Eugene activist: Help me protect Thacker Pass

9 min read

Eugene activist Max Wilbert invites you to join him near the Oregon-Nevada border to protect Thacker Pass.

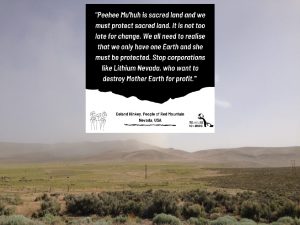

Eugene activist Max Wilbert has started occupying the site of a proposed lithium mine along the Oregon border, which the Trump administration approved just five days before leaving office. Max was interviewed by KEPW’s DJ Suss D for Talk Is Cheap, which airs Saturdays at 4 p.m.

Max Wilbert: We’re in northern Nevada, which is part of the northern Great Basin. The Sagebrush Ocean. There are something like 44 mountain ranges in Nevada and between them are these broad flat valleys. And, the mountains get pretty high. There’s a 9,700 foot peak just to the east of us here. This is traditional territory of the Northern Paiute and the Western Shoshone nations.

Thacker Pass is this broad saddle between these two mountain ranges, and it’s very ecologically important. Humans use a pass to go over a mountain range. You go over McKenzie Pass or Willamette Pass, Santiam Pass. This has been a highway, not just for indigenous peoples, but for wildlife. It’s the best and easiest way to get from the Montana Mountains just north of here to the Double H Mountains to the south of us. It’s an important migratory corridor for pronghorn antelope, the only antelope species in North America. It’s habitat for the greater sage-grouse, whose population has crashed significantly since colonization. It’s dropped by about 97 to 99 percent from its historic numbers. And this area of Thacker Pass and the surrounding regions is the best sage-grouse habitat left in Nevada. There’s nesting golden eagles. There’s all kinds of wildlife.

Thank you for supporting

local civic journalism

This issue is so important right now because with the new administration, we’re seeing the push towards electric vehicles, towards more wind and solar energy production. Those require electric batteries. So the lithium industry is poised to explode around the world. And we’re rushing into this blind. So many people think that these technologies are completely benign, that there are no problems with them. This idea of lithium, this idea of solar and wind as being the technologies that will save the day magically. I think those are lies. Almost all of the raw materials from these, for the technologies come from open pit strip mines, mountaintop removal mines, just like we see in Appalachia.

The indigenous communities in Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, up on the salt flat regions of these countries where the lithium mining takes place, are very upset. There’ve been human rights violations. There’s devastation. And the story’s the same in Tibet. There’ve been cases of lithium mines poisoning rivers, dispossessing entire communities in these very rural areas that rely on agriculture, rely on producing food from the land to sustain themselves.

The disturbance footprint of this mine is about 5,700 acres. That’s the land that will actually be bulldozed. But that doesn’t include all the indirect effect to the surrounding areas. The project site itself is over 10,000 acres in size and it includes some quote unquote exploration areas that could triple the size of the disturbance footprint in the future.

For those who don’t know what a 10,000 acres or 20,000 acres looks like, the open pit mine proposed for this area is about 2.3 miles long and half a mile wide. If you were at the the Fred Meyer in West Eugene and you’d dug an open pit, a stretch from there to the Kiva, right in the middle of downtown Eugene or the bus station, and it was half a mile wide and 400 feet deep, so maybe it stretched from 11th down to 18th, maybe a little bit further south than that, and you dug a hole 400 feet deep there, that’s the kind of area that we’re talking about. And this isn’t an urbanized area, this is wildlife habitat. This is critical habitat for all kinds of species.

And then there are the indirect impacts. They’re blowing this place up using explosives, they’re running heavy equipment, 24 hours a day. They have spotlights on all the time. They have a sulfuric acid plant on site, which literally is bringing sulfur in from oil refineries . It’s not separate from the fossil fuel economy. It’s tied into it. They’ll be burning more than 11,000 gallons of diesel fuel per day on the site. And there are a lot of species that even if their home isn’t directly bulldozed, they won’t tolerate that. They don’t want to be anywhere near something like that.

The project plans to pump something like 1.7 billion gallons of water per year out of Nevada, the driest state in the country. Already the groundwater aquifers in this area are overdrawn every year. There’s issues with groundwater pollution, there’s uranium, arsenic, antimony in the soil. Those things are pretty much locked up in the rock and are safe for now. But when you bulldoze all that, when you explode the soil, you put in your dynamite and you blow it up, and then you process that soil and you extract the lithium and then pile all the waste rock in a giant mountain, all those harmful and dangerous minerals and elements can be released into the groundwater. They can be released as dust. They can blow all over the landscape and into the surrounding communities, down into the agricultural zones and onto the crops that, that people, animals are relying on. Beyond the direct material impact, there’s a massive impact that’s indirect.

We’ve all been sold on this idea that wind and solar are these magical technologies. And we’ve all seen the commercials for the electric cars, happy family, driving through a beautiful forest with clean air and nice quiet music playing in the background. And the advertising tells you, it programs you, right? This is the kind of future we should have, but that’s not what a green future looks like. That’s a dystopian future that’s being sold as green. The problems are a lot more deeper than that. We can’t just change what’s under the hood of the car, in the gas tank of the car and expect everything to be okay. We can’t just switch the fuel source for our cars or more broadly for capitalism and expect the planet to be saved, because we live in this culture of over-consumption, of energy addiction, of perpetual growth and no matter what the energy source is, no matter what the fuel is, that culture will destroy the planet regardless. The culture of domination, a culture of profit and accumulation that’s not based on relationship, that’s based on brutality. And that’s what we have to get away from. Jack Forbes indigenous writer called it the Wetiko sickness, psychological disease that causes people to just want more and more.

We’re entering this new era of extreme climate change. The sixth mass extinction, ecological collapse across the planet, the oceans collapsing, insect populations collapsing, songbird populations collapsing, amphibians across the board. Our children are not going to have a future unless we figure out a better way to live.

And so we need to be having those conversations about, what does a real transformation look like and what kind of world do we want in the future? I think we need to change our priorities as a society and address these problems directly rather than trying to rely on the free market and technological innovation and private corporations to solve the problems for us. They’re largely that the ones who got us into this mess, and I don’t think they’re going to get us out of it.

We need to protect the natural world. We need to actually stop the destruction. The thing about intact habitat, is, it provides clean water, it provides building materials. It provides materials to make clothing. It provides food. It provides medicine, it provides the necessities of human life. And none of that is provided after you’ve blown up a mountain after you’ve poisoned a mountain after you’ve taken all the water and filled it with sulfuric acid and uranium and left a mess that will be there for who knows how many hundreds or thousands of years after the fact.

So that means we need to stop pumping oil. We need to stop logging the forests. We need to stop overfishing the ocean. We need to stop with this industrial agriculture paradigm that relies on bulldozing and then, planting one crop, as far as the eye can see and just bathing it in pesticides and fertilizers. We need to do things in a different way. That’s where a real solution lies. That’s where we can start to reverse the ecological crisis that we find ourselves in.

And I think as a society, we need to figure out a better way. We need to use less. Our grandparents lived through the Depression and they lived through a period when they had to restrict their lifestyles and to restrict their consumption because of the circumstances they found themselves in.

I think that we need to make do, with a lot less. We need to localize our societies. People talk about local food movements and, trying to eat within a hundred mile radius of where you live, “food shed” or something of that nature. How about we talk about 100-mile technologies, right? How about we talk about, You don’t get to use a technology unless all of its components come from your direct area, your technology watershed, or what have you.

And in many cases, I think that will actually improve our quality of life. You have to actually have a relationship with the soil that produces your food. You have to actually have some sort of relationship with the springs and the rivers that create your water. Because, you’re getting what you need to survive from the land around you. Not as some sort of a rugged individualist, but as a community, figuring these things out together. All of these things are not technically difficult, but what we need, the hard part, is the political will, the social will to change our society, and I think that requires getting organized. That requires building organizational structures, becoming part of different groups and taking political action that advocates for these things at the city level, the county level, the state level and beyond, and starts to, move funds and resources from our governments into these sort of re-localization projects.

We shouldn’t be subsidizing electric cars and lithium. We should be subsidizing salmon restoration in the Willamette and taking down the dams because that’s a food source. That’s a source of life and vitality that has existed for millions of years and could support humans for millions more.

I recognize that I’m talking about a fundamental transformation in our society, but that’s the work of our time. That’s what we’re here to do. We’re living in this existential moment for the human species. And the question is, Do we have the courage? Do we have the strength? Do we have the capacity to do these things?

My experience has been, being involved in this political struggle is the best thing that ever happened to me . You can’t ask for more meaningful work to do with your life. I hope people will try and find purpose in this and, set aside all the excuses and the self limitations that you’ve been clinging onto for so many years. It’s time for us all to step up.

We really need people to come out to Thacker Pass, to be on the ground, to engage in direct action and protest and be ready to stand against the machines when they show up to destroy this place. I think we need to force a moral reckoning around these issues and that will require a lot more people joining us. We have information about what’s needed at camp, and we would really love to have some more folks from the Eugene area out to be part of this.

It is incredibly beautiful out here. If you love the wild, if you love the natural world and the beauty , it’s just almost unbelievable. So I really recommend that people come out to the site. You will fall in love and once you fall in love you’re accountable, you’re part of something, you’re part of a family. And you have to do something to protect your family. And so I hope you’ll come out here and become kin and become kindred with Thacker Pass.