizing it’s hard to connect with indigenous communities and for good reason, is that lots of folks will waste indigenous folks’ time. And lots of people just want their stamp of approval to feel better about themselves and the decisions that they choose to make. And one thing that has stuck with me was, they said it could take 10 years, it could take a decade to create a solid, reciprocal, meaningful relationship with an indigenous person or an indigenous community.

[00:10:37] And I think for some that might seem really overwhelming. It’s like, ‘Whoa, what you’re telling me, I have to put in like years of work to make this happen?’ But it’s so worth it, especially in this space. And what I heard from that wasn’t, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s not worth it, that takes too long.’

[00:10:53] I think what a lot of people heard was, ‘All right, if that hasn’t happened yet, then today’s day one of that decade, and that’s okay.’

[00:11:00] And so I think that was one of the main takeaways as well as, you know, they were extremely vulnerable in their experiences in activism and climate and shared some specific ways that like they had personally been wronged or harmed by the movement.

[00:11:16] And I think for lots of people, that was helpful to hear. Okay, these are maybe things—maybe I have or haven’t done these things in the past—but it’s good to know that this type of action is not okay. Or that I need to be more aware when I do this thing in my organizing or I need to consider these voices. So there’s also that element of it.

[00:11:35] But I think overall, it was extremely powerful and I think a lot of people walked away knowing—finally, maybe—the importance of indigenous people being involved. Not just involved in the activism, but really centering those communities and finding different ways and finding many ways to uplift and support them.

[00:11:58] John Q: Eloise said one big goal was to continue working together after breaking camp.

[00:12:03] Eloise Navarro: One of the most important things that we kind of had conversations about was affinity groups. And so that was another main goal of the camp, was for folks to get together based off of their interests and what they were wanting to do with the new skills that they learned and actually do something afterwards.

[00:12:17] And so folks formed different groups where they had shared interests. And so, for example, I’m participating in an art affinity group, and so, now that the camp is over, we’re still in touch talking about: What’s some ways that we can make a difference in the climate movement using art?

[00:12:35] At the camp, we had a really, really diverse group of artists. And so myself, I’m mostly just interested in art. I do a lot of collages. I have experience painting banners and signs, so it’s lettering, all of that. Other folks had really, really vast experiences ranging from casual graffiti art to incorporating music in climate action and how to use audio and how that’s a really powerful tool that hasn’t really been tapped into as part of the climate action.

[00:13:09] And then some really great conversations came out around that about recording music and having a speaker play really powerful music and powerful messages from a different piece of art. And so it ranges from as classic as, like, banner drops and signs at marches to really, really like unique takes on how to involve people and get people thinking.

[00:13:33] One that lots of folks had experience with (or happened to have experience in this group) is zines. Zines are like smaller collaborative magazines really meant to, they can have lots of purposes, but really meant to educate folks. And so we had thrown around, maybe let’s put together a collaborative little zine with little writing or poems or song lyrics about the forest or whatever the issue might be or the topic might be. It was a really, really cool range of folks and even, I’d say that art was even central to the camp itself.

[00:14:08] One, because somebody hosted a movement art workshop, but then it was also part of having fun together. And one night we even had a ‘No Talent Show’ where folks came and if they could play music or sing, they could do it and lots of folks sang really awesome songs related to the forest and to organizing, some not related, and it was just fun and that’s cool too.

[00:14:33] But it was really cool to get experience both in, yes, we’re planning, we’re doing something, but also it was, we found it during the camp as a way to have fun together. And so yeah, art has played like a really, a really big role throughout the entirety of the camp. And also I’m sure in our affinity group moving forward.

[00:14:52] John Q: Eloise said the camp was well attended from throughout the northwest.

[00:14:56] Eloise Navarro: We had folks from all over attending, so from Eugene, from Portland. We even had folks from other spots in Oregon as well as from Washington come all the way down. And so it was really widespread and we had probably around 75 folks come out to the camp and participate.

[00:15:15] I was going to say it’s really, really mixed in, in the ages. So we had a couple folks accompanying that were young, like elementary school age, all the way up to older folks. And so it was really awesome to see that kind of multi-generational collaboration at the camp. And I’d say that was also one of the great benefits that came out of it.

[00:15:36] So we tried to bring in a lot of new voices, so it wasn’t just us teaching, it was folks who had a bunch of different experiences in the movement.

[00:15:44] One group that is also still in touch is a Eugene-based group, folks coming together to oppose the Flat Country timber sale. I know there’s a group based in Eugene that’s working on like indigenous solidarity and getting plugged into local indigenous struggles.

[00:16:00] And so yeah, I think a lot of groups are actually just now at the point where they’re reconnecting now and seeing how to move forward. And so it’s really, really exciting to see and I think that we are going to see some continuity and really great work produced after the camp as well.

[00:16:16] The pandemic especially has really harmed our abilities to connect with one another and both in very simple ways, in like, you know, through friendships and interacting with other people, like literally just interacting and talking with other people. Two bigger things is getting a bunch of people together to try and go to a protest, for example, or get out to a march or get out to a camp. And so I think if over time we see more community resiliency, and I think that is something like in five, 10, however many years—you’ll know a difference. You’ll know there’s a difference because I think you can feel a difference. Because I think right now we feel the weight that the pandemic and that burnout has had on us because everyone can feel that individually, and I think it’ll be the same when we’re finally able to be reciprocal and be in community with one another.

[00:17:08] I think we’ll feel it on our insides or in our insides. So that’s one thing that’s a little less measurable. But I do think resiliency is going to be a huge part of it. And yeah, are people having the same conversations and are people interested in the same concepts? Are we moving forward together as a community?

[00:17:29] And also at the very foundation, Who is your community? Is Eugene your community? Is your small group of friends your community? Figuring that out too, and just finding that sense of a group is also going to be another thing. And so those are bigger concepts that I’d love to see happen regardless, in any space.

[00:17:47] But I think especially since Deep Roots had such a strong emphasis on getting to know each other, from the most basic to the most complex levels, I think that’s going to be really important. And I have a feeling that we’re moving in the right direction and I’m pretty hopeful.

[00:18:07] John Q: Eloise Navarro meets with the Youth Radio Project.

[00:18:10] Journey: Hello, I’m Journey, today I’m here with Jenna on Youth Radio at KEPW 97.3 FM streaming online at KEPW.org.