Restoring public confidence in military service

5 min read

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

by Marty Wilde

America faces a crisis of confidence in its military. The Army has not hit its recruiting goal in three years. The Navy missed its goal last year and will likely only make this year’s goal by significantly reducing academic standards.

Public confidence in the military’s fidelity to the Constitution is also falling. A recent planning exercise speculated that, if called to put down an insurrection by Trump supporters after a loss later this year, a significant portion of the military would not respond.

Public support for the military has fallen from 75% to 60% since 2018. The next President should refocus on the military participation as serving as part of a team, reverse rising disability rates, and realign defense priorities to match our real world challenges.

Focus on the team. Perhaps the worst recruiting slogan ever was, “An Army of One.” At its core, military service is the subordination of selfish motives to the team’s higher purpose. In a country with a crisis of loneliness, military service provides young adults with the opportunity to work with diverse people in close quarters as part of a close-knit team. Yes, monetary benefits motivate people to some degree, but the Marines, for example, have always focused on being part of an elite team. They hit their recruiting goals much more often than the other services.

It’s not just about recruiting. At its best, the military serves as an example of a collaborative organizational culture. By forging a team of people from different backgrounds, the military shows that we can reach across social and political divisions for the common good. In a time when voters are more likely than ever to characterize the other party as not just misguided, but actually evil, the camaraderie of military service offers an example we can’t afford to lose. This ability to work as a team isn’t just important for society – employers cite the ability to work as a team almost twice as frequently as technical skills as a quality that veterans bring to their workplaces.

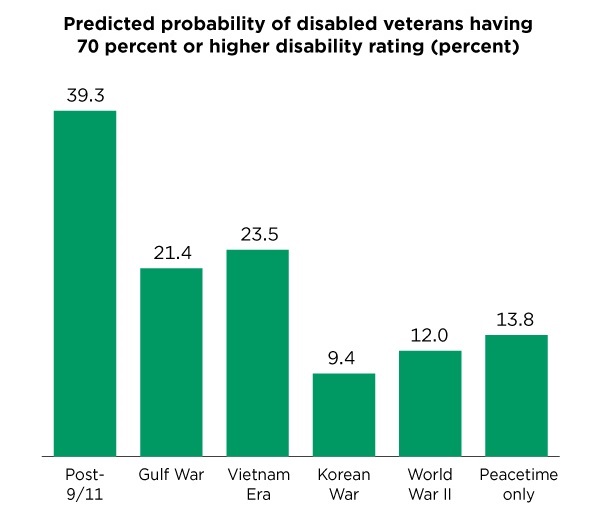

Prevent disabilities. Forty percent of post-9/11 veterans have a disability rating. The most common disabilities are hearing, back, and knee problems. Overwhelmingly, these are not the unavoidable results of combat, but rather the results of failure to train and protect our troops adequately. The military bought defective 3M earplugs for years, leading to one of the largest class action settlements in history for hearing damage to veterans. Back and knee injuries often arise from failing to train troops properly on injury prevention, using human labor when mechanical means would be safer, and insufficient physical conditioning for the stresses of their work. Would you recommend your child take a job that had a 40% risk of permanent disability?

Fixing the problem requires sustained attention. In 28 years of service, I never saw a commander fired for excessive injuries in their unit. When I served in the infantry, the Army did not invest in the kind of hearing protection that filters sound, so troops rarely used their earplugs because they could not hear necessary instructions and communications with them in. Reviewing innumerable files when I worked for the VA, many of the injuries I reviewed were easily preventable.

The military branches have little financial incentive to prevent injuries, as the vast majority of benefits are paid from the VA budget, not the Department of Defense budget. While no commander I ever met wanted their troops to be injured, when it comes to getting a job done faster with higher risk to the troops versus slower at lower risk, commanders knew which choice would be rewarded, even in peacetime. This is a cultural problem we need to solve.

Refocusing the military on the nation’s needs. Flag officers in the military share one common trait – they have all served more than 20 years, primarily in a single career field, and almost universally in a single service. This makes them very experienced, but it makes them very slow to adapt to change. The war in Ukraine has shown the inherent vulnerability of large concentrations of troops and large military machines to attack by drones, but the military services continue to prioritize spending on large manned weapons systems over smaller unmanned ones. Fighter pilots want to buy planes, tankers want to buy tanks, and ship drivers want to buy ships, regardless of whether these are likely to play a significant role in a future conflict. This failure to adapt is plain to see and puts lives at risk unnecessarily.

Even when the military wants to change, Congress often will not allow it to. We continue to carry an excess of unnecessary bases left over from the Cold War, with the most recent comprehensive review determining that 22% of the military’s bases were unnecessary to accomplish the military’s missions. These drain tax dollars away from more pressing military needs, but Congress will not allow the military to close them.

Congress also continues to pay for legacy weapons systems, often without a military need. In an era when a hypersonic missile quite literally cannot be stopped, the Navy would be much better off if we never built another aircraft carrier, and the Air Force has tried to get rid of the aging A-10 for decades. Political interests in the states where we build or field these weapons systems insist on continuing them. Congress should take the opportunity presented by the drawdown of military stocks to support Ukraine to reconsider spending on legacy systems with little relevance to current military priorities.

Our force structure also continues to reflect times gone by. Moving more of our troops into the reserves would allow us to continue to have the same ability to respond to a major war while preserving more of the budget to train our active duty force better. The ratio of troops who actually see combat has rarely been lower, with fully 40% of active duty troops never deploying in an era when much our military has been forward-deployed overseas for the last 23 years. We definitely need gyms to keep our troops fit to perform their missions, but do we really need people in uniform handing out the basketballs there? These “stay-behind” jobs push more of the burden onto fewer troops, leading to burnout and more injuries among them.

Finally, those deployments must be better thought out. I fought in two wars where our political leadership could not define the political goal of our military mission. Our military culture is poorly suited to nation-building, but two of my three deployments were in support of civilian governance. It is not the role of the generals and admirals to define the political end state; it is the President’s. Regardless of party, our Presidents of both parties routinely fail to perform that basic duty of their office. Few things are more demoralizing to the troops than the lack of a defined mission.

Leadership. The crisis of confidence in the U.S. military is fundamentally one of leadership. Given a clear mission, appropriate forces and equipment to perform it, and a political and military culture that supports them, our troops will rarely fail us. As we approach the election, let’s remember that when deciding on the candidates we support in November.

Marty Wilde represented central Lane and Linn counties in the Oregon legislature. For more of his Letters From a Recovering Politician, subscribe at https://martywilde.substack.com/subscribe.