Dad, why doesn’t the US have direct democracy?

4 min read

by Marty Wilde

My son recently asked me why the U.S. isn’t more democratic. After all, we set up the current system when the fastest mode of land travel was a horse. Now, with the ubiquity of cellular phones and the internet, people could easily vote every day. He concluded his question with, “Are people just too stupid?”

Despite the flippancy of the question, it deserved a thoughtful answer. As a trial lawyer, I always found juries, a proxy for voters here, to be quite thoughtful. I didn’t always agree with the juries’ decisions, but those groups of twelve random citizens tended to come up with fair and reasoned results based on the evidence presented and the rules governing their decisions. Some jurors were well-educated, others not, but I never had occasion to believe that they were unintelligent or failed to take their job seriously.

My conversations with voters confirmed this impression of thoughtfulness. Mostly, they wanted to see if I shared their values or could be convinced to do so. If they thought I did, they would often tell me about an issue of particular interest to them. These conversations helped me understand my constituents and helped them trust that I would educate myself and vote according to our shared values.

I explained to my son that we continue to have a representative system largely because not everyone wants to keep up with politics as much as frequent voting would require. They want to be able to trust the politicians they elect to know the issues and vote in accordance with the values they share on most issues.

Conversely, they absolutely want the right to weigh in on the big issues through the initiative system, especially when they feel that politicians are letting their own interests diverge from those of their voters.

Too often, the only political communication voters receive from their elected officials is that designed to make them fear the negative, rather than soliciting their opinions about how to build a better future.

I tried to take this to heart. Two of my harder “no” votes were against bills supporting middle housing and some criminal justice reforms. While these issues were close to my heart, I knew that my voters did not yet support them. I owed it to those I represented to spend more time providing them the information they needed to either come to agree with the principles in those bills (or not) or to refer those matters to the voters for them to decide. No politician should ever believe that they “know better” than their voters.

The higher politicians go in office, the more difficult it is for them to remember this. Yes, voters can be misled, but, as often as not, the window for political hucksters and charlatans opens because politicians believe that the voters are “too dumb” to understand “what needs to be done.”

Most often, the people who politicians believe “know better” are—not coincidentally—the people who fund their campaigns. In support, consider the fact that, although four of five Oregon voters support campaign finance reform, it has taken decades to get even a weak bill through the legislature.

We see this hubris in other ways as well – prevalent nepotism in politics, hostility to open primaries, failure to prevent gerrymandering, and, most telling, the unwillingness to communicate openly and honestly with voters. When was the last time a candidate for a state office came to your door and asked for your opinion on the issues, listened carefully, and responded thoughtfully?

I once attended an international conference where I met a Canadian representative who served at a similar level. We discovered that I represented about 67,000 people. She represented about 1,500. We joked that, while I had to know my voter’s children’s names to earn their vote, she had to know those as well as the names of all their pets.

While it can be difficult to reach the voters, fewer and fewer elected officials make the effort. Most politicians at the state and federal levels represent too many people to knock on every door, but many don’t knock on any at all. When in office, they often stop canvassing and rely exclusively on staff to reply to correspondence from voters.

I’ve always respected Mayor Lucy Vinis for her attempts to contact her voters at their doors and tried to follow her example. Some pols don’t even bother with a newsletter or town halls. With so many gerrymandered, non-competitive districts and negative political polarization, politicians have little incentive to communicate. And, in that, we see the root of the current loss of trust between the elected and their voters.

We continue to have a representative system, rather than a more directly democratic one, because voters want to be able to trust their representatives to educate themselves, communicate with voters, and vote in accordance with their shared values.

We have failed by allowing politicians to game the system so much that they care more about their funders than their voters. With the long overdue passage of campaign finance reform this year, we took a small step toward remedying that. We still have a long way to go.

Marty Wilde represented central Lane and Linn counties in the Oregon legislature. For more of his Letters From a Recovering Politician, subscribe at https://martywilde.substack.com/subscribe.

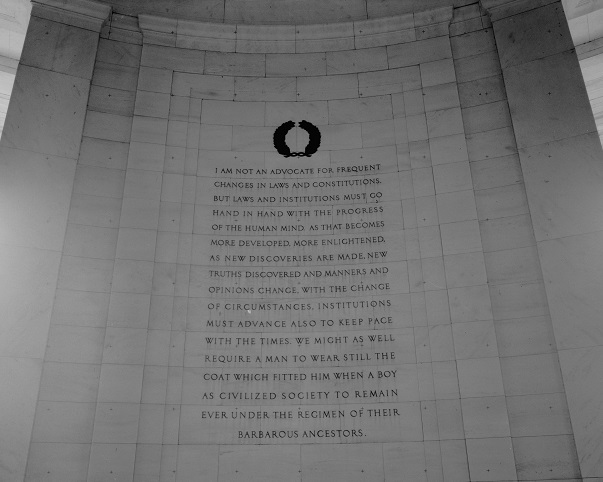

Image of northeast panel in statuary chamber, Jefferson Memorial, East Potomac Park, Washington D.C. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.