County warns of whooping cough outbreak

13 min read

Lane County Public Health declared a communitywide outbreak of pertussis, also known as whooping cough. Speaking to commissioners May 7:

Eve Gray (Lane County, Health and Human Services director): Pertussis or whooping cough, as many people know it, is a bacterial infection. So unlike many coughing illnesses, which are often viral in nature, this is a bacterial infection.

[00:00:23] And what happens is the bacteria cause inflammation in the airway that causes irritation, which then causes paroxysms or fits of coughing, often characterized by coughing and feeling like you can’t breathe anymore, and then suddenly you gasp. And then with an airway that is maybe inflamed and somewhat constricted, when you gasp and bring that air in rapidly, you end up with a whooping sound. So that is how the disease has been given its name of ‘whooping cough.’

[00:00:54] It is transmitted similarly to other types, to viral illnesses. So again, it’s bacterial, but transmitted in the same way, by droplets from the nose and throat and coughing close contact. The incubation period is longer than for a lot of diseases, so seven to 10 days is average, but there’s a pretty significant range: four to 21 days. That means, you can be out a little ways from exposure by the time you begin to show symptoms. And then once you show symptoms, your infectious period has started and the infectious state can last up to three weeks or after the first five days on antibiotics.

[00:01:40] So we do treat pertussis when we identify it, particularly if we identify it early. The thing about pertussis is often when you start coughing, you think, ‘Oh, I just have a cold.’ And you don’t show up to the doctor until two or three weeks after you have been coughing and it’s not getting better.

[00:02:02] And with pertussis, of course, you may have been spreading pertussis in the community for two or three weeks before you went in to get help. So one of the pieces we want the community to be aware that there is an outbreak right now. And if you start having fits of coughing or a family member has fits of coughing, we would encourage you to go in and get tested to make sure that you are not, that this is not affecting you and you are not spreading the illness within our community.

[00:02:28] Vaccines are the best protection that we have. DTaP and Tdap: The DTaP has a little bit stronger dosing, which gets immunity going, and then the Tdap vaccines have a little bit lower dosing to renew immunity for folks. So there are, the CDC has the vaccine recommendations.

[00:02:48] I encourage anyone who has questions to call your doctor or look at this and, or look at the CDC guidelines for vaccination. We do recommend that if you are not up to date, anyone in the community could or should get up to date on your vaccination. Now that is particularly important for pregnant women and anyone who anticipates being around babies.

[00:03:12] Babies are the ones who are most at risk of severe illness, hospitalization, and/or death related to pertussis. So if you will have any contact with a baby, please make sure that you are up to date on your vaccine. And of course all the things: cover your mouth when you cough or sneeze; wash your hands; stay home when you’re sick.

[00:03:31] John Q: With the county commissioners May 14:

[00:03:37] Dr. Patrick Luedtke (Lane County, senior public health officer): Early on, we only had one school involved, and then we had a couple schools and a university. And then we had a few households, and they were not epidemiologically-linked. And we’re probably approaching an inflection point where there’s more transmission out in the community, not limited to simply one or two households or one school or two schools. We’re up to 39 cases that we put in the confirmed presumptive bucket. We do have a couple suspect cases that may become confirmed, we’ll see.

[00:04:02] Yesterday we got a new baby, five months old, which is always sad for whooping cough.

[00:04:07] Many of us in the adult age, we get whooping cough, we have a chronic cough, so-called ‘100-day cough’ and we’re otherwise fine at the end of that. It’s babies who get severe disease and die from this disease, so that’s concerning to see a five-month-old.

[00:04:20] We’re not alone in this. The state has many cases, most of the cases are in the younger age group, adolescents and young adults. That’s pretty common. We see immunity wane in this vaccine. It’s not one of our best vaccines. We sure wish it was better, but it’s not. That’s the vaccine that we have.

[00:04:35] Some of you will remember a very large outbreak in 2018, hundreds of cases here in Lane County. We think that early action by our partners at the schools and by the households and keeping people safe have really made a difference so far. We were expecting perhaps some higher numbers, but I think we’re being both lucky and good at this particular time, which is nice to see.

[00:04:54] It’s a little disconcerting though, that it was very predictable. Those of you who have been reading, following some of our messages to the clinical community or the lay community. We knew that we were entering a risk time period. This is a cyclical condition and even though people are still to some extent wearing masks and perhaps decreasing their risk a little bit as some of the pandemic residual, we’re still a community at risk.

[00:05:16] This is not a great vaccine. Its immunity wanes over time and we knew it was coming. And it’s interesting to see because it’s really almost exactly the same time in 2018—first cases in March and you know, so next escalation in April. We had a fallow period, 20, 21, 22, 23, and then a slow increase, and that’s where we are today, a bit over 100 as a statewide total, and that number will surely go up unfortunately.

[00:05:42] So overall why pertussis, why now? I alluded to a few reasons and I’ll just go through them a bit more in detail. The first is a cyclical nature. And every three to seven years or so (unless there’s a pandemic in between) we typically see a new cycle of whooping cough cases. In the ’03, ‘04’, ‘05 timeframe, we had an increase in cases statewide, and then six, seven years later, it happened again. And if you add six years to that, you get 2018. We had a lot of cases as I alluded to, around 300 cases that were confirmed or presumptive.

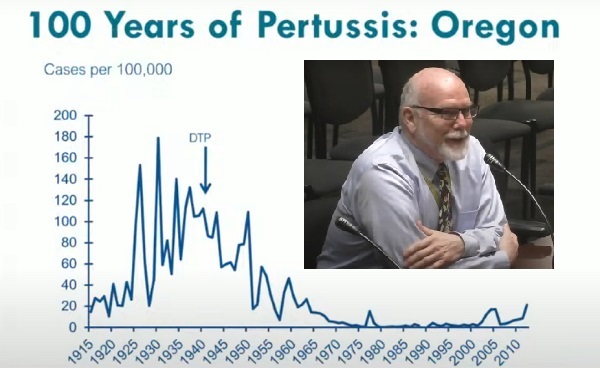

[00:06:12] So, pertussis has been around for a long time. We really don’t know how long, but certainly perhaps hundreds, if not thousands of years. And this is Oregon data for the last 100 years: Somewhere in the mid-1940s, we got the first trivalent, tri vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis. We put those three agents together.

[00:06:30] And of course, if you think back to this country in the ’40s, not every school system, not every clinic was giving us vaccine, then it was a slow rollout. But by the time we had a significant rollout, we didn’t eliminate the disease, but we went from a couple hundred thousand cases per year down to under 10,000. So we had school requirements for tetanus and diphtheria in the early ’80s.

[00:06:51] And then we had the acellular pertussis vaccine. I’ll spend a moment on that. The ‘a’ (in DTaP) is ‘acellular.’ The DTP vaccine was a very good vaccine. And the pertussis component had a lot of antigen in it, which means it provoked a pretty significant immunological response. Unfortunately, too much antigen sometimes causes things that parents, like a febrile seizure, don’t like to see. And while infections can cause febrile seizures, any insult can cause it in some kids if they have a lower type of seizure threshold.

[00:07:21] So the vaccine was reformulated. Instead of using the whole cell of the bacteria, they chose only three particular chemicals. And we got an acellular vaccine with just those three chemicals. That’s a good thing in terms of side effects. It’s not quite as robust for immunity.

[00:07:36] So after being flatlined for a while, in the 2005 timeframe, we had a pretty significant outbreak as immunity waned from that less-effective vaccine, and then six years later, we saw it again.

[00:07:46] We’ve got a new test, polymerase chain reaction. You’ve heard about PCR a lot during the pandemic, the PCR test for COVID, very remarkable technology, but we finally got that for pertussis.

[00:07:57] And then school requirements in Oregon occurred around the Tdap vaccine for adolescents, typically age 11-12 is when that’s recommended for a booster.

[00:08:06] So the first reason we’re seeing it now is a cyclical nature. The second reason is, we’re a community at risk. Now, our vaccines didn’t plummet during the pandemic, but it’s really hard to give a vaccine over a computer screen when you move to telehealth. That’s just a challenging thing to do. Every vaccine dropped a little bit during the pandemic for kids in this state. except for hepatitis B, which was essentially stable from 2019 to 2022.

[00:08:29] We don’t quite have the updated 2023 data confirmed. The preliminary data shows that it probably dropped another 1-2% for most of the vaccines. Again, it didn’t plummet, but it dropped a little bit. It was harder during the pandemic to get vaccinated if a parent or guardian wanted to get their kid vaccinated. It’s just more difficult during that time. And we’re seeing that data showing that the vaccine rates have dropped a bit. So consequently, we’re a community at greater risk.

[00:08:51] So decaying immunity. I mentioned the fact that we had the wholesale vaccine, which was really quite robust, gave good immunity for a long period of time, but again, too many side effects. We got the acellular vaccine, and we think, somewhere around five years or so out from the vaccine, it’s almost a coin toss of whether you’re immune or not. The immunity decays fairly quickly.

[00:09:13] So there have been questions for some time: Do we get a better vaccine, or do we have a booster dose, like we do with tetanus every 10 years? We recommend you get a tetanus booster. Nowadays, you can get your 10-year booster for tetanus and include the pertussis component. You can get that Tdap vaccine.

[00:09:30] But there are a couple of candidates that are in the pipeline for a better whooping cough vaccine. Perhaps they’ll come to fruition. We’ll see.

[00:09:39] So where do kids get pertussis? Many studies show that 50- 60% of kids get it from their primary family: so mother, father, sister, brother. Not everybody does. You know there’s a few different types of or serial groups of pertussis circulating and when we do that deep molecular testing we find out that this particular child has it and it’s different than the one that the sibling has. But most of the time it comes directly from a first-degree relative in the same home.

[00:10:05] We are not going to have tens of thousands of cases of pertussis in Lane County. We’re probably going to have hundreds. And we want to make sure that the community is ready and is able to prevent the risk to themselves and their family members and their loved ones.

[00:10:21] In a typical year in this country we have, oh, between 10 and 30 deaths from pertussis. That’s not many for an entire country. Almost all of them are babies—infants typically three months and under in age, they cannot be protected. Their immune system is not able to make immunity and they can get some immunity for mom if mom got the vaccine in her third trimester, which is the recommendation. And those children are almost always protected, but that doesn’t always happen. Some people don’t have access to health care and the vaccine.

[00:10:49] In Oregon, we had very, very few cases, as you saw on that 100-year timeline of pertussis, during the time, we had the DTaP, the DTP. And then when the acellular came out, we started to see that decaying immunity. And we’ve had those regular outbreaks every five, six, seven years now.

[00:11:05] The vaccine, again, you’ve heard me say it several times, is far from our best vaccine. We’d love it to be as good as the measles vaccine where two doses you get immunity and you’re immune for life. That is not this vaccine. It’s just a tough bacteria. But there’s still benefit even in an outbreak, there’s benefit of getting vaccinated.

[00:11:22] So I’m going to finish with this illustrative case. Sometimes in Public Health, we get accused of fearmongering. We really don’t like to do that. This is a kind of a scary case. So, we had a mom, healthy pregnancy, offered her Tdap booster vaccine during the third trimester, which is what we want every mom to get so the immunity goes to the baby when the baby is born. The baby is protected until their immune system starts to work.

[00:11:44] The mom decided not to get it for whatever reason.

[00:11:47] At 35 weeks of gestation, there was a question of whether she had some type of infection in the lining around the baby, the corioamnion. She did well in the hospital. She was sent home on day three. One day after discharge, the baby had some challenging breathing and they did a blood oxygen rate. It was greater than 94%, which is kind of the cutoff where we start to get worried in adults even. No cough and was sent home. Returned the next day with worsening breathing issues, occasional desaturation. That’s where you drop below that 94% level. The hemoglobin is no longer saturated with oxygen, so we call it desaturation.

[00:12:21] The testing was done for pertussis, wonderful thing. The word was out that pertussis was around, and the group tested the child. At 19 days old, presented to the local emergency department with an apparent life-threatening event, but while in the hospital didn’t have a cough. You know, little ones don’t breathe a whole lot, and sometimes if their airways are really full of inflammation and mucus and things, they can’t cough up much, but the clinical decision was to send the child home, and mom had a cough at this time now.

[00:12:47] Day 24: Respiratory distress and unfortunately stopped breathing and needed to be transferred to a tertiary care hospital; ended up in the pediatric intensive care unit. But continued to deteriorate, went on basically…where a machine breathes for you, was in the hospital for three months, discharged later, had a stroke and some other challenges.

[00:13:06] So overall case summary on that external, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, that external breathing, intubated for 75 days, had a stroke, seizures, all kinds of problems. Tdap cost at the time was $64. It’s a bit more now. And the hospitalization was about $1.6 million.

[00:13:23] And the five-year follow-up, unfortunately, the child is globally affected. The left-sided weakness, will probably never run a marathon, sadly, and all kinds of ongoing problems, especially with muscle tone, hypotonia.

[00:13:36] Sorry to end with a bit of a downer, but I wanted to make sure you know that even though the numbers are very small, where we see severe disease, you can have severe impacts. And this is why we push pretty hard when there’s outbreaks of this sort.

[00:13:47] Commissioner Heather Buch: My question revolves around day care centers. Now you had mentioned that the majority of this gets transmitted within the main primary family but knowing that little ones are often at day care centers and I think there was one or more that was affected in this so far, what do you suggest that they do? What are the steps other than to beware and to notify if you see any activity? But as you mentioned in this case, the little one didn’t necessarily have a cough, so you don’t always know what’s going on. So in our day care centers around here, how are we advising them, other than notifying parents to watch out for the symptoms?

[00:14:33] Dr. Patrick Luedtke (Lane County, senior public health officer): I can’t stress enough that I wish this vaccine were better, but we still want to recommend the products, the tools that we have. So the first thing is that, the primary prevention, to be vaccinated. And if you’re eligible for the booster, get your booster. If you’ve had your primary series, which is five doses—that’s a lot of vaccines. But the primary series of DTaP is five doses in little ones.

[00:14:58] And then in adolescence or in adulthood, if you miss the adolescence, you get your booster. So that’s number one.

[00:15:03] Number two is: We do want people to be ever vigilant for cough syndromes. And a cough is not always whooping cough. Of course, it could be asthma. It could be allergies. It could be heartburn even in some people with acid reflux, that can trigger the cough center. So we really want to make sure that people are vigilant for cough illnesses and those are really the big two.

[00:15:24] Now of course this is an easy bacteria to kill with just soap and water so washing your hands and such is a good thing. We rarely—in fact I can only think of once or twice in my career in public health where we closed down a facility or closed a school for this. We just don’t do that. Typically, by the time we get enough cases, the cow’s out of the barn, the cat’s out of the bag, whatever the metaphor is, and there’s just not value in that. In fact, there’s more harm. So the prevention side is really the most important.

[00:15:53] John Q: Lane County Public Health reports a communitywide outbreak of pertussis or whooping cough. For more information see their website, https://www.lanecountyor.gov/publichealth.