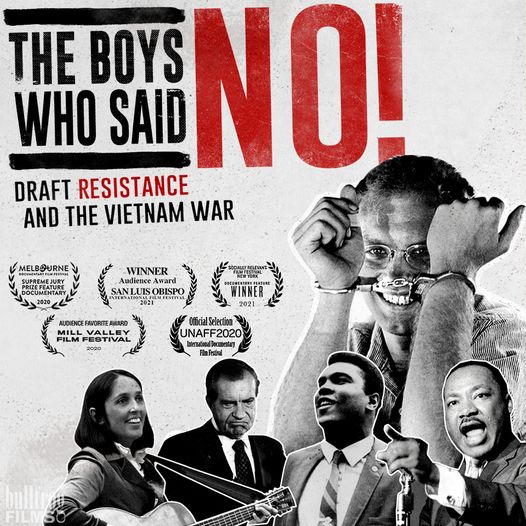

Judith Ehrlich film adopted as blueprint for nonviolent resistance

10 min read

At a Eugene screening of the documentary The Boys Who Said No, about conscientious objectors during the Vietnam era, comments and questions for the film’s director, Judith Ehrlich. She was introduced by her sister, Anne.

[00:00:12] Anne Ehrlich O’Brien: I’m Anne Ehrlich O’Brien and I have the pleasure of introducing my baby sister, Judith Ehrlich, who is in Brisbane, Australia.

[00:00:23] Judith Ehrlich (director, The Boys Who Said No): Thanks, Anne. Lovely to be there with you and the Eugenites. It’s raining here. I thought that was appropriate. It suddenly started raining five minutes ago before I came to visit you in Eugene.

[00:00:34] I just finished an animated podcast I did with Daniel Ellsberg and it’s on a website called DefuseNuclearWar.org, part of RootsAction.org. There’s a couple of these three-minute pieces that are up there now, if you want to look at them, around reducing the risk of nuclear war, with Dan (Ellsberg), who’s an expert on that, as well as a whistleblower against the Vietnam War.

[00:00:58] I’m very pleased you have a great house there for the film and I’m just here to take questions and answer any questions for you. I did get one question, which is often asked, which is: Where does this leave us now that we don’t have a draft? And how do young people relate to war and to serving in the military?

[00:01:17] And Bob Zaugh, who’s one of the characters in the film, he’s been just out there just constantly taking this film to college groups and all over the Los Angeles area. He goes a couple times a week and takes the film out to groups and he says the average class, like a regular class with 30 people, one might know what the Vietnam War is, often, sometimes two, but that’s it.

[00:01:41] I mean, not only do they not know enough about military service and the draft or the draft resistance, they don’t know that there was a war. And he keeps telling me, this is a story people do not get in the more recent generations. He’s speaking about the not high school, but college students.

[00:01:58] Jack Radey: My name is Jack Radey. I have a problem with the film to some extent. And my problem is this: It very much emphasizes those who took a principled nonviolent position and voluntarily went to prison to protest the war, and bless ’em. They were always there and they were always important.

[00:02:21] They were only a very small part of the anti-war movement, and the movie badly mischaracterized Stop the Draft Week in Oakland, and didn’t even mention the one in New York, where I was.

[00:02:36] It was not the Weather Underground. They did not go out to make war on the police or Oakland. They went out to nonviolently demonstrate in the streets against the draft and to stop the buses from getting to the induction center. It was the police who brought the violence and made it a violent demonstration. Thank you.

[00:03:02] Judith Ehrlich: Thank you. I’ve done some pretty extensive research on that week, reading every newspaper that was published at the time and talking to many, many people who were there, and I can understand why you might say that.

[00:03:17] It was definitely the intention of the organization to stop the draft nonviolently. And as Joan Baez says, when she gets off the bus, that was the case on day one. And then the few days in between were not as big of crowds, but towards the end of the week, a lot of people took advantage of the activity to come in with a more aggressive approach to the police and of course the police did aggravate it. And as you could see from the footage, the police were out there en masse the whole week.

[00:03:49] But the intent—I think we do represent that correctly—the intent was very much to do nonviolent resistance to the draft, but it did disintegrate into a very violent, and that’s what David (Harris) talks about, when he said it was an opportunity we missed by the people who came and created a violent situation with the police.

[00:04:09] This is my fifth film on this general subject, conscientious objectors. I’ve done a radio series on the international conscientious objectors. I’ve covered big groups of conscientious objectors. This was a very targeted film. It was about a specific small group. And it wasn’t ever intended to tell the story of the anti-war movement. It was intended to tell the story of a group that’s been completely forgotten historically. And that was our goal, and that’s what we focused on.

[00:04:37] Steve Dear: Hi. Thank you for your beautiful film. My name is Steve Dear. I want to thank everybody in this room who raised their hand and was doing something to resist this war in the ’60s, ‘cause I know the loss that is forever, and I know the loss of one American soldier, one of those 58,000 soldiers.

[00:04:55] Anyway, yesterday there were 10 people standing outside protesting our country’s involvement in Ukraine. It’s been going on every week for the last 10 weeks or so, and that was the most people we’ve ever had, 10 people. It’s a group called Planet vs. Pentagon here in Eugene, and we invite you to join us and get involved. There’s signup sheets. Michael Carrigan and Sue Barnhart are down there in the corner. I’m here.

[00:05:22] Anyway, thank you for your beautiful film and I hope a lot of people see it. I’m sorry, I don’t really have a question. Your work, the work that’s reflected in the film has to be happening today, and I hope you agree with that. Thank you so much. (Absolutely.)

[00:05:39] Todd Boyle: So what we did during that era was we stood up and we protested and we refused to get inducted or we refused to go along with the military orders. We wanted the brig and so forth. And there’s 25 or 30 people right in this audience, in this small audience, with the gray hairs, who actually did this. I just happened to be, I’m not a good man, but in 1971, I had found myself in the Navy, and because of the heroic actions of people like Jack Radey and the people who came in the earlier years, in ’68-‘69, it was relatively easy for us to organize our units in the Navy and get general discharges and then go on and go to college on the GI Bill.

[00:06:16] And I helped to organize several dozens of people in my small way and get out of there in my usual selfish manner. But I actually appreciate the efforts and the sacrifices that were made by people who came before me in ’68, ’69, ’70 when actually aircraft carriers refused to sail. I mean, people made huge sacrifices before I came along. (Yep.)

[00:06:37] John Q: A protester at the University of Wisconsin.

[00:06:40] University of Wisconsin protester: I have the same criticism of this film that you were given at the beginning. It does focus on a small group and when seen by naive observers it might be assumed that group is larger than it was.

[00:06:58] In fact, what we found (and I was at the University of Wisconsin) what we found was that every time we demonstrated against the war, we were attacked by the police. I still take painkillers every day, twice a day for what they did to my hands, which was make them into pulp.

[00:07:16] We finally decided that nonviolence, it was sort of like SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee)—you got tired of being beaten, you got tired of it. So every time they tried to, we would just turn away and go down State Street and break every window and bust up and burn things and raise hell and make the war so expensive that they might actually think they would quit.

[00:07:45] I think it’s very important that you show these kinds of things. But it’s the environment that’s the issue today. And that’s what young people are mobilized around.

[00:07:57] John Q: At the Encircle Films discussion of her documentary, The Boys Who Said No, director Judith Ehrlich.

[00:08:03] Judith Ehrlich: Well, in response to that, the groups that have used our film the most are—

[00:08:10] DJ Suss D: Extinction Rebellion.

[00:08:11] Judith Ehrlich Yes. And they’re in Australia too and in the U.S. They’re international, but they have used more copies of this film to organize than any other group.

[00:08:19] So they see that we’re not saying, ‘Do this about the Vietnam War now.’ We’re saying, ‘Here’s how resistance works.’ And we have had a lot of comments from young people, and a lot of reviews saying this is the blueprint for resistance.

[00:08:32] And it isn’t only about the people, it focuses on these groups who use nonviolence, who even though they got bored with it and it was really hard, and it’s always really hard, they kept at it. And I think they’re a model for people who don’t want to resort to violence, even though that’s an easier route.

[00:08:50] And I can say I hit a cop over the head with an umbrella…and I wouldn’t do it now. I think I’ve been inspired by these people that there are other ways to do it, and if you can really stick with it, it’s an actual path to success, which violence never is, in my opinion. And I hope that came across in the film.

[00:09:12] Coast Guard veteran: I was at Asilomar in 1962, which Joan Baez talked about there in the film. And along about 1963, I managed to get myself flunked out of college and I went to try to get a CO (conscientious objector) and at that time, one had to profess a belief in a supreme being, which I could not do. I still can’t, and I was offered the opportunity to join in with a group in San Francisco, and I had no faith in the court system of the United States, so I did what a lot of other people did. I joined the Coast Guard.

[00:09:55] I thought I was going to stay home, did not, except for eight months in San Francisco at the very end. The rest of the time it was basically overseas. And I just commend you for this film. It’s only films like this that will keep what happened and what was necessary alive. And I just thank you for this film.

[00:10:18] Frank Harper: Hello, my name is Frank Harper and I’m one of those who ended up in Vietnam. My father was a World War II veteran. He was wounded three times. He was with the 133rd and he ran mule trains up in the Apennines. He ran supplies and ammunition up to the front and he hauled casualties back on the mules.

[00:10:38] So, you know, I couldn’t resist. I couldn’t, I would never be able to face him because he was a staunch Republican and said, ‘No, you are not. You’re going to serve this country.’ He never mentioned anything about what happens if you were in Europe or North Africa and you resisted fighting. You either got hung or you’re in front of a firing squad.

[00:11:02] Pvt. Eddie Slovik was one of ’em. Louis Till, Emmett Till’s father, was hung for supposedly raping. And there were 96 Americans that were either hung or put in front of the firing squad. And that is something where you mentioned there’s only two students in the class—this needs to be taught. That if we don’t, we’re going to lose all that. It’s going to repeat itself. And boy, I don’t want anybody to end up in another Vietnam-type war.

[00:11:30] Alan Rosenfeld: My name is Alan Rosenfeld and it was a beautiful film but what gets forgotten is how much the resistance to the draft wasn’t opposition to the war. It was because so many young people were being forced to go and give up their bodies and their lives, that they ended up resisting the war. Ending the draft, that was a strategy of the Nixon administration. They ended the draft in order to slow down the resistance of the war.

[00:12:03] What we have now is, they need less soldiers because of such a high-tech military now. Doesn’t mean they’re killing less people. Right. They have drones, but the reason we don’t have a, we don’t need a draft right now is also because we have such extreme poverty and we have so much manipulation in the poorer high schools is where, whether it’s poor whites or poor blacks who are not just being manipulated, but also realistically are given no choice.

[00:12:34] Lots of people I know I talk to are making that choice. If they manage to survive a tour in Afghanistan or Iraq they’ll then come home and have a GI Bill and have an education. And otherwise they’re going to be working in a Safeway or a drug store.

[00:12:48] And it’s a beautiful film, acknowledging them, and I’m grateful for that. But we have to remember that it was self-interest that led to both the large resistance of the war and then into the anti-war movement when people felt it wasn’t going to be them dying anymore. And that’s that greed, that self-interest is what we have to struggle against.

[00:13:08] John Q: Wrapping up the community discussion at the Metro Theater, film director Judith Ehrlich.

[00:13:13] Judith Ehrlich: I think that one of the things this small group, and yes, it was a small group of people, but they are still at it. Almost all of them that went to prison until their dying day have been activists and still involved in the movement. And it wasn’t just because they were facing the draft, which they were, and that motivated them to think about it and to be committed for life. So that’s been really wonderful for me to get to know all these wonderful humans who are still at it and working hard to make peace.

[00:13:45] John Q: Judith had an observation about the Eugene audience.

[00:13:48] Judith Ehrlich: It sounds like a Berkeley audience to me. (Question!) I’ve got to say, you guys, you guys are so opinionated. My God.

[00:13:59] John Q: Anne Ehrlich O’Brien, Kara Steffensen, and Jim Anderson also spoke briefly about their work with Beyond War Northwest. For the next documentary screening and discussion, see EncircleFilms.org.

(With DJ Suss D at the Metro)