Dan Bryant describes ‘Village Model’ for affordable housing

7 min read

Dan Bryant described the 'Village Model' for developing affordable housing.

A city-county Town Hall on June 3 addressed homelessness, health, and human services.

City Councilor Claire Syrett: [00:00:08] I really appreciate this joint town hall bringing different aspects of our local government together because many of the things that we want to accomplish, we need to do together rather than working in silos or being territorial about where our jurisdictions lie. Homelessness is definitely one of those. Transportation is another and Human Services, which goes beyond addressing the needs of folks who are unhoused, is another important aspect…. The rest stop program, Opportunity Village—I think those were both the beginning of the City of Eugene really recognizing that we needed to be more hands-on in addressing the needs of our unhoused residents.

Presenter: [00:00:53] For more details on Opportunity Village, we turn to Dan Bryant and Dan Hill, speaking at a Friendly neighborhood meeting this spring.

Dan Bryant: [00:01:02] I’m a preacher by trade, but got involved in this non-profit effort to build a new style of housing. We started our nonprofit Square One Villages back in 2012 and built our first project, Opportunity Village Eugene, in 2013. I like to call it a gated community for the homeless. Built it over nine months with a lot of volunteers, a lot of donations of labor as well as materials. And it became , I think, a very attractive little community for about 30 to 35 people where the average length of stay is somewhere between 12 to 18 months until people are able to move out into other housing.

30 units in all of bungalows and Conestogas, these are just simply detached bedrooms up until this year had no electricity. We now have solar power on 20 of them, and we’ll be adding electricity for the remaining 10 so that everyone at least has heat during the winter. And then they have a shared bath house and a kitchen and pantries with cooking utensils and outdoor cooking area.

Thank you for supporting

local civic journalism

But our biggest problem was we had, was helping the villagers to transition out to find affordable housing. And so we discovered we had a significant number that were ready, they had income, they just couldn’t find housing. And at that time Homes For Good, what was then called HACSA, published the wait times to get into those various complexes . And I was rather stunned when I looked at that and discovered that wait time for a three bedroom apartment was about one year. This is for the units in the Eugene area for two to four bedrooms. It was two to three years, but for a single bedroom or a studio apartment even, the smallest they had, something for a single individual or a couple, the wait time was over six years.

And that’s when we decided as a nonprofit that we needed to get into the business of building our own affordable housing using this village model that we had developed as a transitional shelter for the homeless. And so our first project, Emerald Village Eugene, off of the railroad and Polk in the Whiteaker community, that’s an acre of land that we bought in 2015 through fundraising.

Unlike most affordable housing projects, the residents of Emerald Village are not simply renters. They actually own the co-op that leases the facility from the nonprofit. And they have a share value. So their share value in this case, this is a leasehold co-op is $1,500. So they have an asset, a very modest asset but more importantly, they have an ownership stake in their housing, and therefore they’re more apt to take responsibility for it.

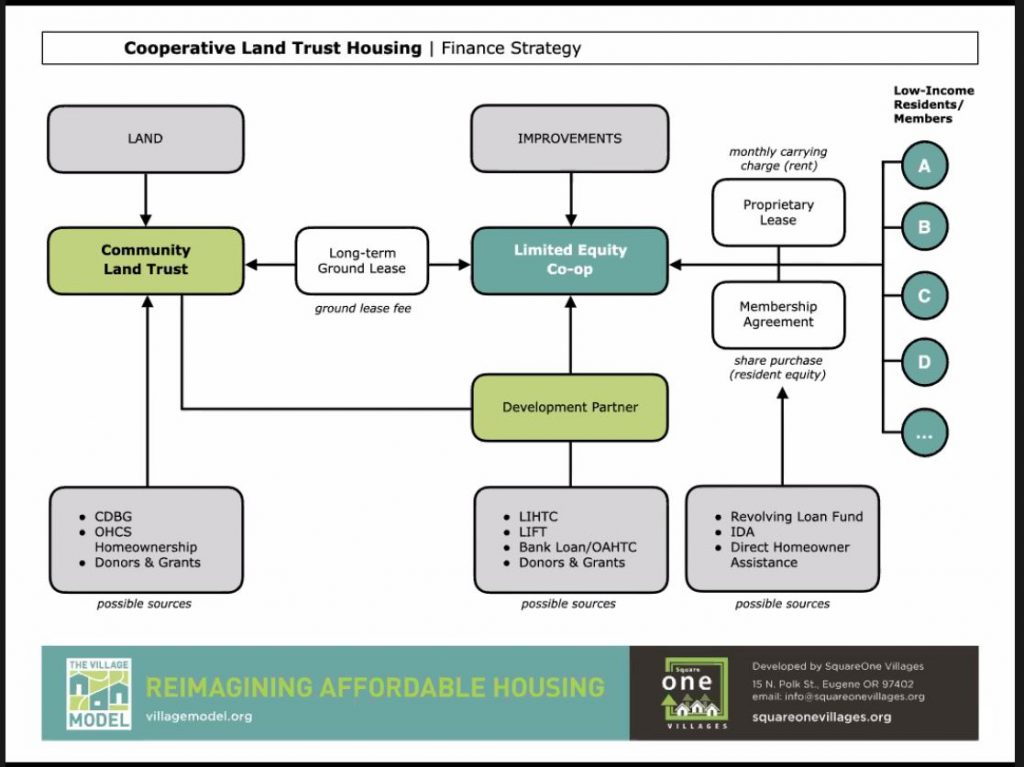

We call this our “Village Model.” Technically it’s a combination of a limited equity co-op with a community land trust. Housing co-ops are not particularly new. They’ve been around for a long time, especially on the east coast where apartment buildings have been converted to co-ops. The difference between a co-op and a condominium is, in a condominium, you own your actual unit, and a co-op you own a piece of everyone’s unit. So if there are 50 units, you own 1/50th of your unit and 1/50th of everyone else’s unit. So they tend to be very democratic in the way that they’re run.

So the difference in what we’re doing is we combine this with a community land trust that owns the land. And that way the co-op has a ground lease with the community land trust, the community land trust stewards the property, and basically ensures that it remains affordable in perpetuity. And there is by the structure of the ground lease and the bylaws. So the co-op members they can’t sell it at market. They can sell it to another person at a predefined rate of appreciation, so to protect their investment. But they’re not going to get a huge gain because otherwise it will no longer be affordable if you allow it just to rise with the market.

And so you take the cost of the land out of the housing equation. So that saves you some money. And then the co-op only pays for their housing. So a couple of big benefits to the structure: It’s resident-owned housing, and that is usually preferable to rental for several reasons for the resident, it increases their financial stability. It gives them that residence asset to the property and therefore they’re much more likely to take care of it and it allows them to build equity and it gives them more control over their housing.

It is up to the co-op to raise the price, not the community land trust. If they can’t meet their budget, then they have to decide, are we going to cut expenses or are we going to raise the cost of the lease in order to manage this? And they also share in the management task. There’s no landlord—they are the landlord. And so they formed committees to share in the management tasks of running the co-op.

And we’d like to say, We’re not just building housing, we are building, right, a village, we are building community and there’s just absolutely something wonderful, magical that happens, when you hand over that key to a new resident who never dreamed of having their own home. And especially when you develop a relationship between that resident and the builder and they get to know one each other, and there’s a, a really deep connection there. That’s just a powerful thing to experience.

We couldn’t have done this project without all of these folks like Dan Hill and the other architects. The in-kind donation from these builders and the architects was nearly a half a million dollars. And that’s was really key to making this project affordable.

Presenter: [00:06:31] Dan Hill said the high costs of infrastructure, connecting to water and power, can still be a barrier.

Dan Hill: [00:06:38] The largest challenge for any meaningful addition of housing to existing neighborhoods is related to infrastructure costs. A lot of times we’ll have really wonderful sites but what we find is the infrastructure, and that means your sewer, your water, your power, your natural gas a lot of times are very difficult to actually get to the site, and the costs are quite extreme.

The other challenges that we see are on the fee structure side at the last calculation of what we call soft costs, which are your design permits, engineering planning fees. Those are running in the 25% range right now. And so those are adding significant numbers to the cost of our housing.

And then obviously this is a big one, the challenge of neighborhood resistance. And these sometimes are some of the largest challenges that we have because people don’t like change or they don’t want to see that kind of change in their neighborhoods. Neighborhoods that have resources can sometimes mount legal battles against development that they really don’t want in their neighborhood.

So these are the three big ones that we see as developers and looking at ways to increase our housing stock. Many years ago I was very active and I was still am very active in the Home Builders Association of Lane County. And we foretold what was actually happening right now that with our land supply being so restricted, that housing costs would go up in a dramatic way and as we look at housing cost, they’re pretty much out of the reach of about, I’m going to say 60% of our population. So that increases demand for rental housing.

And a lot of that rental housing is in older homes. Many Like in your neighborhood that were built back in the thirties, forties and fifties, some even earlier than that. And so that housing stock is getting more limited. And part of the reason it’s getting limited is because people are going in and gentrifying neighborhoods they’re taking the route of creating new housing by possibly tearing down some of the old housing. And of course, anytime you do that, the price of housing goes up. That new housing is more expensive than the old housing that was on that property. So as we look at what’s happened over the last 25 years in Eugene, we haven’t paid really good attention to our housing needs and more and more people are being pushed out of the opportunity to actually have home ownership.