‘Greenfire Revolution’ can help us survive the era of climate change

5 min read

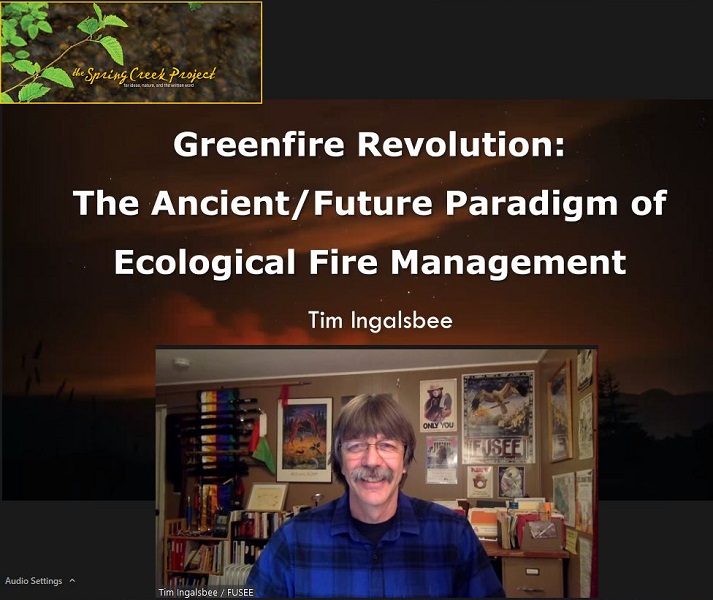

Tim Ingalsbee offered the Greenfire Revolution as an alternative to the military-industrial-fire complex.

Speaking this week as part of OSU’s Spring Creek Project, Executive Director of FUSEE (Firefighters United For Science Ethics and Ecology), Tim Ingalsbee.

[00:00:10] Tim Ingalsbee: I love fighting fires. I love the adventure, hiking and camping and wild places, dancing with wildfires. I love the hard physical labor of it— getting sweaty and sooty and not caring. I love the crew camaraderie. I was raised in athletics and team sports. And yeah, you might say firefighting was kind of an extreme sport to me at times. So I was able to pay my way through college. It was a great life: Living in the forest fighting fires in summer, living in Eugene learning about fire ecology and fire policy in winter.

[00:00:47] And over time I started developing some cognitive dissonance. The things I was learning about fire ecology, fire policy, fire, and culture in school were contradicted by what I was doing in fire management in summers. And this gap between fire ecology, fire science, and fire management, it continues to grow, almost heading in opposite directions every year. What we know and what we feel we should do is often the opposite of what we are doing in fire management.

[00:01:25] The Greenfire Revolution, to me, that’s a symbol for this paradigm shift in fire science to management. And it’s a revolutionary shift in thinking about wildland fire and humanity’s relationship with it, shifting from fire exclusion to something like fire inclusion.

[00:01:47] This emerging paradigm, yet to be named, could it be a paradigm of fire resilience, fire regeneration, ecological fire management. Like all revolutions, this Greenfire Revolution is not without struggle. And the current dominant fire exclusion paradigm is maintained by systems and structures that are vested stakes in maintaining the status quo. We have government agencies that gain immense power. They can do things on the land unencumbered by environmental laws or regulations or those pesky environmentalists. We have private companies that gain immense profits from engaging in this kind of perpetual annual war on wildfire. And so there’s a vested political and economic interest in maintaining the existing dominant fire exclusion paradigm. You might call this the Fire Industrial Complex.

[00:02:41] But it’s clear that it is failing to guide us to understand or adapt to our changing reality of megafires in the era of climate change— the Pyrocene, as Dr. (Stephen) Pyne calls it. The future appears to be more of an indigenous model of community fire stewardship, replacing this imperial model of state-dominated fire suppression.

[00:03:09] How did I come to this paradigm shift? Got a smoke report. It’s in some very rugged remote area of the dense forest. I spent a couple hours sniffing it out on a search and destroy mission. And when I came upon the little lightning fire, I dutifully spent hours lining it out, mopping it out, making sure every little smoldering ember put out, saving this one smoldering stump for last. And inside its hollow was this tiny flame, the last flame of that fire area. I smothered and I chopped and I put out that flame, but when it was over, I felt a real sadness, a real loss, that that fire belonged there in a ways that I didn’t, at least in what I was doing, didn’t belong there.

[00:03:57] Instead of stopping those fires, we should it be steering them. Steering them away from homes, communities. So let’s change the name of this occupation, change the identity of the people doing fire management to something that is more evocative of ecological fire management. Instead of ‘Firefighters,’ call them ‘Fire Lighters,’ because that’s really what needs to be done—starting prescribed fires, starting cultural burns. ‘Fire Guiders,’ to help guide the fire into the places we want to burn, away from those places we don’t want to burn.

[00:04:33] So how’s this: ‘Fire Rangers.’ And their mission is to start fires, steer fires, steward the land with fire, keep communities safe using our best science and the best of our native legacy lessons that they are offering to share, to actively manage wildland fires with ecological goals and objectives in ways that maximize their social and ecological benefits, but minimize the damage and costs that come from fire management actions, mitigate their risks and hazards to people and property. And it’s a very holistic approach to actively managing wildland fires. Ecological fire management includes human communities in our notion of ecosystems where people are really a part of nature, and not assuming that stand apart from nature.

[00:05:39] I believe we all have some kind of inner, innate love and attraction for fire that’s part of our species evolution. I call this pyrophilia, love of fire. And I really draw on the works of Stephen Pyne, talking about the human fire legacy, our unique human relationship with fire, the only species on earth with the knowledge and skill and ability to start a fire. And the only one crazy enough to try to stop them too.

[00:06:10] As a species, we have relatively big brains, small jaws, and hairless limbs, because our physiology evolved as attending fire. We brought fire into our homes. We worked with fire on the land. We’ve developed this innate love and attraction for fire that developed over a million years of hominid evolution, multiple millennia of living and working with fire. The creation of human communities and cultures and language, maybe even religion and the tools and technology, Homo sapiens wouldn’t be human beings without this vital relationship with fire. And it was a reciprocal relationship: We fed and sheltered and nurtured fire, and in turn fire sheltered and fed nurtured people.

[00:07:04] I did a study on fire religion. Absolutely ubiquitous: Every religion, ancient, contemporary, great, small, there was a literal or symbolic role of fire. And I dare say there’s probably not a single church or synagogue or mosque or temple that doesn’t have fire somewhere in it. It’s a living legacy of what was once the dominant belief of our loving relationship and vital reciprocity with fire.

[00:07:36] And this is deep-rooted. And this is what gives me hope that we can shift our own paradigm and relearn and renew our relationship with wildland fire. And my hope is that both fusing what we’re discovering and learning in fire science, with the cultural burning practices and traditions and ancient wisdom of indigenous communities— that shows us the path forward. Looking out over the horizon, into the future, drawing from the past, how we might be able to work and live with fire on the land. And so that’s really offers my hope for humanity.

[00:08:19] John Q: Tim Ingalsbee of FUSEE, speaking at OSU’s Spring Creek Project. Stephen Pyne will be speaking Feb. 22.