Paramilitary groups, cartels expand war on Indigenous peoples; Zapatistas reorganize

16 min read

DJ Suss D: Dec. 31, 2023 marks 30 years of struggle for the Zapatista movement. Mexico’s demobilized guerrilla group prepared for the anniversary of its pro-Indigenous, anti-capitalist uprising in an impoverished southern region beset by drug traffickers and paramilitaries. Supporters from Mexico and Europe headed to the state of Chiapas for two days of events in the jungle at the invitation of the Zapatistas Army of National Liberation, or the EZLN in Spanish.

[00:00:30] Taking its name from 1910 revolution hero Emiliano Zapata, the EZLN appeared the same day that the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, came into force—on New Year’s Day 1994. Many in Mexico at the time feared free trade with the United States would crush traditional lifestyles and farming.

[00:00:53] The guerrillas won over sympathizers well beyond Mexico’s borders, notably in Europe. At the time, the movement used the fledgling internet to share its press releases in several languages. A peace pact was signed in 1996, but the EZLN said its demand for constitutional reform that would guarantee its autonomy was never met.

[00:01:14] The Zapatistas retreated into mountain communities where they formed their own autonomous health and education systems.

[00:01:21] I spoke with Tonio, a local (Eugene School District) 4J schoolteacher who studies the Zapatista movement. He was in Mexico during last winter’s break. I asked what neoliberal policies have done to Indigenous people.

[00:01:35] Tonio: I grew up in Mexico and have a very strong Mexican culture. We can say that we really have a community and family way to make your living. And you can make a lot with little. And this is—I know we often don’t talk about it, but this is a very cultural use and abuse of our ways to do things. Like we can say, ‘Yeah, those Mexicans over there don’t need $17 a day, they can just take $1 and they should be able to live with that and they’re happy.’

[00:02:03] And that this is just an abuse of our cultural ways to go and just assume that we don’t want all the modern things that we could have access to and live with that benefit and with those goods that we persistently want.

[00:02:18] DJ Suss D: But it’s taking advantage of your simple way of life (Absolutely, yeah) to exploit you.

[00:02:23] Tonio: I think that people all over in Latin America, they vote for whoever they think might do better for them. However, politicians in Mexico are very influential and the U.S. and corporations have a lot of resources and money invested on these parties and these political groups and economic nucleus.

[00:02:41] So they are consistently investing money the way they invest here in lobbying and a group could be given money to a group of representatives to make law happen, and it’s legal. And in Mexico, it is not legal, but they would found or make projects where the politicans could benefit and this is the way they get to make it work.

[00:03:03] So, while Mexicans are voting for people they believe they will do their best, the politicians are also responding to the pressure of economic projects and politicians. And even institutions like the U.S. State Department and like the U.S. Army is also funding different projects in Mexico for security reasons or for strategic reasons that are like almost obligatory to our countries.

[00:03:35] DJ Suss D: International Monetary Fund loans, too. To pay those loans back, they have to do export, and there are also austerity programs.

[00:03:43] Tonio: And they have to make this into law. And even if we vote against it, they will come around and say, we have to do this because we have this obligation, so we have to respond to it.

[00:03:55] That’s an interesting thing about the Zapatista movement. Like, they do have an army. However, the army, after they agree with the Mexican government, they were on a truce. They have not gotten the army out of their camps, whereas the Mexican government is consistently patrolling with their army everywhere, all the time, by air, by land, and by water, in Zapatista land those titles were being taken, those lands were being taken away illegally.

[00:04:26] And when they recovered the land, they were able to say, ‘Hey, this is our land, so we have the titles. It was not ever yours, so we are just going to take it back.’ But that is not everywhere, but it is in the case of Zapatistas.

[00:04:40] I would say that before 1994, Mayans in Chiapas were somehow self-sufficient, but also they were very left out of all Mexican benefits.

[00:04:52] So everything that the Mexicans were getting as benefits from the development of their country as it is from since the 1930s—which Mexico really developed a lot in the first 40 years of independence and self-sufficient growth after our revolution in the 1920s.

[00:05:10] So they, after the power revolution, we had an actual social government for the first 15-20 years, and they built institutions that created education, health, different micro-production and industry that was growing rapidly from the first 30 years.

[00:05:28] None of this reached out and got to the Mayans or the Zapotecs or any of the native communities in all Mexico. By the late 1980s, in Mayan land, there were families losing their newborns out of diseases that nobody else were losing their kids, and that this is one of the reasons why they decided to go on the uprising, because it was, they were getting to the edge of the resources.

[00:05:56] I think it’s very characteristic for the Zapatista movement that they start with a community way to work, and where there is representatives and leaders and there is not really someone that could make a decision above everybody else. And this is something they took from the communities, like these were Mayan communities or Zapotec communities and other states that work like this way all the time since ancient times.

[00:06:24] And when the first outsiders got to the Lacandón Jungle in the late 70s, early 80s, and they were trying to learn how people was about going on finding their, looking for their rights, fighting for their rights, they moved from the Marxist model and the way to create groups of people working together towards this, they learned that they could not impose decisions on them.

[00:06:53] The more they responded to the natural way they organized, the more they were able to reach out and bring more people into their organization.

[00:07:03] And soon enough, people in the organization took control of the movement as it is. So although there is a few years like Subcomandante Marcos, Subcomandante David that are somehow outsiders—David is Mayan, but he went to school and everything, he went to college and they did—they cannot take decisions over the entire base of their communities.

[00:07:26] DJ Suss D: So, and what that means is that decision, what they found was that decisions made by the community tended to stick, whereas decisions made by a hierarchy did not.

[00:07:36] Tonio: And also by community doing an actual process where things are going to get done and because people are committed to it. And people said, ‘What can we do based on looking at this? This is what we can really do. This is what we commit. We’re going to make it happen.’

[00:07:51] All Native peoples in Mexico have practices that have been there for hundreds of years using natural resources to take care of their health. And when they stopped working with the Mexican health system, they started building their own clinics.

[00:08:10] And these clinics at first were mostly responding to immediate needs; that was with conventional and allopathic medicine. And then slowly they were forming health promoters that were collecting the knowledge of their own people to create a large set of different remedies for medicine of first intervention.

[00:08:35] Of course, there’s needs like when there’s surgery or there’s major need of intervention, they really need to go to that level of medicine, which they have also been able to build in some of those clinics.

[00:08:49] Especially in communities that are really hard to get to, solar panels are popular and in Zapatista area after the uprising, they move into building many different micro-power plants, hydro-micro power plants, solar production of power in micro-situations.

[00:09:10] They will, in communities that they have no power at all, they will bring a solar panel and some batteries to use to light up the basic areas in the communities.

[00:09:20] In Zapatista area, it is a popular practice as long as they have the resources or the solidarity funding for it, solidarity funding for it, they will get certain number of panels for central normal families and they have solar power for this purpose.

[00:09:37] Being self-sufficient the Zapatistas work in many different levels. The way they all—they work in their communities and their families, but they also work in state reform. They also work in national reform. They also lobby and or have been present in multinational discussions about ‘How can we make this different?’ with people that are like them, but also with people that are not like them.

[00:10:01] And also, I think that the reason people are looking at it is because it offers possibilities to people to organize and to look for self-sufficiency and connect with other projects and other movements that are looking for the same.

[00:10:16] There’s definitely a model for resistance and resilience and showing that it is possible with certain amount of force to take control of your I believe to be autonomous and self-sufficient and resist the progression of neoliberalism and policy that tends to destroy other ways to be.

[00:10:39] And it is what happens when the communities organize and are really, they’re expanding their ability to create and build co-ops, social projects, political power in a way that the local governments need to redress how they are doing public policy. And when this happens, these really drastic tactics have come to set the pace of how to respond.

[00:11:06] DJ Suss D: In June 2023, the Zapatistas issued a statement that was signed by more than 800 international organizations and more than 1,000 leading political and cultural figures, including U.S. intellectual Noam Chomsky, actors Diego Bernal and Daniel Giménez Cacho, director Alfonso Cuarón, and writers Guadalupe Nettel and Gabriela Jauregui.

[00:11:30] The statement in support of the Zapatistas calls out the rise of paramilitary attacks against the autonomous community and the impunity with which they are met by both the state and federal government.

[00:11:43] Chiapas is on the verge of a civil war with paramilitaries and hired killers from various cartels fighting for control of the territory.

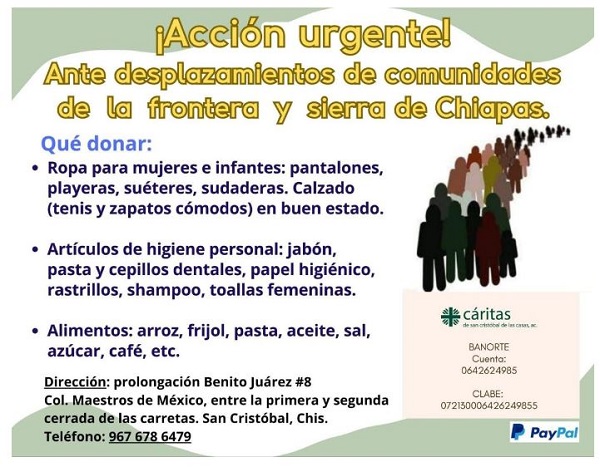

[00:11:51] According to a May 2023 report from the human rights group Frayba, Chiapas has become overrun by organized crime and armed groups with evident links to government and companies. The document highlighted the same problems raised by the allied groups: forced displacements, arbitrary detentions, torture, attacks on human rights defenders and journalists.

[00:12:14] According to Frayba, this is taking place during growing militarization, state and para-statal counterinsurgencies against the EZLN. There are 147 military camps close to their communities and the efforts of surrounding peasant and Indigenous movements. Tonio told me about the Acteal Massacre.

[00:12:35] Tonio: And after that what the Mexican government started is because they could not, there was no open fire, they started a low intensity war, which is used a definition to invest money in the communities in a way that takes base or families from the Zapatistas—

[00:12:54] DJ Suss D: Divide and conquer.

[00:12:55] Tonio: Divide and conquer. So they would offer money in many different ways and not necessarily in a productive or things that people were asking. They would just give money that before would not get to the communities. And the paramilitary would also invest money into paramilitary groups that would organize and terrorize the communities.

[00:13:18] After their uprising, they recovered land and they were able to establish a baseline on areas where they could rebuild their economy and their production. And they have competed with the development of counterinsurgency and low-intensity work for the last few years.

[00:13:41] In the last five years, maybe, the low-intensity work along the cartel has really made it very critical for anyone who is not in these two groups. You are either cartel or you are either against the organized people. You are benefiting from this. If you are neutral or you are Zapatista, you are really running out of resources and being pressured by this violence and lack of resources.

[00:14:10] And December 1997, a community of a religious community called Las Abejas was praying, hoping for the paramilitary to stop attacking and displacing communities in the last before that Dec. 22, 1997, many families were displaced from their communities because they were neutral.

[00:14:33] But so this were families that were not joining the paramilitary, not joining the Zapatistas. And the paramilitary, in a repression to this, they decided to attack and pressure these communities in displacing from their own communities. So they will come to the communities, shot their guns, set on fire houses, wood. Some people were killed. So the communities, the families slowly were moving away from their own land to a center called Acteal.

[00:15:06] So they were and that morning they were praying, hoping for peace. And while they were praying, a group of paramilitary came and committed a massacre. Dozens of Mayans from Las Abejas were killed in a very cruel way, following the practices of paramilitary in Central America. And after that, much more presence of international support came to Chiapas trying to prevent this to happen again.

[00:15:36] However, that set the pace of what the low-intensity war would be when it was not working. So when the low-intensity war doesn’t work to pressure a community, they would definitely move into more effective open fire or violent tactics.

[00:15:54] DJ Suss D: From June 19-22, 2023, members of the organization of Coffee Growers of Ocosingo (or Orcao) carried out a series of attacks that put three Zapatista communities at risk: Emiliano Zapata, San Isidro, and Moises and Gandhi, which are part of the Moises and Gandhi region, and are located in the municipality of Ocosingo, Chiapas.

[00:16:20] In addition to armed attacks, plots of land, or the family bases of support of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation work, and the plot attached to the autonomous secondary school, which is located just 50 meters from the houses of Zapatista’s families, were burned. This has been documented by the Good Government Council, New Dawn in Resistance, and Rebellion for the Life and Humanity, Caracol 10 “Flourishing the Rebel Seed,” with headquarters in Patria Nueva, Chiapas.

[00:16:48] The EZLN statement argues that the Orcao attack is part of the systematic dispossession of lands controlled by Zapatistas and other Indigenous communities. According to the group, this is happening to make way for government projects such as the Sembrando Vida, an initiative from López Obrador that provides economic funds in exchange for certain types of crops like fruit trees or timber.

[00:17:12] Programs such as Sembrando Vida and other similar projects foster confrontation between communities historically deprived of their lands and their rights. Reads the document, which says that these projects are used as mechanisms of political control and bargaining chips to allow organizations like Orcao to access supposed benefits that these programs provide at the cost of the theft of the Zapatista Autonomous Recovered Lands.

[00:17:37] Actor Daniel Giménez Cacho expressed Zapatista security concerns. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation, which has maintained peace and has developed its autonomous project in its territories and which has tried to avoid violent clashes with paramilitaries and other forces of the Mexican state, is constantly harassed, assaulted, and provoked, he said.

[00:17:58] Since the end of the 20th century up until now, the EZLN has opted for a political struggle along civil and peaceful paths, despite the fact that their communities are attacked with bullets, their crops set on fire, and their cattle poisoned. Despite the fact that instead of investing their efforts in war, they have done so in building hospitals, schools, and autonomous governments that have benefited the Zapatistas and non-Zapatistas.

[00:18:23] Governments from former Mexican President Carlos Salinas to (current President Andrés Manuel) López Obrador have tried to isolate, delegitimize and exterminate them. “This war is against the Indigenous peoples of this country,” Carlos González García of the National Indigenous Congress added at a June 2023 press conference. “What’s happening in a shocking way in the Chiapas region, where the Zapatista communities are located, is part of a whole policy and a whole reality that our country has been experiencing for years.”

[00:18:51] Militarization has been growing since 2018, the year that Obrador came to power, like never before. The activists argued that programs such as the Sembrando Vida are used as a tool for control in regions where the federal government promotes strategic megaprojects such as the Maya train or the inter-oceanic corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

[00:19:16] These same complaints were raised at the beginning of May 2023 when 700 of the guerrillas met in a Zapatista community in the city of San Cristobal de las Casas as part of El Sur Resiste (The South Resists) brought together diverse communities threatened by the Mexican government’s megaprojects.

[00:19:35] Experts agree that the high-tension situation in Chiapas is of great concern. According to an opinion column in La Jornada, a newspaper close to the Mexican government that has distanced itself from the Zapatista movement, Chiapas is a powder keg that can explode at any moment.

[00:19:51] At the beginning of November, the Zapatistas announced the end of their autonomous civil systems and the indefinite closure of their cultural centers due to what the EZLN called complete chaos in Chiapas due to the threat from disorganized crime.

[00:20:07] There are blockades, assaults, kidnappings, extortions, forced recruitment, shootings. It’s said Mexico’s two main crime groups, the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation cartels, are fighting for control of the region, according to experts. Armed hooded men believed to be members of the Sinaloa cartel were seen marching to applause in Chiapas in a video broadcast last September.

[00:20:29] The federal, regional, and local military and police forces are not in Chiapas to protect the civilian population. They are there with the sole objection of slowing down migration, the Zapatistas said. Despite a thriving manufacturing sector and a growing middle class fueled by massive trade with the United States and Canada, today more than a third of Mexicans still live in poverty, according to official figures.

[00:20:54] Hopefully the Zapatista message of ‘lead by following’ will not be lost forever.

[00:21:00] Tonio: And something that is important to take from the Zapatistas is the way they think about power. So they are not saying that we don’t, it’s not that we don’t want power, it’s not that we don’t want the presidency or we don’t want to be a political party, it’s that we want to make sure that power is used differently. And power is not just to benefit you, but it’s to benefit everyone.

[00:21:23] So they’re asking for to have everything for everyone and nothing just for themselves. If following this policy, you can do your regular work as a doctor, as a teacher, as a district director, as a school director, school principal and use your power in a way that everyone is empowered and from the teachers, the students, the families.

[00:21:51] And then we modify the way our institutions are functioning now. It’s likely that we’re going to start creating different policy and we’re going to be able to respond with ease to other efforts in other parts of the world. And we could connect to them. If you are a interested teacher, you can definitely connect to the educational projects there.

[00:22:14] If you are a farmer, you could connect to the projects there as well. And the more we learn and the more we bring Their voices into places with the otherwise there would not be heard or known, the more we could connect, create awareness and possibilities to really interact and make these connections happen.

[00:22:38] And we are disconnected from not just Zapatistas but also also organizations in Northern Mexico, where many people from all over Mexico and Central America are just living in shackles to produce tomato. But they’re organized and they’re looking for rights for themselves, but we are fully disconnected to them.

[00:22:57] The more we learn about them, the more we make our local spaces aware and able to respond to our own needs, we likely will be able to connect to those needs as well.

[00:23:09] Based on our talk today, based on the Zapatista movement and the Zapatista phenomenon, we should be trying to multiply different ways society could work and allow every different society to build policy and practices that benefit everyone in the process, not just the CEOs, not just the managers or the directors, but every single one has access to the benefits and the goods that every process brings to the community.

[00:23:40] Whereas here it might be some efforts in several market local collectives, they should also at the same time learning from other efforts in Chiapas or Oaxaca or Nicaragua that might be really interesting for them in the way things make work that benefits everyone and allows them to continue develop their human selves as a whole, not just part of them.

[00:24:09] Definitely anything you could do to modify local policy in a way that again it doesn’t dehumanize us and is benefiting everyone here could be shared with other places.

[00:24:24] DJ Suss D: Where you’re talking on low-power FM radio here, how, what did radio, what part did radio play in the Zapatista movement?

[00:24:32] Tonio: Well, radio was very interesting phenomenon in Mexico.

[00:24:37] For me, I was a communications major and I wrote a little, a few different scripts for propaganda for the social efforts. But also community local radio was the only way for Zapatista communities, in many times, even now, to be able to communicate and learn about what was going on. Radio was critical and still critical in small communities and small farming communities in Mexico and Latin America.

[00:25:06] DJ Suss D: For KEPW News, I’m DJ Suss D.

DJ Suss D is host and producer of the program “Talk Is Cheap,” which airs every Saturday at 4 p.m. on KEPW 97.3 FM.