Sen. Golden proposes neighborhood wildfire cooperatives for better insurance rates

9 min read

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

by Sen. Jeff Golden

It’s a season of anxiety. Monday, July 22, legislators met online with the state’s top wildfire officials and they didn’t give us great news. In the last ten years, we’ve seen an average of about 650,000 Oregon acres burn each year. At this point, something like 680,000 acres have already burned. As I write these words, 27 large fires (defined as 100+ acres in timber or 300+ acres in grass/brush) are burning in the state, including four active megafires (each over 100,000 acres).

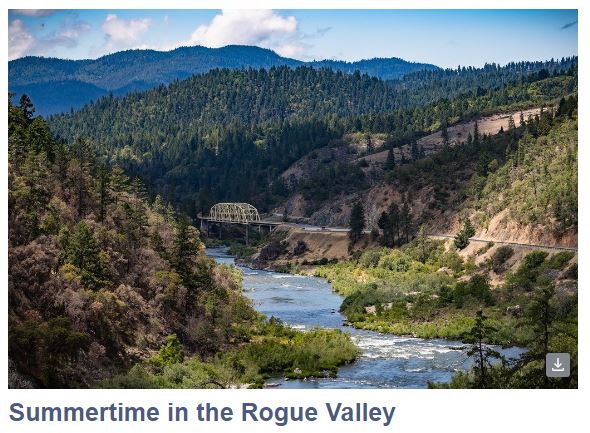

So we’ve already reached the numbers for a grimly extreme wildfire season, with at least two or three months of extreme wildfire danger still to go. This is the brutal reality of a landscape, shared with most of the western U.S., that’s getting hotter, drier and windier every year.

You may have read that a draft version of the statewide wildfire map, a second attempt at identifying Oregon’s most fire-prone areas, was released last week; here is a pretty accurate summary of where we are and how we got here. In the days since, I’ve heard from a few residents who remain unhappy or suspicious about the mapping process.

What I don’t want to do is suggest that people shouldn’t be upset about what the era of megafires has brought us, particularly in Jackson and Josephine Counties, with our extreme vulnerability to community-destroying wildfire. The awful toll of past fires, the struggles of friends and neighbors trying to build their lives back, the gnawing anxiety when winds whip up on hot evenings, the prospect of having to evacuate at any time, the orange-brown air that can make breathing difficult for weeks on end, the non-renewal or spiking premiums of insurance policies, the doubts about the wisdom of fully laying down roots here and what’s in store for our kids if we do—all of it is deeply upsetting.

I’m writing instead to respond as clearly as I can to concerns coming to my inbox this past week. I sponsored SB 762, passed in 2021, because I think it’s a path to improving our odds to survive the summers ahead of us, which will continue the fire-stoking conditions we live with today. The most common concerns sound like this:

“If SB762 is supposed to help with wildfires, where are the provisions in this bill to better manage the forests?”

While the wildfire map and efforts to fire-harden homes and yards gets about 98% of the publicity and public attention, they’re actually just one part of the overall SB 762 strategy. Other sections center exactly on forest management, with the largest investments our state has ever made in thinning out woody fuels that, after a century of complete fire suppression, are kindling today’s megafires.

The plan is to continue those programs, with the Oregon Conservation Corps (a youth-in-the-woods program), professional reforestation crews, and commercial and non-commercial thinning, for the next 20 years. You’ll also see the feds stepping up to much more fuel reduction in the national forests. We’re striving to coordinate our work with theirs in ways that make the most sense.

What we have to avoid is either/or thinking, as in: ‘The whole wildfire problem is the result of (pick one) climate chaos / poor forest management / more building and human activity in and near the woods / carelessness and criminal activity.’ We are grappling with all of these, and the breadth of SB 762 reflects that.

“We really don’t need your help. Oregonians have lived in the rural areas of Oregon for hundreds of years, why do we now need a map to tell us about the hazards?”

A lot has changed over those years. The number of people who have settled in and around Oregon forests has multiplied several times over in recent decades, greatly expanding the “home ignition zone” that is one of the two primary origination points (along with lightning strikes across the landscape) of these fires. And some recent forest settlers have a lot less fire awareness and experience than others.

The practical reality is that we don’t have nearly enough public resources to protect Oregon communities to the degree we’d like. We have to know which communities and neighborhoods are most vulnerable to disaster, and need the map to tell us that. Without it, we can’t intelligently deploy our limited resources—equipment, boots on the ground, expertise to help citizens become fire-ready, grants to those who struggle to make improvements.

None of us in government enjoy hearing that some people see the maps as a way to penalize people, or to gain more power over people’s lives. We’ll keep doing all we can to improve the maps, and make sure they’re used to help people and communities towards the goal of fire-readiness. But we can’t meet our core responsibilities of public health and safety if we toss them aside.

“Looks like you want public input, AFTER all decisions have been made. Not cool.”

It’s proved challenging to weave together wildfire science, the practical lessons of past fires, and meaningful public input—especially at a time when very few citizens have time to examine and digest dense material—all while under the gun to get programs in place before more fire comes to more communities. We’ve learned a lot about all this since launching SB 762, and we aim to continue improving.

The public input elements of our wildfire program include:

Rules Advisory Committees (RACs): All of the guidelines and rules in the program are produced with the guidance of RACs, which carefully include members from all sectors with strong interest in the outcome. Depending on the kind of rule, this typically includes the timber industry, conservation groups, small woodland owners, farmers, homebuilders, local officials, utilities, realtors, and private property proponents. We can’t expect public acceptance of the final product if we don’t have this kind of diversity to through the process.

The Wildfire Programs Advisory Council (WPAC): The WPAC is a group of nineteen concerned Oregon citizens who volunteer immense amounts of time to help us correct course as the SB 762 program unfolds on the ground. You can get an idea of the effort to cover the breadth of Oregon citizen voices with a quick glance at their website.

Meetings with local officials across the state: We directed the leaders of key agencies to personally present the draft maps and other program elements to the commissioners of all 36 counties in Oregon. Throughout 2023, they did that in public meetings across the state, inviting and receiving public input and suggestions that have influenced the direction of SB 762.

Direct citizen input: Right now we’re in a month-long period accepting input from anyone with views on the mapping or other aspects of the program. Deadline for comments is Aug. 18.

“This map is making it hard/impossible to keep affordable insurance on my home.”

Let’s start by acknowledging a hard fact: the loss of affordable insurance is turning the lives of millions of Americans upside down. The clear cause is the tens of billions of dollars in claims the insurance industry is paying out for the damage of climate chaos: hurricanes in the Southeast, tornadoes and flooding in the Midwest, wildfire in the West. The insurance model that has worked since World War II simply isn’t anymore.

Some people continue to believe that the SB 762 maps are one cause of their problem. This despite the fact that other western states without similar legislation are undergoing the exact same crisis, and the fact that the insurance industry had developed sophisticated hazard maps of their own for actuarial purposes before we started drafting SB 762. The providers of homeowners insurance in Oregon have all signed sworn affidavits that they haven’t and won’t use our maps for underwriting purposes.

Some residents have suggested that their agent blamed the state map for big premium increases or non-renewals. That has the sound of an easy way to say “we’re not the bad guys—government is.” We’ve referred these rumors to the Oregon insurance commissioner, who follows up with a brief investigation. The results confirm that these companies have no interest in our maps.

This argument has gone on for a couple of years now and probably won’t go away. And it’s really beside the main point that people in hazardous areas have a critical insurance problem. There’s no fast or simple solution. My focus will continue to be improving and investing in effective wildfire prevention programs that will bend the curve of claim pay-outs back down in hopes that premiums will follow suit.

In the coming legislative session, I’ll also be introducing a bill I’ve twice before passed through my Natural Resources and Wildfire Committee (only to have it stuck in the Ways & Means Committee at session’s end) to create a statewide network of fully voluntary ‘Neighborhood Protection Cooperatives.’ This would build on the success of current programs where neighbors collaborate and encourage each other to take simple steps to reduce wildfire danger on their individual properties.

Neighborhoods that complete the risk-reduction tasks laid out by on-the-ground experts would receive a certification that, if pending negotiations go well, would be recognized by the insurance industry with lower premiums than the homeowners would otherwise have to pay. We believe the industry will recognize the very strong interest we share in reducing catastrophic wildfire risk in our communities. Repairing insurance markets will be a steep climb. We have to begin now.

“My property is rated high-hazard while my neighbor’s, which is equally [or more] hazardous, is ‘moderate.’ What gives?”

I got plenty of these two years ago, when the first map came out. I walked a lot of Rogue Valley properties with their owners. Some classifications had a logical (if complex) reason, but others baffled me. The current draft map took care of some of these weird cases by acknowledging the hazard-reducing nature of irrigated lands, but I’m still getting reports that trouble me. Some probably come from misunderstanding the basics of wildfire hazard, but it’s also true that mistakes get made. I’ll help rectify those that I can.

That’s the top line—not a complete list—of current concerns about the new draft map. I want to close with an admission and an appeal.

The admission is that the implementation of SB 762 is not perfect. It may be far from it. The plain fact is that we’ve never been in the place that this decade’s megafires have now put us. Our communities are faced with destruction—we got a more graphic preview of that in 2020 than we really wanted to see—if we don’t take bold and broad steps to create a different path. With every summer renewing the danger, we have to do that quickly, and learn quickly from our mistakes, like the 2022 publication of the first map with almost no public outreach. We’re the textbook case of tuning up the plane’s engine while it’s in the air. Circumstances offer no other way to do this.

The appeal is to everyone who understands how profound the wildfire threat has become; after the 2020 fires that means just about everyone. The stakes are so high, and the climate projections for coming summers are so worrisome that we have to find a way to pull ourselves together. We need less blame and grievance, more trust and grace, all around.

It’s often said that we humans seem able to set aside hostilities and come together in the wake of disaster. The question on the table is whether we can do that before disaster, when we’ve been shown so clearly what that disaster looks like. I think the answer is ‘yes.’

Jeff Golden serves as senator from Oregon State Senate District 3.

Capitol Phone: 503-986-1703

Capitol Address: 900 Court St NE, S-421, Salem, OR, 97301

Email: Sen.JeffGolden@oregonlegislature.gov

Website: https://www.oregonlegislature.gov/golden