Oregon’s land use laws are being used to worsen inequality

5 min read

by Marty Wilde

Anti-growth advocates are abusing Oregon’s land use laws to exclude low- and medium-income people by preventing the construction of affordable housing.

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Oregon instituted a land use system of compact growth, encouraging denser housing within city limits to prevent sprawl and preserve farm and forestlands. Legislators wrote public input into the process to balance the needs of growth with those of livability.

Today, the pendulum has swung from a government that championed industry over people to one where people use the land use system to prevent all growth.

Despite famously saying “Don’t move here,” Gov. Tom McCall did not oppose growth. Rather, he sought to regulate it. He fought against policies that made Oregon a “hungry hussy, throwing herself at every stinking smokestack that’s offered.” (As a former journalist, he had a way with words.) He supported a system that provided “affirmative assistance” to those in need. From this perspective, the anti-growth sentiment currently preventing the construction of housing is not a continuation of Tom McCall’s sentiments, but a perversion of them.

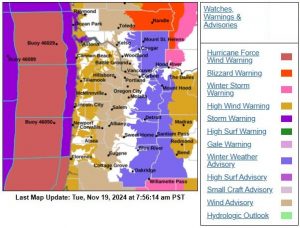

Oregon uses Urban Growth Boundaries to regulate the geographical growth of cities. Cities must keep an inventory of residential, commercial, and industrial land within the UGB sufficient to provide for the next 20 years of projected need. Cities develop UGBs through a lengthy administrative process that includes public input and that can take up to 10 years.

North Plains is a community of about 3,500 people located 18 miles northwest of Portland. With a predicted doubling of its population over the next 20 years, the city government of North Plains expanded its UGB to include more residential, commercial, and industrial land. The expansion would permit North Plains to change from a bedroom community to one that is more self-contained and less car-dependent.

To prevent the expansion, anti-growth advocates referred the matter to a May election, which typically has low turnout. While the technical legal issue revolves around whether the UGB expansion is an administrative or legislative act, what is really at stake is whether the residents of a community can effectively veto growth altogether, overriding the state’s land use laws.

The Oregon Legislature removed the issue from the ballot, supporting planned growth over a local veto. Some North Plains residents have now sued to prevent the UGB expansion. A court has overridden the Legislature for the time being, keeping the referendum on the ballot until a full trial is held. Effectively, this allows local voters to override state land use laws to exclude new residents, something never envisioned by the founders of Oregon’s land use system.

Witnesses often begin their legislative testimony with, “I am an (n)th generation Oregonian!” When I heard that, I generally took it as a statement of their love for our state, but I also always thought, “What did you have to do with where your grandparents were born?” No matter how long a family has lived in Oregon, they do not have the right to exclude others. If it were so, I imagine quite a few Native Americans would love to have us leave their land and go back to where we came from.

Americans have a constitutional right to move between the states. Indeed, our modern economy depends on the labor mobility this right allows. However, we have reached the point where that constitutional right is being frustrated by actions of existing residents who wish to prevent growth. While often cloaked in the garb of environmental protection and an antipathy for “greedy developers,” their motives often include the more prosaic desire to drive up housing values. Indeed, homeowners benefit far more from the housing shortage than developers do from construction.

Oregon’s land use system already allows substantial public input in the zoning process. In recent years, this has come in the form of opposition to denser housing in the middle- to low-income range. While owners benefit financially from upzoning, neighbors oppose it as “changing the character of their neighborhoods.” As a result, the densification of the housing stock designed into the system to protect farm and forestlands rarely happens. Our cities often remain essentially suburban in nature, even when they are close to the urban core where the densest growth should occur to optimize land use.

The outcomes of these policies of exclusion are uniformly inequitable. Out-of-state people with modest incomes cannot move to Oregon, even to fill our urgent labor needs, because the growth in the cost of housing has far exceed the growth in wages.

For instance, between 2010 and 2022, wages grew 56% in Lane County, but housing costs grew 99%. Wealthier out-of-staters can move here, of course. When they do so, they further drive up the cost of housing and often displace poor and minority residents from older housing as they rebuild or renovate housing. Portland’s Albina neighborhood offers a good example of this trend.

To be fair, the causes of our housing problem aren’t all from NIMBYism. Because of the subsidy provided by the mortgage income deduction, Americans put more of their savings into their homes than almost any other people in the world. While the percentage of taxpayers taking the deduction fell from about 20% to about 8% after the 2017 tax reforms, the drive for homeownership strongly persists in our culture, even when it no longer makes economic sense.

Oregon’s property tax reforms in the early 1990s worsened the problem by shifting more of the costs of infrastructure growth onto new construction, a sharp turn from the historical sharing of these expenses with existing residents.

But the core of the problem remains a culture of exclusion. While most of us have joked about the “Californication” of our state, the reality is that, in fighting the construction of the housing we need, we are creating a state with the same gaping inequalities that afflict California.

If, instead, we wish to preserve the natural environment and remain true to our progressive values, we have to build the housing our low- and middle-income neighbors need. We all want Oregon to be a shining city on a hill. Let’s make it one where the gates are open, not closed.

As Tom McCall also said: “Enhancing the quality of life is the lodestar of this Administration. Inherent in this is the kind of tax structure we have; the quality of homes in which we live; the cleanliness of our air and water; and whether we provide affirmative assistance to those less able to assist themselves. True quality is absent if we allow social pollution to abide in a pristine environment.”

Marty Wilde represented central Lane and Linn counties in the Oregon legislature. For more of his Letters From a Recovering Politician, subscribe at https://martywilde.substack.com/subscribe.

Image: Tom McCall statue in Salem Riverfront Park courtesy Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives.