Local officials describe effects of Mosman order

5 min read

Eugene Police Chief Chris Skinner and Lane County Commissioner Pat Farr testified before a state legislative committee Dec. 8. They spoke about the mental and behavioral health crisis on the streets. Commissioner Farr says the current system is ‘about broken.’

[00:00:14] Lane County Commissioner Pat Farr: My name is Pat Farr. I’m the chair of the Board of Lane County Commissioners. As many of you know, Judge Michael Mosman issued a fairly unique order this summer that mandated aid-and-assist defendants be returned to their community under strict timelines, irrespective of whether they have been restored or not.

[00:00:29] Part of the work Judge Mosman did was to ensure that Deborah A. Pinals, a neutral expert from Michigan with expertise at the intersection of the criminal justice system and the mental health system, created recommendations for him. I’ve placed her report in the record.

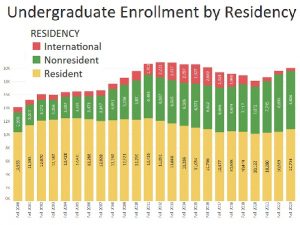

[00:00:43] This shows how many times the defendants she studied have been in and out of the state hospital. This data did not surprise me because much of the information that you see there, our own staff has already testified to the Board of Commissioners on how a person’s mental health illness essentially gets worse with each trauma they experience, including interactions with police, courts, and then with the state hospital.

[00:01:06] What I’d like to suggest to you is that this system is about broken. We need to be examining better ways to initially interact with those who are involved with nuisance-type crimes, have them not all go to jail and not get in front of a judge whose only tool is aid-and-assist orders.

[00:01:21] And here’s my magic wand answer. We need a system that actually gets real treatment for the people, not just treatment to fulfill their obligation to the court. I believe this is our collective challenge: A true partnership with the legislature to evolve programs that give mobile crisis teams a place to take folks in crisis too, with the back door from that facility to continue to help these individuals develop strategies to cope and instill hope.

[00:01:43] We do have ideas on how to evolve a system of behavioral health crisis centers, but we’ll need new statutory frameworks and we hope that you’ll work on those this session. We need to begin that work today. Thank you, chair.

[00:01:54] Eugene Police Chief Chris Skinner: I’m Chris Skinner. I’m the chief of police here in the City of Eugene. As we work to provide a safe community, there are very few places to take people experiencing mental health crisis that require law enforcement intervention.

[00:02:06] The Mosman ruling only exacerbates an already untenable situation. Working with our municipal court judge and city prosecutors, we have identified three key aspects of concern with the Mosman ruling in any legislation that may be happening to come forward.

[00:02:20] First, differentiating between misdemeanor and felony charges for purposes of triage access to care decreases public safety in Eugene. If we must triage these individuals, we really want to be looking at who is an immediate public safety concern and who is a safety risk to themselves or others.

[00:02:37] And as you can imagine, prioritizing a Class C property crime is different than someone with several misdemeanor assaults. In fact, many of our most severely mentally ill people are actually not violent felons here in the City of Eugene.

[00:02:52] Second, the Mosman order has compelled the city prosecutor’s office to dismiss numerous multiple incident and violent crime cases because there’s no viable path forward to secure the conviction.

[00:03:03] The City Prosecutor’s Office already makes a significant triage based decision on what cases to press forward and after the aid and assist issues are raised. The Mosman Order exacerbates this issue.

[00:03:14] Based on the effects of the Mosman order, the City Prosecutor Office sees no path forward but dismissal of many of these cases and defendants are not held accountable, victims of crime did not experience the justice they deserve, and many individuals who are unfit and have a significant amount of criminal history and significant number of pending cases simply don’t have the ability to be restored within 90 days. Some of our defendants returned from the state hospital, timing out under Mosman order, still unfit, still a danger, and end up on the Eugene streets.

[00:03:46] Lastly, restoration in the community is not a reality under the current statutory framework and unlikely given current resource allocation in the Eugene / Lane County community. It cannot be stressed enough how much community restoration fails to achieve the goals of all the stakeholders. Defendants easily miss their court requirements, are placed in warrant status, and disappear.

[00:04:07] Outpatient contact with local mental health provider is limited and yielded very few, if any successful restorations within the community. These cases struggle to find any kind of resolution and are usually only addressed once the individual accumulates additional criminal charges and is held in custody.

[00:04:23] This denies equitable outcomes for victims and creates a sense of helplessness in the community by the citizenry.

[00:04:30] This revolving door of people offending, being held, released, and re-offending is taking a toll on our community and many of my officers. Without state investment in mental and behavioral health system improvements, we will continue to see our numbers of mentally ill people grow on our streets.

[00:04:43] Alex Cuyler: For the record, I’m Alex Cuyler. I’m Lane County’s intergovernmental relations manager. I’ve been working on an issue and it’s what I refer to as risk-shifting that has occurred concurrently with the buildout of community-based treatments. So risk-shifting occurs when policy is evolved that exposes local government to risk that previously had been covered either by the state or through systems that had already been insulated via immunity provisions under Oregon law.

[00:05:09] Defendants previously were treated behind the four walls of the Oregon State Hospital, but now, treated in the community and clearly any actions that they might undertake that can be criminal in nature or impactful for others were the responsibility of the state when they were at the state hospital. Now they’re in a community setting. Their behaviors haven’t necessarily changed, but their inherent risk portfolio has shifted to local government.

[00:05:36] We feel the overall system is more fragile as a result in that costly litigation could easily arise that may cause county decision makers to question the sustainability of such service delivery.

[00:05:48] And there are a variety of risk mitigation steps that we’d like to see in statute to, to help prevent incidents that could result in litigation. 2015, Lane County had a person who was ordered into treatment by a court. That person ended up being involved with the deaths of three individuals. Their estate is suing us for $27 million in federal court.

[00:06:13] A judgment like that would probably cause the county to really take a hard look at its ability to continue to provide these services. And so disruptions like that litigation to this system, which depend on county mental health programs and a great many players who revolve around these defendants, could easily collapse.

[00:06:35] John Q: Officials from Eugene and Lane County tell legislators: Here’s what state policies and court rulings look like on our streets.